Op-Eds do not reflect the editorial opinion of The Daily Free Press. They are solely the opinion of the author(s).

Jillian Napolitano is a senior in the Boston University College of Communication.

Stan culture, which describes a community of over-excited fans, was first coined in 2000 but reached a whole new level under the rise of social media later that decade.

People born between 1996 and 2000 were the first to grow up on social media during their most formative adolescent years. So, stan culture has mostly affected students who either recently graduated college or are currently attending.

Growing up with the internet imposes long-lasting effects on one’s psychological thought process, especially for people like myself, who developed a social media addiction to help cope with a severe depression.

In the years 2013-2017, I witnessed Twitter’s overhaul by teenagers — mostly female or part of the LGBTQ+ community — seeking an outlet for their emotional trauma. They were able to find connections through its fandom communities.

People were put into sections, or chambers, that allowed a small community to be built out of the internet’s vast scope. Each chamber echoes the same information, which influences a small section of the world’s personality.

These chambers allow unhealthy trauma and coping mechanisms to reverberate across the fandom and its culture because they are so intertwined, teaching young children incorrect ways to cope.

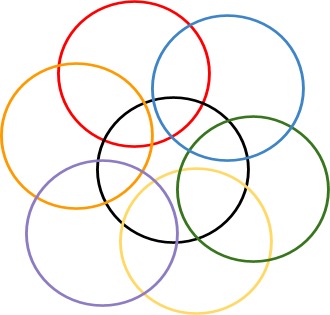

Fandom culture is easily explained through overlapping circles. Normally, one fandom gets someone to join a social media app, which can be represented by a black circle. But as time continues, the black circle is accompanied by all the colors of the rainbow, or at least the colors that are shown by fellow users. The world has millions of colors, but the colors you see are decided by the algorithm that powers social media apps.

For example, think of the TikTok algorithm like a map. The internet puts users into groups based on their interests, which have been tracked over time. The longer you stay on an app, the more information it has about you.

These groups put you in different subsections of the internet, all of which see similar media content from the app. This creates the echo chamber idea — people get stuck in their section of the internet and do not hear from other sources, which contributes to the world’s current issue: we no longer have a basic level of truth because every subsection of the internet has different understandings of basic facts.

These groupings and echo chambers can be positive in many respects, but they can also be negative, specifically when discussing mental health among teenage users. If you have joined a community that fosters healthy communication, self-growth is inevitable. However, if you join a community that has unhealthy communication skills and terrible coping mechanisms, you are left in a completely different arena.

These social media chambers can be positive or negative. You will always have company on your journey, but certain parts of the internet promote unhealthy lifestyles that have caused the rise in mental illness in our youth.

Students at Boston University, we are the ones most affected by social media growing up. We experienced the emotional ride of puberty with Silicon Valley designing the track.

To properly address the rise of mental illness in teens, it is integral to educate the entire population on the true effects of spending all our time on social media.

But this first starts with informing the people who were the first effective targets of this phenomenon. Those directly affected — everyone in our age demographic — have the right to know these social media companies used us as a product to make money, and they still do.

Others like me need to know that an algorithm notices when users see something and engage with it, so similar content will continue to show up on their feed. Twitter, for example, does this so it can get more engagement and accrue more money, which allows the platform to sell advertisements at a higher rate.

The information you’re seeing online is curated for you. The posts you see are not a sign from the universe that you deserve the pain you are going through. You are not a burden. You are not alone. You are not too far gone.

Please, keep fighting, and keep trying. After a severe four-year battle with mental health, which I’m still trying to recover from, it’s not easy. I’m not happy all the time. But it finally feels like I can see the sun again.