In 1980s New York, a new stream of thought known as “Zulu Nation” emerged, preaching hip-hop principles that graffiti legend George “SEN-1” Morillo lives by.

These elements — DJing, MCing, breakdancing, graffiti and knowledge — led the path for young teenagers in the ’80s and SEN-1 eventually propelled to a global stage.

Ducking from outlaw gangs and taking note of territory, SEN-1 said as a kid, he lived every day as if it was his last. In doing so, he said he became foundational to a scene that was an escape from the city. The important elements of his life that became a part of his identity.

“It was really important for us to know who we was, what had happened to us in history, and how we was going to unify and try to reclaim our identity through all of this,” SEN-1 said. “It was like a cultural revolution.”

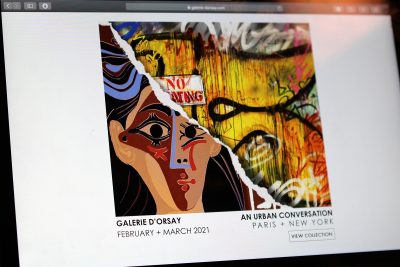

Now, after transitioning into the fine-art world in 2009, SEN-1’s pieces are being presented at the Galerie d’Orsay in Boston’s Back Bay.

The exhibit, “An Urban Conversation Paris + New York” will be up throughout February and March. SEN-1’s work will stand alongside 10 other artists, including works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse and Alexander Calder.

SEN-1 said he has been working with Galerie D’Orsay for three years. He first made contact with the galleries during a trip to Boston, when he visited upwards of 20 galleries.

“I decided I was going to check out every single one of those galleries,” he said. “I literally just went down the entire strip and stopped at every single one.”

Galerie d’Orsay was his first stop, he said.

“The energy was just incredible,” he said. “I walked in there and it was amazing.”

After seeing how many contemporary artists were emulating his work, SEN-1 put pressure on himself to prove he was the “father of the style” — an energy Martha Folsom, co-director of the Galerie D’Orsay, took note of.

“There was something about SEN-1 when he came in,” Folsom said. “There was a uniqueness and an authenticity to his work and there was a story that was just so amazing to me.”

Every year, the gallery picks one to two artists to display, Folsom said. She said she “immediately” felt his work would be a perfect fit.

Ben Flythe, the fine art consultant at Galerie d’Orsay, said each applicant must be able to show why they deserve to have their work hung up next to the greats.

“One of the things we ask all our contemporary artists is ‘Do you see your art hanging on the wall next to Chagall, next to Miró, next to Calder?’” Flythe said. “If the answer is ‘100 percent truly yes I do,’ that’s a very important thing to ask yourself.”

The goal at Galerie d’Orsay is for the customer to find pieces by the masters and bring them home with them.

Folsom said though the new direction has been more contemporary, it is still essential for the works to complement the greats. She said he thinks that’s exactly what SEN-1’s work is doing.

“His works are holding his own,” she said. “They have the strength, the boldness, but they’re side-by-side by some of the all-time artists that have ever lived in the history books.”

SEN-1 said his works drew heavily from his childhood, growing up in New York and not feeling protected by the system.

“We was a generation that was just wiped off,” he said. “After the heroin epidemic, the system didn’t know what to do with us.”

What ended up being a form of protest birthed a movement. However, the origins of this art style came from the notion of not wanting to be forgotten.

“The reason graffiti was really important to us, it wasn’t about just tagging or doing some art,” SEN-1 said. “It was about leaving an impression that we were here.”

He said his early work with graffiti on subway cars was an outlet and the reason why the risks and the pieces themselves were big, and important.

“If I’m going to be dead tomorrow you’re going to know that I was here,” SEN-1 said. “The risk didn’t matter because the whole idea was I’m going to leave my name really big so that you never forget me.”

Eventually, SEN-1 and his friends were “the kids that nobody wanted around, to all of the sudden, the kids that everybody wanted around.”

When thinking of memories of the past, SEN-1 even recalled the times he partied with Madonna and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

SEN-1 said he appreciates the culture he helped create, and wants his art to share “what hip-hop really was at the time” and how it helped his generation survive.

“My goal was not about elevating myself,” he said, “it was always my motivation to elevate that era of the culture that’s been erased.”

SEN-1 said his love for New York City, where he still lives today, and its culture remain everlasting, and he hopes this exhibit can help share the power of hip-hop.

“The city was a dark place, hip-hop became the light,” SEN-1 said. “We created so much for the world.”

A major theme of the exhibit is that art can be revolutionized and stir up conversation.

Flythe said the sentiments in SEN-1’s graffiti work parallel the anti-establishment ethos of the revolutionary art of the greats such as Picasso, and is a great example of art reflecting culture.

“Art builds up movement after movement after movement, and year after year after year,” Flythe said, “the same way that graffiti builds up on a wall.”

Olivia Hammond • Feb 19, 2021 at 12:51 am

Wow, great article. Something that really blew me away is how his need to not be forgotten birthed such amazing ambition. It’s incredible how his authenticity and passion drove him to such great success, especially since graffiti art has been so often overlooked in the world of “fine arts.” His boldness really does show in his work, and it seems like I can feel his personality oozing through the paint. Very cool to see Sen-1’s work in such a high end gallery, next to artists that we already recognize as masters of their craft. The article is very well written too, kudos to the author for framing him in such a dynamic way.

Youssef khalifeh • Feb 18, 2021 at 10:55 pm

This is a great article Ramsey. We should encourage artists to always bring the new in themselves. The masters did it in the era and Sen-1 is a trail blazer in the graffiti world.