Last Friday, I received a direct message on Instagram from a stranger. My account is private and I haven’t posted since my high school graduation, so this was odd. I almost refused to check it — assuming that it was spam — but on a whim, I opened the message anyway.

“Hey, I’m Sergeant [name] with the Marine Corps. What games you competitive with?” the message said. I checked the user’s profile, and they were the real deal: a military recruiter assigned to my hometown outside Philadelphia.

They saw the phrase “competitive gaming aficionado” in my Instagram bio and instantly pounced on the recruitment opportunity.

I rejected their request on ideological grounds: I’m an active member of Boston University’s Young Democratic Socialists of America and thus abhor the United States’ imperial exploits. I had no interest in hearing the sergeant out.

But unlike my interest in esports, my YDS membership is not as visible on my Instagram profile, so I can see why they thought I was a potential candidate for recruitment.

The most interesting part of the interaction was that they tried using my interest in video games as an entry point. I am already attending BU, so I understand why the sergeant didn’t offer me a college education, but they still could have promised career prospects, medical insurance or the stereotypical Camaro.

After thinking about this online encounter more, I started to realize my experience was part of a larger shift in the military’s recruiting strategy within the past few years.

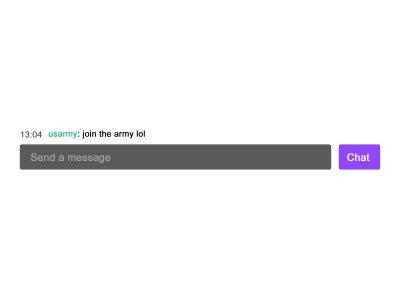

Last summer, controversy swirled around the U.S. Army’s newfound presence on Twitch, a website where people livestream themselves playing video games and interact with viewers through a chat room.

“Instead of approaching a recruiter behind a table in a school cafeteria, kids can hang out with one who is playing their favorite video games and replying to their chat messages for hours on end,” wrote activist Jordan Uhl in The Nation last July.

The Army’s entry into the esports scene followed their failure to meet recruiting quotas in 2018 — their first major yearly recruiting failure since 2005. Their ongoing attempt to increase recruitment through gaming communities is highly predatory and misleading.

Militarized first-person shooter games such as Call of Duty were a fixture in the Army’s streams. These games are not necessarily immoral, but in the context of Army recruitment, they seem even more propagandistic as gamifications of war. Likewise, the Navy’s bio on Twitch used to read, “Other people will tell you not to stay up all night looking at a screen. We’ll pay you to do it.”

Every second of an Army livestream seems to trivialize the prospect of death. Last September, a Navy stream of the game Among Us featured players who named their characters “Nagasaki” and “Japan 1945,” mocking the nuclear incineration of Japanese civilians at the end of World War II.

Army chat rooms were then promptly censored. The mere mention of war crimes was grounds for a ban from the channel, a practice condemned by Columbia University’s Knight First Amendment Institute as a constitutional violation.

It is no secret the U.S. military has a long history of predatory and biased recruiting practices. The term “poverty draft” has been coined to describe the phenomenon: For people with low income and few economic opportunities, the benefits of military service are one of the only paths to upward mobility.

Studies have shown that recruiters appear much more often at poorer high schools than richer ones. The friendly Instagram recruiter’s pitch of financial stability and even citizenship through service is meant to appeal to underprivileged youth. But they conveniently omit that the military has high rates of sexual trauma and suicide and how those actively serving endure frequent violence.

As we speak, esports is being used to transition away from the inadequacies of older recruiting methods and depict war as an adventure without consequence rather than a campaign of violence. Old methods of deception are colliding with new kinds, from the gun use of the first-person shooter to recruitment disguised as giveaways for gaming accessories.

It is tempting to believe gaming is an apolitical escape from the real world, but the Army’s involvement suggests otherwise. Through Twitch streams and sponsorships, the money and playerbase of esports are now being used to power the U.S. war machine. We must oppose this at every step, lest we be complicit in a process that kills the most vulnerable on both sides of the battlefield.

Julie • May 13, 2021 at 12:47 am

I can understand why you would think that the sergeant was attempting to enlist you because of video games, but I don’t think that was his/her aim. I was a recruiter and the first thing you’re supposed to do is establish rapport with the person you’re talking to. I have used video games, specifically a PC Star Wars game, to find common ground with the high school kids I was talking to. To put this in perspective, the sergeant is most likely 23-27 years old. They’re far enough removed from the high school scene and have had enough real-world experiences that they find it hard to relate to a 17-18 year old high school senior. The military ages you in a way you’re not prepared for. Couple that with being told that you have to stop doing the job you enlisted to do (Combat Engineer in my story) and now you have to go talk to kids that will most likely be rude and not listen to what you have to say, makes it extremely difficult to be a recruiter. This is a secondary job that you have to learn how to do in a 2 month school. No one joins the military, especially the Marines, to be a recruiter.

Steven Chach • May 12, 2021 at 8:00 pm

I am frankly disappointed in such a esteemed student news outlet for allowing such a poorly written and biased “article” to be branded with its name. Nothing stated in this article is based in fact, and the “source” of your statement that the military recruits more in poorer schools is another baseless rambling article that sites more “studies” to support their biased ideals. This kind of sediment belongs in the depths of a QAnon or 4 Chan forum, not the Daily Free Press.