On August 25th, a man tried to kidnap a Boston University student at gunpoint from her apartment, which is located near campus. The victim was able to escape — the police arrived after the victim was able to grab the gun and go.

He also brought a tank of gas that could be used to sedate people and a marriage certificate with the victim’s name on it.

This incident is not an example of something horrific almost happening. Something horrific already happened.

The man had been stalking the victim for years before the attempted kidnapping. He grew up near the victim in California, as he’d gone to the same middle school as her friends. He proceeded to stalk her online, as well as send her disturbing text messages and a package.

The news station WCVB found records detailing this man’s frightening behavior leading up to this attack, corroborated by the victim and sources close to her.

But these kinds of incidents of stalking and harassment are not taken seriously by Massachusetts law.

First of all, you can only obtain a restraining order — also known as a 209A order — against a “substantial” partner or ex-partner, a present or ex household member, a parent of a child who is a minor and a relative by blood or marriage. This definition excludes dangerous people you may never have substantial interaction with but may pose a real and viable threat to you.

Second, there is an immense burden of proof the victim must provide to be taken seriously by the court. According to Attorney James M. Lynch, the victim, or plaintiff, in a 209A case must prove by a “preponderance of the evidence” that they have an “objectively reasonable fear of imminent serious bodily harm.”

The “preponderance of evidence” clause basically means that the plaintiff must prove there is more than a 50% chance their claim is true. But the plaintiff, in many cases, must prove their claim at least two times — first, to obtain an emergency order against the defendant with the defendant absent, and second, at a hearing with the defendant present to defend themselves.

Once a restraining order is achieved, it only lasts for a year or less. The Court is then required to review the hearing annually, though sometimes these hearings are scheduled at closer intervals, where the plaintiff must present this evidence again. Only after the first annual extension hearing can the plaintiff ask for a permanent 209A order, but this requires more extensive burdens of proof.

Massachusetts law does consider cyberstalking to be punishable by prison time.

But the burden of proof the victim must provide to be taken seriously, as well as the notorious slow nature of the criminal justice system in regards to these kinds of cases, make these kinds of claims difficult to be treated seriously by law enforcement officials.

Even if everything goes smoothly with restraining order hearings, there are gaps in the system which leave the victim open to potential abuse and violence. Though the court can order to remove the defendant’s firearms, the defendant has the right to petition the judge to reconsider.

The complicated, burdensome elements of restraining orders aside, the lack of active action from law enforcement officials also poses a huge obstacle for victims to obtain proper legal protections from their abusers.

A 2019 investigation from the Atlantic found an “epidemic of disbelief” in police departments, revealing a system in which cops are more likely to think victims of sexual assault and harassment are lying.

These cracks in the system may let potential warning signs fly under the radar of local authorities, both in regards to the lack of clear legal recourse and lack of active effort from law enforcement.

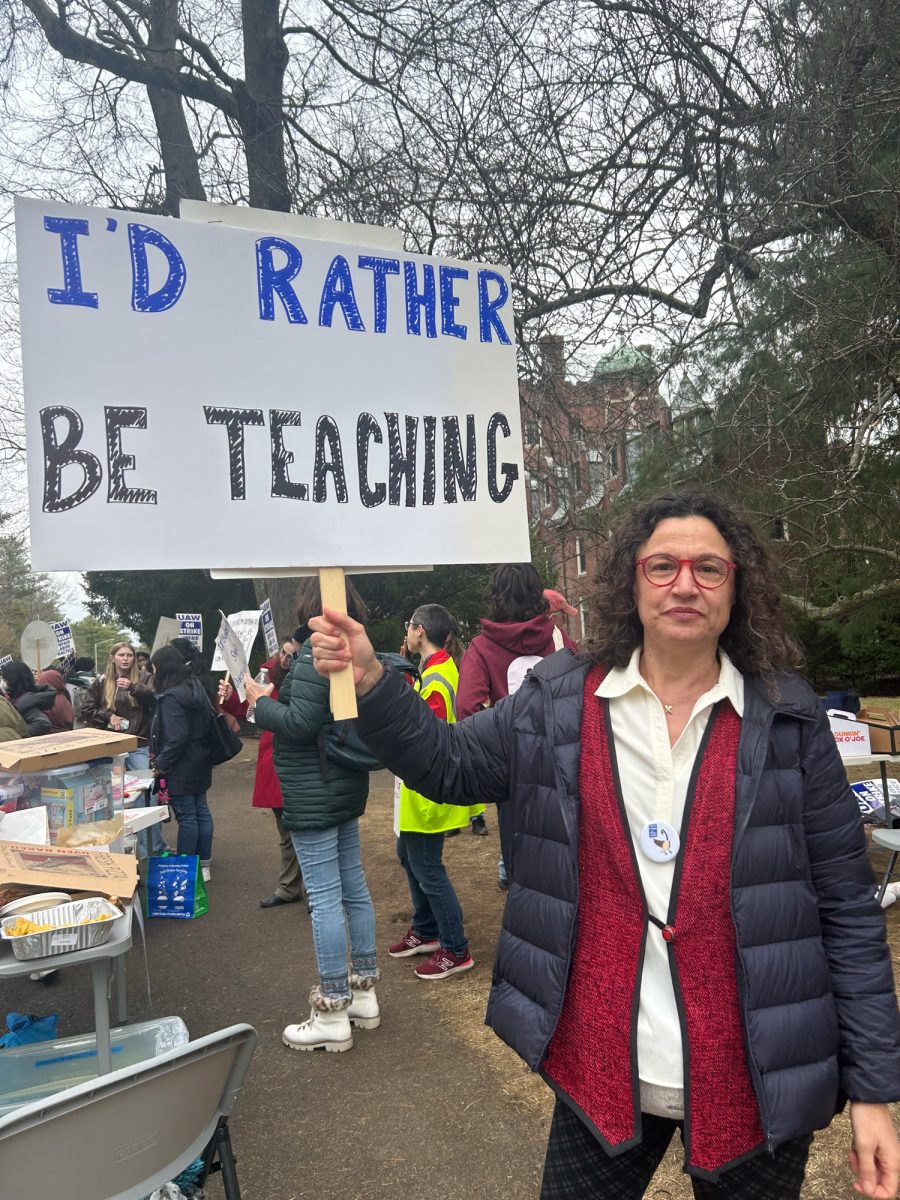

How can a victim of harassment, both online and in-person, be expected to find any help when their main options are a costly legal route and a reluctant police force?

These same kinds of inconsistencies and cracks exist in our campus judicial system. Much has been written about how ineffective Boston University’s sexual assault reporting systems are. Disparate offices distributed across campus — from ResLife to the Sexual Assault Response and Prevention Center, to the Title IX offices, to the Boston University Police Department —- make reporting sexual assault a long, paperwork-heavy process, with someone’s case being juggled from office to office.

The long, backlogged process of filing a sexual harassment or assault case may allow for survivors to end up in the same class as their abuser, or the same dorm building, with little legal recourse or support.

Moreover, even though SARP has been called a useful resource by many survivors, it does not offer many actionable legal steps for survivors to protect themselves.

What we need as students is a reporting office that can take actionable steps to protect survivors. This office must empathetically advocate for survivors — and have the power to prevent survivors from sharing space with their abuser and trust their safety will be protected.

In having a stable office that survivors can depend on actively working on their case to enact timely actionable repercussions and safety measures, students can finally feel their safety is a priority at this University.

We as young adults understand these horrible things may happen regardless. But this does not mean that we should be resigned to our legal and University system being wholly inadequate to guarantee our safety.

We should never wait until it’s too late to act on disturbing behavior that could lead to bodily harm or murder. If clear actions can be taken to prevent serious harm to an individual, why are we not taking these steps to ensure everyone in our community is safe?

Horrible things have happened and will continue to happen. Why not do something about it?