Julia Roberts and George Clooney’s new romantic comedy “Tickets to Paradise” is hardly noteworthy. Letting two randomized Sims loose in Sims 4: Island Living would result in a more interesting film, because their pre-programed mechanical movements could at least result in an accidental house fire.

There is no fire in “Tickets to Paradise,” no unbridled emotion and no life. It feels like a romantic comedy from five years ago. But my issue with it is not that it’s dated. It is that it feels entirely removed from reality.

The problem with this film speaks to an issue I’ve been having with movies for a while now — the film presents a story that lets itself be swallowed by its own structure and convention.

I know this film’s purpose was not necessarily to be a great piece of art. Its purpose as a commercial romantic comedy is to entertain. But let’s consider, for a moment, the reason we as human beings tell stories in the first place: we tell stories to be understood.

There are certain aspects of real life that are too strange or painful to be described exactly, and so we use fictional characters and settings to try to communicate a real feeling. Centuries of writing have produced certain formulas and structures through which we can more easily communicate these feelings. As notable playwright Vaclav Havel once said in a speech, “As soon as we begin to realize that one thing may follow another…that spacetime, and thus the world, are structured, we begin to experience a sense of the dramatic.”

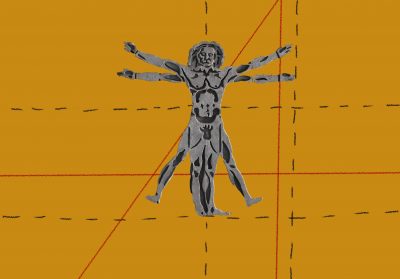

The most famous of these structures is the hero’s journey, which “Tickets to Paradise” closely follows. A divorced couple is forcibly reunited at their daughter’s wedding. In the hero’s journey, this is “the call to adventure.” They decide their daughter’s marriage to an Indonesian seaweed farmer is unacceptable, and team up to break them up. In the hero’s journey, this is when they cross into the “unknown” territory — learning how to work together despite their dislike for each other.

They conduct various antics of sabotage, throughout which they share lingering glances and dance drunkenly. There is the customary man getting kicked in the balls joke. They are vaguely racist towards their daughter’s fiance and Indonesian customs in the subtle way of Baby Boomers. In the hero’s journey, these events are the challenges that they face along the way.

Their daughter eventually uncovers the ruse, and she’s devastated and hurt. In the hero’s journey, this is the “abyss” — the lowest point — in which our heroes experience a moment of revelation.

Julia Roberts and George Clooney’s characters, transformed by the journey, realize their mistake and allow the wedding to proceed successfully. The film ends with the two parents reconciling their love for one another. This marks the end to their hero’s journey, with the two of them returning to a status quo.

Formulas like the hero’s journey are meant to provide a structure through which the story can communicate meaning. But there is no meaning to be found in “Tickets to Paradise” — there is only structure. The film is not grounded in any real emotion, but rather limits its focus to the same old tropes that came before it.

The hero’s journey is often depicted as a circular journey. When I first saw a diagram of it, and saw that poor little guy suspended in the circular cycle, I felt as if I were watching a hamster wheel. How can every story be so neatly contained into these ordered steps? At what point is limiting our narratives to a sequence of plot points depriving them of meaning?

In addition to being a playwright, the aforementioned Havel was also the president of Czechoslovakia. It makes sense that a statesman would love structure, but what about all of us ordinary people, who may feel restrained and bored by law and order? How are we meant to feel anything if the narrative is being so painstakingly contained in that damn circle?

At what point does the hero’s circular journey extend outwards, towards the audience? At what point is the hamster set free?

I can acknowledge that stories require some kind of structure to make coherent sense. I cannot offer any viable alternatives to the hero’s journey, though I’m sure there are many out there. But one thing I do know is that “Tickets to Paradise” took me through all the steps of a hero’s journey, and still I ended up feeling nothing.

I go to the movies to be moved. I’d rather be confused by a meandering film that seems to stumble onto its feeling, than understand a story suffocated by its structure. So please, for the love of god, let that poor man out of that circle.

Set the hamster free.