State legislators have pushed to raise taxes on alcohol in a legislative briefing on Feb. 9, backed by a December report that drinking caused almost 5% of all deaths in Massachusetts from 2015 to 2019.

The tax would help fund alcohol-related costs paid by the state. In 2010, the last year data was available, those costs added up to $2.26 billion.

Boston University School of Public Health professor David Jernigan and SPH research assistant Xixi Zhou co-authored the report to inform Massachusetts’ alcohol policy with concrete data. They found drinking kills an average of 2,760 people per year in the state.

“These are all completely unnecessary deaths,” Jernigan said. “There are really basic, concrete things we could do to reduce and prevent them.”

In order to discourage drinking and fund state spending on alcohol, Rep. Kay Khan proposed doubling the excise tax on alcohol in House Docket 3101, filed this January.

Sen. Jason Lewis, who filed a similar bill in the state senate, voiced his support for the measure.

“Public health experts recommend raising alcohol taxes because this is one of the most effective strategies for reducing and preventing underage drinking, especially heavy consumption,” Lewis wrote in an email.

Khan said the tax addresses a bigger issue of avoidance within the alcohol issue.

“There has to be much more attention to alcohol, which has been kind of this sacred cow nobody wants to talk about, and nobody wants to think about,” Khan said.

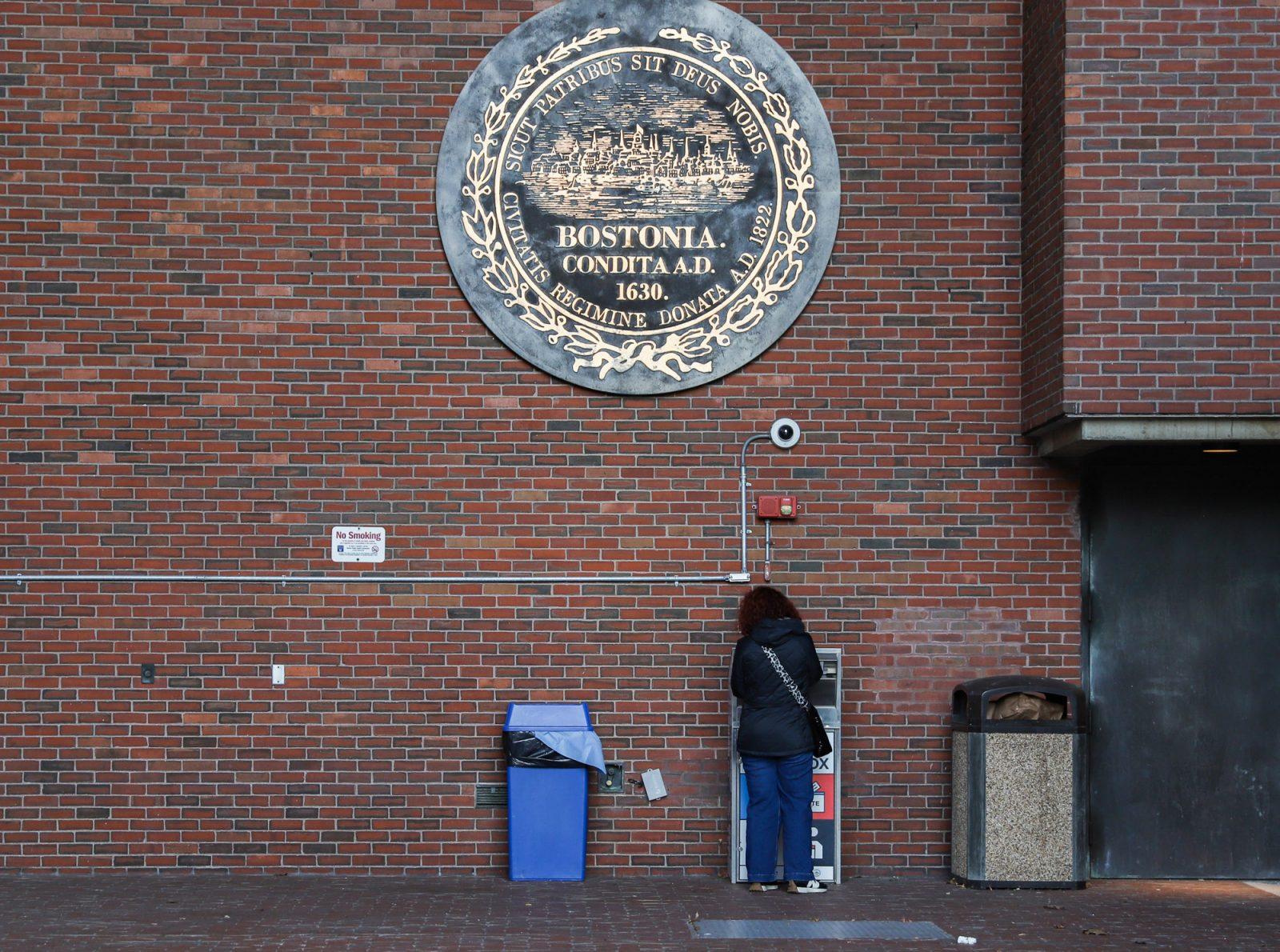

In 2009, Massachusetts implemented an increase in sales tax — from 5% to 6.25% — which added on the excise tax on alcohol. Khan said the alcohol industry responded by lobbying for a ballot question about the sales tax.

Voters rejected the new tax, and the following year it was abolished.

Currently, Massachusetts has around five times the amount of alcohol licenses that Pennsylvania and New Jersey permit. The number of alcohol licenses, permits and certifications in the state rose 63% from 2011 to 2019, and the excise tax on alcohol hasn’t increased since 1980, according to the report.

“It’s just a steady creep, creep, creep,” Jernigan said. “This isn’t a normal product, this is a highly-addictive product, but it’s also a highly-damaging product.”

Khan has tried to increase the alcohol excise tax for over ten years.

When Khan and other legislators filed a bill to double the tax in 2021, Massachusetts Package Stores Association, a nonprofit representing local retail alcohol stores, pushed back. The organization said raising excise taxes threatened local businesses by making it harder for them to compete with out-of-state retailers.

Khan hopes this session, Jernigan and Zhou’s report will be “really instrumental” in convincing Massachusetts to implement a tax increase.

Sen. Will Brownsberger, who is not one of the bill’s sponsors, was less sure.

“I’m very supportive of diminishing alcohol, but the tax mechanism is one that’s perceived as harsh, and it’s not likely to be the one that’s going to really take off,” Brownsberger said.

Annabelle Schultze, who lives in South Boston, said given how much tax she already pays on drinks at bars, she wasn’t in favor of a tax increase on alcohol. She also doubted whether a tax increase would reduce the number of alcohol-related deaths or if the tax revenue would make a noticeable impact on funding healthcare.

“I feel as a resident of Massachusetts that often I don’t see that money showing up in relief efforts,” she said.

Arelai Ephraim, another Massachusetts resident, also had misgivings about the tax but said a middle ground could be possible.

“If it was like a dollar and it was a negligible amount and people didn’t notice it but it helped the state, that would be a win-win,” Ephraim said. “But if suddenly your favorite wine goes from $15 to $25, I think that’s noticeable, and people will get angry.”

Excise taxes fall on alcohol distributors. Consumers feel the effects indirectly when companies raise the price of their product to cover the extra cost.

Jernigan said the benefits of the policy outweighed any costs incurred by consumers.

“The amount more that each person will make is so dwarfed by the level of resources that we could raise that could be spent on dealing with the problems,” Jernigan said.

He added that there is new research on the consequences of drinking — such as a causal link between alcohol and female breast cancer and alcohol’s “bi-directional relationship with mental health.”

“What I like to emphasize about alcohol taxes is four words,” Jernigan said. “Alcohol taxes save lives.”

BU alum • Feb 22, 2023 at 2:12 pm

I support an increase in alcohol tax. A proved important and effective measure for public health. As Jerrigan said, “This isn’t a normal product, this is a highly-addictive product, but it’s also a highly-damaging product.”

Tom Alciere • Feb 21, 2023 at 9:09 am

People have a right to drink themselves to death. It’s their body and their life and as the song goes, “Ain’t nobody’s business but your own.”

Limiting the number of licenses means certain people who get picked to have a license can make money. In a free country, anybody could buy any house on the market and open a saloon. The owner would decide who may enter, who may get served, what prices to charge and what hours to operate. There would be no minimum drinking age because parents would not suffer or permit their child, who lives in their house, to enter. Drunks could walk home instead of driving.