October 7.

It was the end of David Kotton’s days bringing Boston University Students for Israel members together over Israeli food. Now, these meals are replaced by serious speakers, vigils and creating space for students to grieve.

“It’s going to be heavy. But these are heavy times and that’s what it demands,” said Kotton, a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences.

It was the start of an anonymous junior going to bed anxious about what she would wake up to in the morning. She didn’t know if there would be another attack that would compel her to put together a demonstration for BU Students for Justice in Palestine, for which she is the co-president.

In a city known for being a college town, a city where presidents of Harvard University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology drew controversy for their comments in a congressional hearing on antisemitism last week and a city where people of all backgrounds come together to live and study, universities have had to try to balance a space for free speech with a safe one.

There are few events in recent history that need not be named by anything but its date. October 7 is one of them.

Since then, Kotton said, “Most people that care in some way about the conflict in some way can feel it.”

That “it” is tension — a word student activists across the board used to describe the climate on BU campus.

At the University of Massachusetts Boston, though, things were “peaceful,” according to Undergraduate Student Government President Kaushar Barejiya. She said she hadn’t heard about an instance where public safety had been compromised on campus by students when she initially spoke to The Daily Free Press in mid-November.

This week, however, UMass launched an investigation into antisemitic graffiti found in bathrooms in several buildings on campus. University leaders said in a letter to the UMass community that they were made aware of the graffiti on Monday Dec. 4, and the investigation is ongoing.

Barejiya said she is looking forward to hearing from student affinity groups about how they are feeling in wake of the graffiti. For now, she is “trying to process” the events personally.

As of Saturday, she said there have not been more demonstrations or walkouts on campus.

Prior to that, first-year Northeastern University law student and SJP organizer Mariam Hassan, who completed her undergraduate degree at UMass, said she believed her alma mater handled tensions on campus a lot better than Northeastern.

Initially, Hassan said UMass’ faculty members leading teach-ins, collaborating with students and participating in events on campus contributed to an overall climate more conducive to discourse.

“It makes me really feel very disappointed in Northeastern, especially being a school that claims to be so liberal and so pro-discourse in academic discussions,” Hassan said.

However, the manner with which UMass handled the graffiti has changed Hassan’s perception of her alma mater. She said she doesn’t see universities doing much to directly address the antisemitism and anti-Arab rhetoric behind incidents like this, instead she said they focus on “whether or not they think a slogan is offensive.”

With Harvard’s president’s comments last week and the president of the University of Pennsylvania resigning, Hassan said UMass’ investigation adds “to an overall climate that’s not isolated to just one campus.”

In early November, UMass’ interim Chief of Police Kenneth Sprague helped a leader from the university’s Muslim Student Association set a route for a walkout that would keep it on campus, and thus under the jurisdiction of UMBPD rather than the state police.

“It went smooth as silk,” Sprague said. “That night I was home, sitting on the sofa with my wife and [the student] sent me a text. And I tell you, it was unbelievable. I almost got choked up over it … I know what’s going on all these other campuses, a lot of them have their hands full, and I get this Muslim student thanking me for everything that we did that day.”

Sprague said the MSA student called him on his personal cell phone number — which he offers to organizers — during the walkout because she couldn’t see the officers.

“We’re here,” he told her. “We’re watching everything, we’re making sure you are all set.”

Sprague said he aims to support students, and be visible where necessary, but “stay out of sight” at demonstrations like this.

Chief of Boston University Police Department Rob Lowe said he found that a visible presence of officers in uniform throughout campus is useful for cultivating a sense of safety.

“I have heard from students that have expressed that they are not feeling safe on campus,” Lowe said. “In response to that, I tried to determine exactly what that means for people, and a lot of times, I feel like there hasn’t been specific incidents that they’re referring to, but just a general sense of not feeling safe.”

Lowe encouraged students to reach out to BUPD if they feel the department should be present somewhere on campus that they aren’t already.

“If there’s any way that we can be involved in conversations with students to make people feel safer, we’re willing to do that as well,” he said.

Kotton said BUPD have been present at “pretty much all BUSI events,” which he said makes him feel physically safe.

BUPD has also been present at all SJP events, according to the junior, but this has raised concerns among the organization’s members about police brutality on college campuses.

Faisal Ahmed, a senior in CAS, said the Muslim community is “skeptical” of police in general after 9/11, which he believes makes community members hesitate when submitting reports of harassment or Islamophobia they experience to the BUPD.

“To me, there are virtually no ways that BU supports Muslim or Arab students on campus in an institutional capacity, so as a consequence, there are virtually no ways in which BU can protect those students,” Ahmed said.

Shayna Dash, a sophomore in the Wheelock College of Human Development and a recruitment chair for BUSI, regularly speaks to BU administration regarding antisemitism on campus. Currently, she and a colleague are pushing the University to officially adopt a definition of antisemitism into their code of conduct.

She supports the definition of antisemitism published by BU’s Department of Community and Inclusion, which comes from the U.S. Department of State. However, because the definition is not currently codified, Dash believes doing so will give students a better understanding of what, exactly, antisemitism is.

“The fact that the administration tries to live in the gray more by not having [any definition] is really difficult,” Dash said.

Mark Antar, president of Huskies for Israel at Northeastern, said urging administrative action has been “a struggle.”

While the University assures him he’s heard, Antar said there’s a “100% correlation” between the lack of “decisive action” by Northeastern and how safe he feels on campus.

These days, Dash hides her Jewish star ring by turning it toward her palm — an action she is now cognizant of every time she puts it on.

“It feels like everyone kind of hates you in a way,” Dash said. “Like everyone really just despises you for something that you can’t control.”

When walking down Commonwealth Avenue as an Asian woman wearing a keffiyeh, the junior said she feels unsafe.

“It has definitely exposed me to a certain level of uncertainty, but obviously I still choose to do that because I think it’s important,” she said.

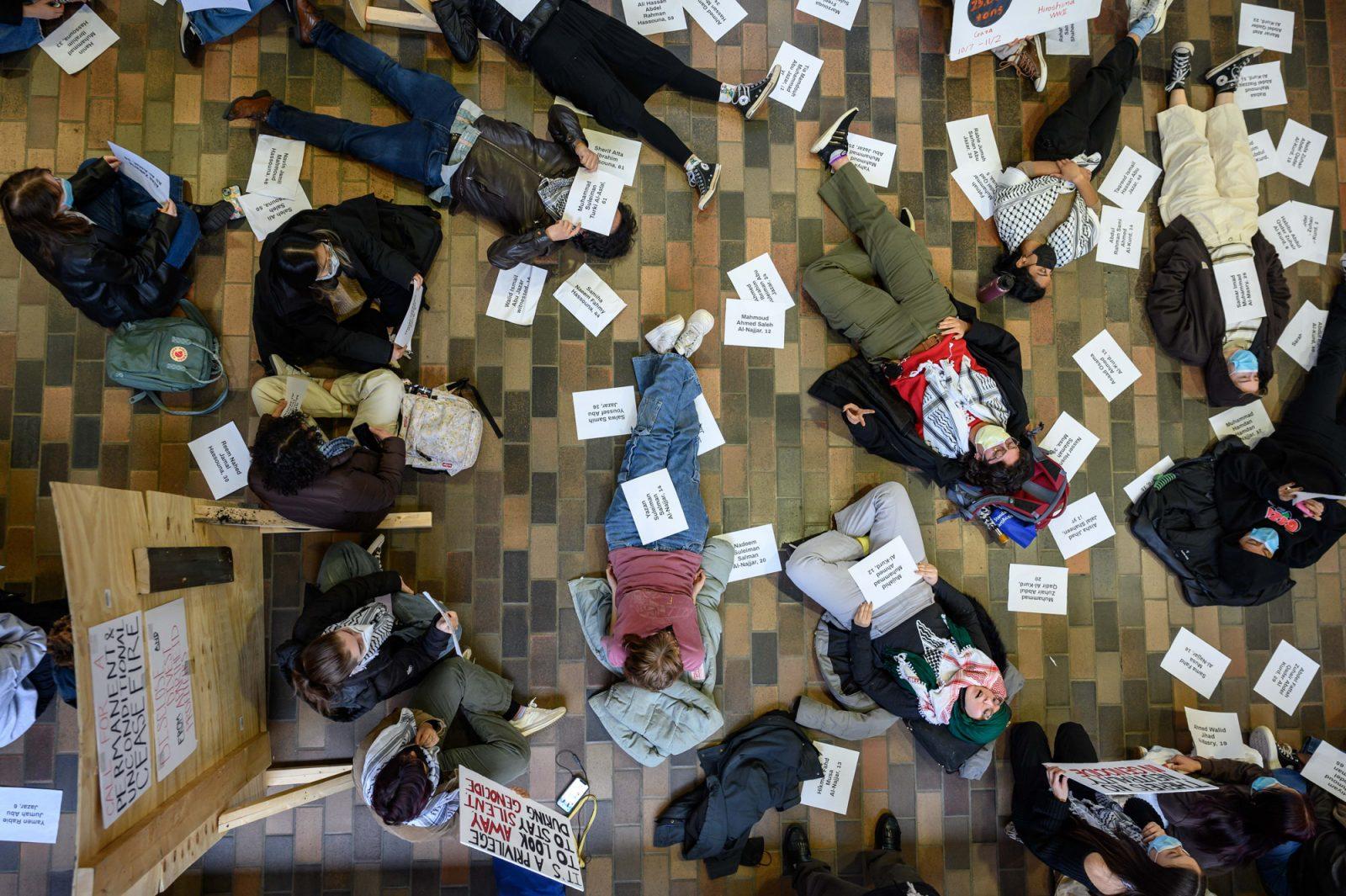

At demonstrations — including one last Friday in the George Sherman Union — students have taken pictures of SJP organizers without their consent, and she said people accused her of supporting rape and shouted “discriminatory words” at her. She believes students feel comfortable doing this because she says the University has not come out to say “discrimination will have consequences.”

On Oct. 10, BU released a statement regarding the conflict. Since then, the University has not issued a follow up.

“We all feel the tension,” Kotton said. “It weighs on us quite a bit. We all talk about how we’re constantly reading the news and always upset by the news and yet we can’t really look away from it.”