The White House formally declared Tren de Aragua, a Venezuelan criminal group, a Foreign Terrorist Organization March 15.

In the proclamation, President Donald Trump declared Venezuelan citizens aged 14 and older who are members of the TdA and are not naturalized or lawful permanent residents to be Alien Enemies under the Alien Enemies Act. He called for executive agencies to collaborate with law enforcement to detain and remove TdA members from the country.

“I find and declare that TdA is perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion or predatory incursion against the territory of the United States,” Trump wrote in the order.

The Aliens Enemies Act was passed as part of the four Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798. At the time, the U.S. stood on the brink of war with France, and the act allowed the president to detain, relocate or deport non-citizens from a country considered an enemy of the U.S. during wartime.

The Alien Enemies Act has been invoked only three times in U.S. history, each during significant military conflicts.

As war was never officially declared against France, the Alien Enemies Act was used throughout the War of 1812, World War I and World War II. While President James Madison did enforce some restrictions on British nationals during the War of 1812, the Alien Enemies Act had the most significant ramifications in the two world wars.

During World War I, President Woodrow Wilson imposed measures such as surveillance and mandatory registration with the police onto German nationals. More than 6,000 Germans were placed in internment camps and more than 480,000 Germans were registered by the U.S. Marshals Service as alien enemies.

The most notorious application of the Alien Enemies Act occurred under President Franklin D. Roosevelt during World War II, following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Roosevelt signed Proclamation 2525 under the Alien Enemies Act, granting the government the authority to arrest, control and remove suspected Japanese Americans deemed dangerous to the safety of the United States Dec. 7, 1941. German and Italian Americans were targeted as well.

A few months later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which expanded the scope of Proclamation 2525 by authorizing the relocation of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast.

Consequently, around 110,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry — two-thirds of whom were American citizens — found themselves forced into concentration camps within the United States. Thousands lost their homes and businesses for “failing to pay taxes” during their internment and continued to face persistent discrimination from civilians upon their release.

Japanese Americans were labeled as alien enemies — including both the Issei and Nisei. The Issei referred to first-generation Japanese immigrants who were ineligible for American citizenship because of earlier exclusionary legislation. The Nisei referred to second-generation Japanese Americans who held birthright citizenship.

The U.S. government also offered to intern alien enemies living in Latin American countries at the time and even recommended specific nationalities for deportation.

As a result, more than 6,600 individuals of Japanese, German and Italian descent, along with their families, were deported from more than 15 Latin American countries to the U.S. for internment. Most, if not all, of those deported never received any form of due process.

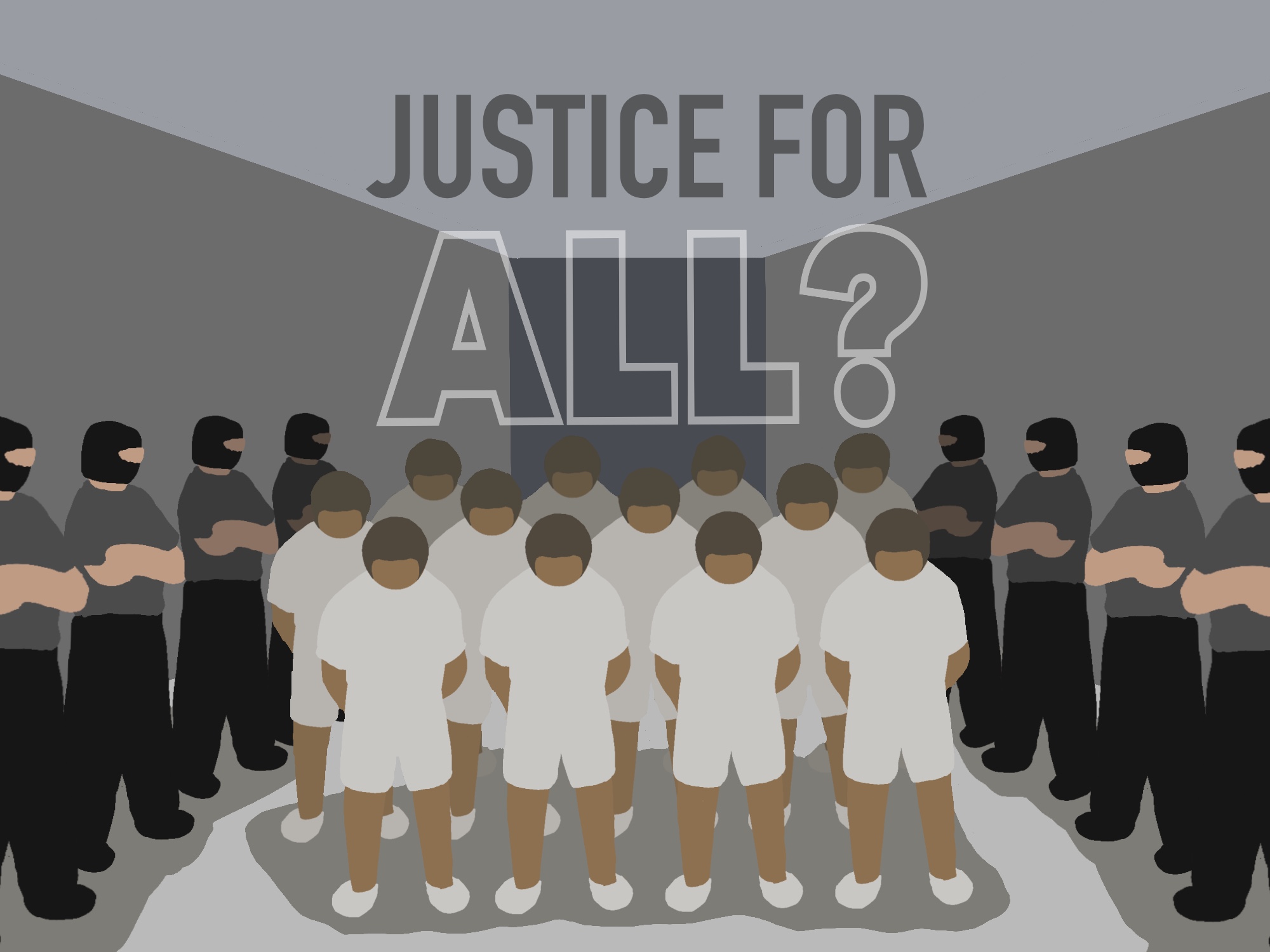

The Alien Enemies Act specifies that the president can only use its authority once Congress has declared war. However, the Trump administration has allegedly already deported more than 200 Venezuelans suspected of being TdA members to El Salvador, despite a federal judge ruling to stop two deportation flights.

As of now, Chief U.S. District Judge James Boasberg has ruled any Venezuelans facing deportation under the act must be given a chance to deny their membership in the gang before deportation occurs.

Furthermore, Trump signed an executive order in January to revoke birthright citizenship, a move that echoes the painful injustices faced by Japanese Americans throughout World War II.

For many Asian Americans, and immigrants in general, birthright citizenship has been a crucial pathway for establishing roots in America.

As new policies under the Trump administration unfold, it becomes transparent how disproportionate the impact on immigrants and minority communities is. When fundamental civil rights are violated in such a way, can America still claim to be the land of “justice for all?”