Inclusion. Freedom. Equality. Options. These one-word responses exemplify what true accessibility means for a crowd of able- and non-able-bodied professionals who gathered Tuesday to discuss how their workspaces fall short in meeting their needs.

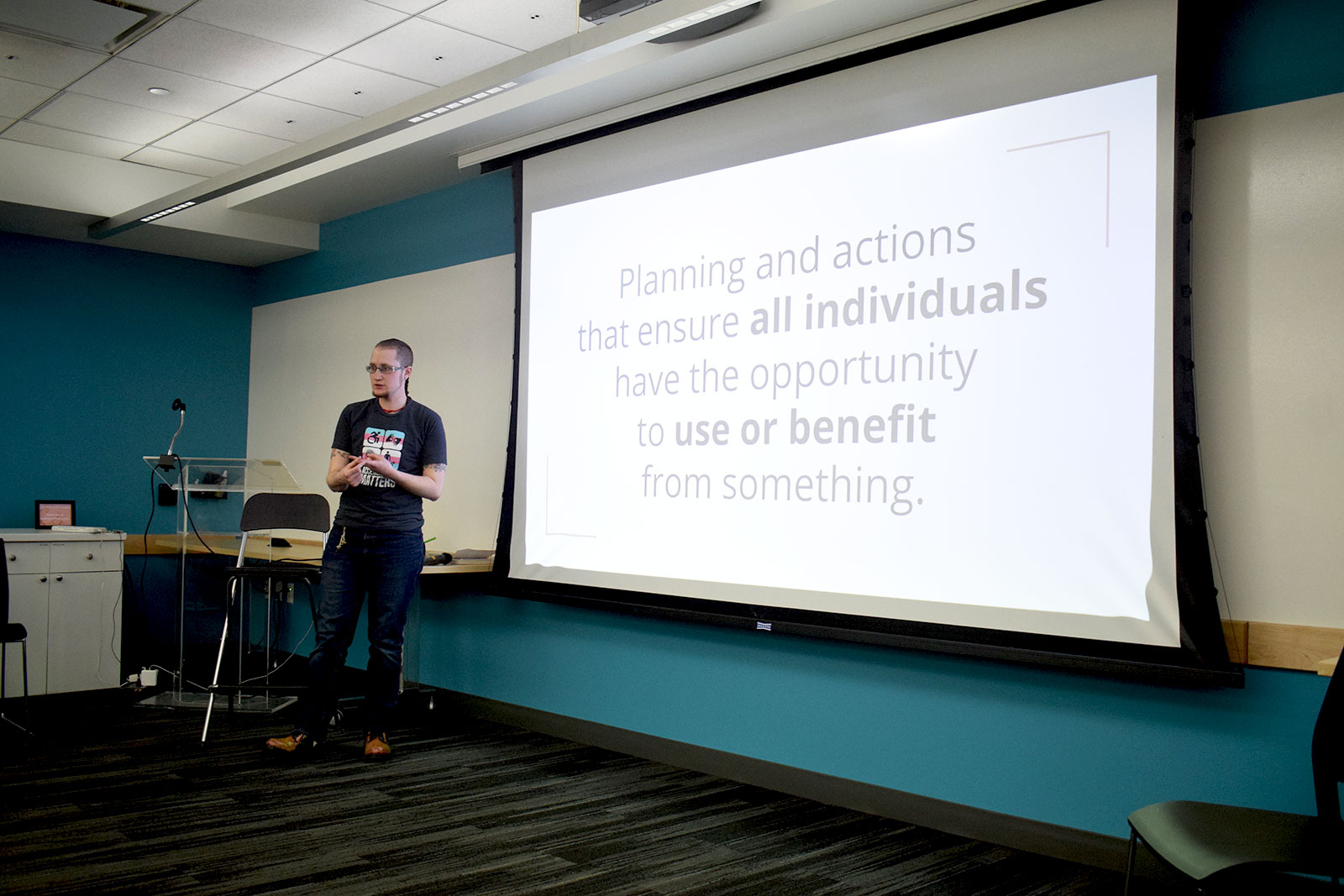

Rhys McGovern, a speech and language pathologist in the Boston area, hosted a workshop entitled “Accessibility Matters: Accessibility in the Workplace” at the Cambridge Innovation Center.

Though he walked unassisted at the event, McGovern uses a wheelchair as needed when his disability prevented him from being ambulatory. He said having a wheelchair was not a bad thing because it gave him a chance to be mobile again. That feeling of freedom, however, did not last long as accessibility and discriminatory barriers began blocking his autonomy.

“Getting a wheelchair was the most freeing thing that I have ever experienced in my life, I was able to check out all types of wheelchairs and find which works for me” McGovern said. “I was thrilled. But then, I realized that I couldn’t go places and do things.”

Cambridge resident Ragan McNeely, a self-employed psychotherapist and father of a son who is a wheelchair user, said he used creative solutions in his own life to help his patients, such as eliminating the idea of a waitlist in order to provide a more accessible and immediate service.

McNeely, who attended the event, said the workshop offered insight to how creativity and critical thinking can help increase accessibility.

“Universal access to something [is] a creative process,” McNeely said in an interview. “I like that about it.”

McGovern said he hoped the workshop would encourage a stronger understanding of accessibility and the barriers that limit people’s independence, particularly in the workplace.

“The last thing that you want in a workplace is for other people to have to do stuff for you,” McGovern said at the event. “You want to be an independent adult doing independent work.”

But McGovern said this access and independence is often hard to achieve.

“A lot of people think accessibility is [just] physical,” McGovern wrote in an email. “They think about stairs and elevators and doors. But that is only one small part of access.”

McGovern said 25 percent of people across the nation have at least one disability. Without creating universally accessible products and spaces, individuals and companies miss out on appealing to a quarter of their potential consumers, according to McGovern.

“It’s a reality of being [a] human in bodies that are squishy that at some point, you will experience a disability. And if we design for that reality, suddenly everything changes,” McGovern said. “If a design works well for people with disabilities, it works better for everyone.”

Though installing new structures can be pricey, McGovern said not all solutions require a huge investment. He said creative fixes, such as removing carpets or rugs in a workspace, is an easy solution to make spaces more accessible for people using manual wheelchairs.

In the presentation, McGovern included a “bingo board” of phrases that people with disabilities regularly hear, including, “I wish I could sit down all the time,” and “you don’t look/act disabled.” These prompted the audience to share intimate stories of personal discrimination, and what they did about it.

David Wieselmann, who became a wheelchair user after an accident, created an app and website called “Where to Wheel” as a tool for people with disabilities to find places that are truly accessible and reviewed by people who also share a disability. The entrepreneur said the idea stemmed as a result of the challenges of inaccessible places.

“The more I went out I realized, ‘Okay, if I was in [an] electric wheelchair, maybe I could use this place,’” Wieselmann said in an interview. “That’s when I had the epiphany of “Where to Wheel.’”

Beyond addressing these issues on a corporate scale, McGovern discussed ways the audience can take individual action to change the work environment. He said one of the ways is to acknowlege and confront discrimination against someone who is or is perceived to be disabled.

Further, McGovern said examining language is essential to making a change in workplace culture and is one of the simplest, yet most difficult things to do.

“Learning to recognize and address access barriers and ableism,” McGovern wrote, “is the most powerful step individuals can take toward creating and supporting a more equitable workplace and society at large.”