This past year, education has forced schools into an online revolution, with educators adapting to remote instruction. Educators argue, however, given the divisive politics of today, there is far more to adapt to.

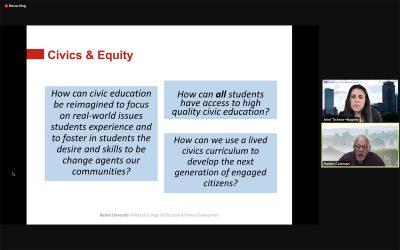

Leaders from the Boston University Wheelock College of Education and Human Development and around the country participated in a webinar Thursday titled “Reimagining Civic Education for Equity” to discuss civic education both in Massachusetts and nationwide.

The panel hosted speakers from policy, education, human development and leadership backgrounds.

At the panel, Ariel Tichnor-Wagner, the program director of educational policy studies, and Dean Emeritus Hardin Coleman of Wheelock presented their research findings on civic education in the context of education reform.

In an interview, Coleman said historically, discussing civic education has been neglected in urban school curriculums.

“Over the past 40 years of education reform, there’s been this huge focus on literacy and numeracy and now science,” Coleman said, “and a lot of very important things have been pushed to the side in the curriculum: social studies, civics education, arts and other topics, particularly in urban settings.”

From a policy perspective, Reuben Henriques, a history and social science content lead of the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education and event panelist, said in an interview it is important to discuss civic education across different fields of study.

“I think one of the themes that came up in that panel that is so powerful is just the importance of cross-sector collaboration around civic education,” Henriques said, “equity and civics more specifically.”

He said in an interview his work for the state department involves both guiding instruction and holding schools accountable. He said there has been a recent effort to emphasize civic education.

“That was like definitely a deliberate choice,” he said. “Why do we actually want students to learn history and civics? It’s so that we can prepare them to begin to take on an active role in democracy and prepare them for civic life.”

Henriques said insufficient civic education reflects the divisive environment today.

“We see every day the problems caused by a lack of civic education,” he said, “whether in just online debates that sort of devolve into name calling or the insurgency in January or this frayed civic fabric.”

He said he sees a reform of civic education — though a “monumental” task — is a way to give students the skills to make societal change.

Many college students, including those studying at BU, are actively engaged in civic education through participation in various social justice, climate awareness and community engagement clubs.

Coleman said while protesting is important, it’s not the only way students can make societal impacts.

“What I would hope that students would take from this is understanding that regardless of their major, from engineering to art history to dance, whatever your major is, there are ways you can become involved as a citizen,” he said.

For example, he said engaging in educational activities, such as tutoring and assisting local health communities, are ways to be a civic citizen.

Verneé Green, the executive director of Mikva Challenge Illinois, said at the event the national organization empowers young people to be active, engaged and educated citizens by giving them voice in their communities.

“We do some direct youth work,” Green said. “[Such as] nonprofit organizations or after school organizations, we provide that support where young people actually get the chance to participate to actually engage and be civically engaged.”

Green said the organization also operates several youth councils, including one that works with the superintendent of schools to amplify youth voices. More programs offer young people the chance to direct policy advice on local issues — based on their personal experiences — to public officials.

“Allowing young people the chance to really live out their civic engagement,” she said at the event.

At the event, Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg, the director of CIRCLE at Tufts University — which studies how youth are engaged in democracy through education and promotes improved, further education — said equity is a key aspect of her work.

“Equity has to be the condition for all of the work we do,” she said.

Henriquez said though the panelists came from different backgrounds, they were aligned in an effort to address the gap in civil education.

“There was some really good conversation around what we see as our common challenge,” he said, “and what role sort of each of us has to play in helping to bridge that gap between where we are and where we want to be.”

He added the panel also shows the importance of collaboration between different sectors in civic engagement and how essential it is to keep making progress.

“I really do think that education is a way to build the skills and the dispositions that students need,” Henriquez said, “in order to be prepared to take action and shape our democracy.”