Usually random noise is a nuisance. We change the channel to escape the snow on our television sets and fiddle with the antennae on our radios to get the clearest sound.

But Boston University scientists have found a way to use random noise to help the elderly keep their balance by increasing the amount of sensory information they get from their feet.

Staying upright is a task that requires constant work. ‘It is like balancing a pencil on your finger,’ said Attila Priplata, a BU graduate student and the lead author of a paper about balance that will appear in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The human body has to make constant adjustments to maintain balance, and it is dependent on the information gathered from three systems: the visual system, the vestibular system, located in the ears, and the pressure sensors in the feet, Priplata said.

Many people lose sensation in their feet because of conditions like diabetes, stroke or advanced age. According to Priplata, this lack of sensitivity can lead to increased swaying and falls.

To combat this, a research team led by James J. Collins, a professor in the Biomedical Engineering Department, designed a platform with hundreds of small perforations. When test subjects stood on the platform, small nylon rods poked through the holes and gently prodded their feet.

Even though the individuals could not sense the rods beneath their feet, their bodies adjusted to the random signals. With the right levels of prodding, 75 year olds reduced their swaying to the same amount as BU students in their 20s who weren’t using the platform.

The weaker pressure signals in the feet combine with the introduced random noise from the platform to yield a signal that is above the threshold at which the nerves detect pressure, causing the nervous system to fire. Information is rapidly transferred to the brain and returns to the feet, which make the necessary adjustments.

According to Collins, the signal problem is a phenomenon called stochastic resonance, and levels of random noise can increase the detection of a weak signal. Stochastic resonance has been studied for at least 20 years, but this is the first time it has been used to improve balance, Collins said.

Priplata has taken the platform experiment a step further. He has been creating a prototype of insoles that will be able to duplicate the same benefits of the platform. Three small, circular discs within the insole send vibrations to the feet. Preliminary tests have already shown that the prototype works as well as the platform in reducing sway, Priplata said.

One of Priplata’s first projects is to reduce the thickness of his prototype insoles the one-inch thick prototype cannot yet be slipped into shoes. He said he is looking at gel-based materials that will use the energy created by walking to produce the random vibrations rather than relying on battery powered discs.

‘A third of the people over the age of 65 fall each year,’ Collins said. This poses a huge concern for health care professionals. Injuries that result from falling can mean the difference between being independent or living in a nursing home, he said.

‘Right now the only thing we have to offer is a cane or walker,’ said Jason Viereck, a physician at the BU School of Medicine. ‘Physical therapy can only go so far and so it is really great if there is something that can augment one of the systems we have for balance.’

Lars Oddsson, a professor at the Neuromuscular Research Center at BU, approaches the issue of falling in a slightly different way. Oddsson’s interest is in exercising and coaching individuals to respond faster to a change underfoot. ‘We actually push people around, and we use unstable surfaces that they walk on,’ he said.

Unlike Collins’ stable platform, Oddsson’s is designed to simulate slipping on a patch of ice. Preliminary results have shown that healthy individuals tripled their reaction time after training. ‘So if you are looking around, and if you trip, you are not going to have a long reaction time and fall flat on your face,’ he says.

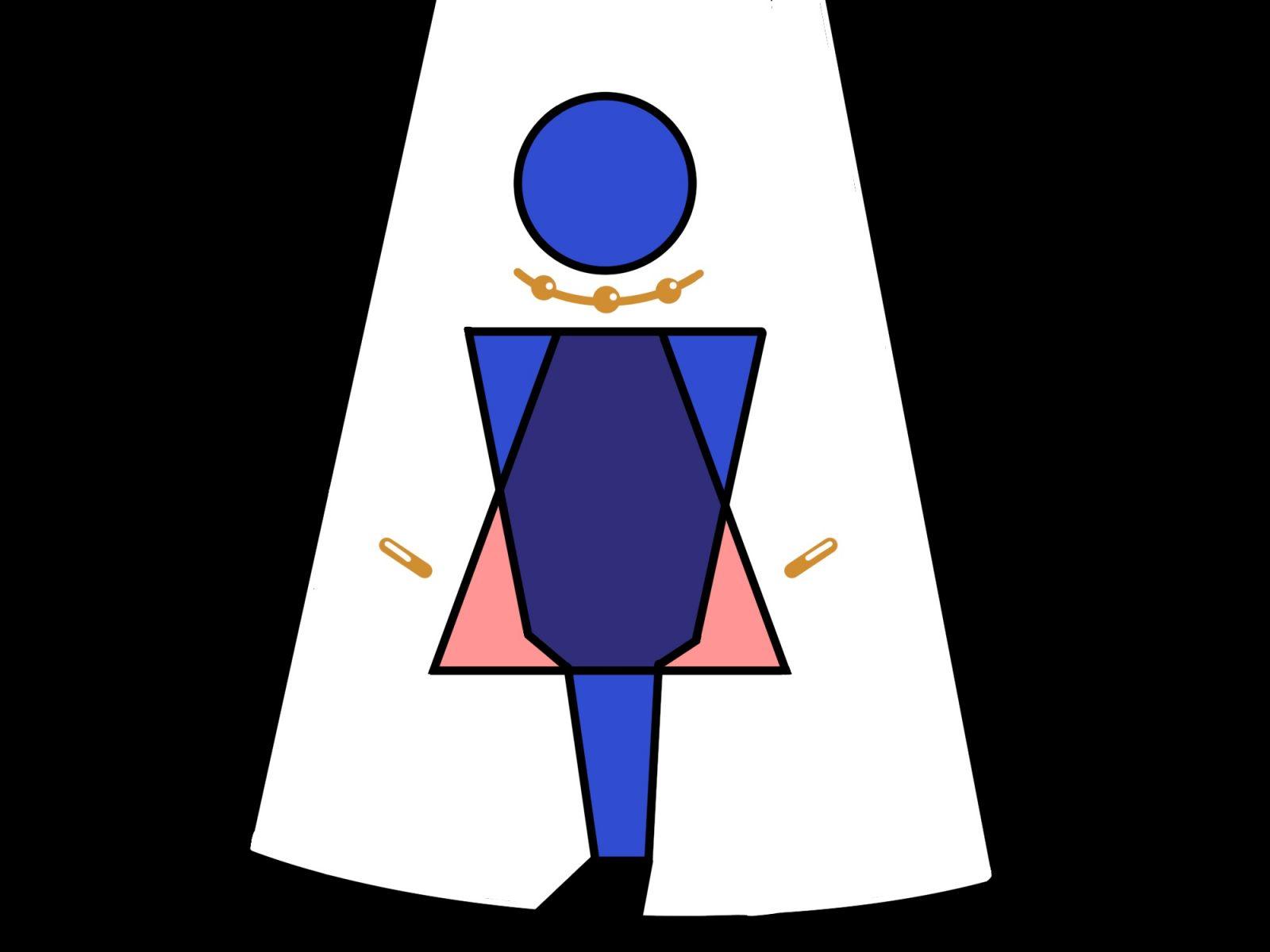

Oddsson and his colleagues are also working on a balance-improving device for the elderly. They have developed a prototype of a vest that measures how much an individual tilts his or her body. If you lean too far forward, the vest starts vibrating in the front to tell you to lean back. According to Oddsson, this technology has already been used in the navy and air force.

‘Special operations pilots have been blindfolded, and they can fly using this vest,’ he said.

‘This is different from Collins, who is trying to enhance a function that is already there. We are trying to substitute it somewhere else on the body,’ Oddsson added.

‘It is a different approach, though they partly complement each other.’