NOTE: The persons involved in this story chose to remain partially anonymous.

David’s future could have been an easy case.

The 21-year-old from Amherst was never confused about his future. He never decided to veer off his chosen track: to work on cars. He did not gravitate toward an inaccessible or risky career. He had no interest in being an artist, a doctor or an actor. He wanted to work on cars, and his Autism Spectrum Disorder did not have to get in the way of that dream.

David, who chose to partially remain anonymous, is one of many young adults who went through the Massachusetts statewide special education program, which provides specialized curriculum, counselors and activities to students with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

Beginning in preschool, students meet counselors and advisors that help them learn skills they can use to live independently. Once these young adults approach their graduation date, they begin to discuss placement options with their parents and school counselors in Individualized Transition Planning meetings. These meetings are designed to help students find their places in the world once they leave the public school system, whether that places is in a sheltered workshop, a college environment, a Massachusetts Rehabilitation Commission Independent Living Program (MRC), or at home with Department of Developmental Services checks.

Nonetheless, the funding for and the organization of this program leave many young adults like David with few-to-no options. However, there are currently two bills in state legislature may change that.

David is one of the many Massachusetts adults with a developmental disability. As a high-functioning person with ASD, David cleans up after himself, goes to school and work, procrastinates on the internet and plays video games — he was very excited to set up his new Xbox One — like any other 22-year-old. Yet he struggles with social communication, reading nonverbal cues and finding the words to express the world inside of his head. Get him going on cars, however, and he will talk for hours.

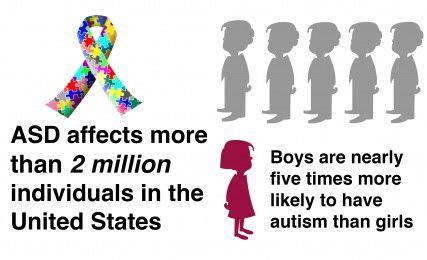

ASD diagnoses have increased 600 percent in the last 20 years, and yet Massachusetts is the last state in the country to only offer Department of Developmental Services support — monthly checks, residence placement assistance, job placement assistance, counseling, etc. to those with an IQ below 70.

That excludes a large number of people with developmental disabilities, including those who fall on the high-functioning end of the Autism spectrum, like David.

“It’s kind of like being lower-middle class,” said David’s father, Eddy. “You’re not poor enough for food stamps, but not rich enough to eat.”

Early on in his schooling, David’s parents reached out to the school in an attempt to discuss the possibilities for David’s adulthood. However, the school did not begin David’s ITP meetings until six months before graduation. The Massachusetts government recommends meetings begin two years prior to graduation.

Ineligible for DDS and rapidly approaching independence, David was offered only three major routes: MRC, which provides similar programs as DDS with less allocated funding (MRC is responsible for all varieties of disability, while DDS simply focuses on those with intellectual disability), a sheltered workshop (which will all be closed by 2015) or college.

He attended Westfield State University and dropped out within two years.

“I decided that it wasn’t really the right time for me, yet,” David said. “It was too fast … I made this whole new group of friends and sort of lost focus on what I was doing.”

At first, David went to a center for students with disabilities at Westfield to meet with an advisor, but after a sudden change in its administration, David slowly stopped visiting the center. Now able to choose his own level of involvement, David chose to stop attending meetings altogether — and, subsequently, to leave Westfield.

“We provide a rich array of programs for the developmentally disabled if you are 21 or younger — we have some of the best special [education] laws in the country,” said Senator Michael Barrett, chairman of the Committee for Children, Families and Disabilities in the Massachusetts state legislature. “Once you turn 22, you do fall off a cliff.”

David felt himself falling as well. His advisors recommended MRC for job placement, and David spent months trying to get ahold of a counselor who never responded to his emails or calls. When he was finally reassigned to a dedicated job placement counselor, she did not end up getting David a job, forcing him to turn to his parents for help.

His parents drove him from building to building with resumes for him to get his current job working in a pet store when he was already working on cars in high school.

David’s father, Eddy, is a well-known man in Amherst, and someone who was fortunate enough to know people willing to hire David. But David is not a typical case. Unlike other young adults with ASD, he was lucky enough to have parents dedicated to helping him succeed, who could afford to spend the time helping him find a job, and who understood they system enough to help him. Many youths with disabilities do not have resources available like David’s. Many of those youth end up depending on their parents for many years after graduation or living on the street.

“Too oftentimes, when people aren’t offered these services early on, they are likely to stay home and languish,” said Barbara A. L’Italien, director of government affairs for ARC of Massachusetts, an organization that provides services for people with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

Two bills in state legislature may improve conditions for youth with developmental disabilities: The Bridges to Success bill regulates the Individualized Transition Meetings, forcing representatives from whichever adult services agency the student and counselors choose to attend the ITP meetings. This requirement ensures the chosen option for the student is a good fit. It also forces schools to begin ITP meetings at least two years before graduation, so more students avoid the pre-graduation rush that David tried to avoid. Finally, it institutes more community programs for adults with disabilities, so various new graduates can meet and talk to others about how to become self-sufficient.

The second bill, Passage to Independence, provides an extra $23.4 million to the Department of Developmental Services to provide more options for people with developmental disabilities who are transitioning out of the school system.

Both of these bills heard testimony on Nov. 5 and are still awaiting judgment in committee. Many young adults with disabilities from across Massachusetts came to testify on behalf of both bills. Cassandra Agger, a 22-year-old from Waltham, said she believes the bill could protect her from a possibly desperate condition.

“I have a friend who has been homeless for six months now,” Agger said in her testimony. “I don’t want that to happen to me.”

Both bills suggest changes for the 2015 fiscal year, and no action has been officially made by the committee on children, families and persons with disabilities since the hearing. The bill was originally brought before state legislature one year ago.

Although no committee members have publicly opposed the bill, Senator Barrett said he would like to see a bill that encourages more assistance from independent entrepreneurs to help students with disabilities transition. For instance, he thinks the development of an online rating system, like Yelp, for state transition services would help students with disabilities and their families pick an agency.

“There are ways the state could help, but I’m interested in encouraging the private sector solutions to address the same question of the young person’s empowerment,” Barrett said.

David was not sure whether more meetings, more online resources or more funding would help kids like him find independence. More than anything, David just wants to go to automotive school, and his parents just want him to be happy.

“I want a job that I want to wake up for every day,” David said. “My biggest fear is that I’ll look for that job, hope for that job, find that job … work to get that job and then not get that one.”

Editor’s Note: The original version of this story said David is 22 years of age, but he is actually 21 years old. The story has been corrected.