With more than a quarter of Boston’s families with children living in poverty, a recent report by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute found that child poverty rates in Massachusetts have increased 6 percent between 2002 and 2012.

The 2014 County Health Rankings and Roadmaps report, released March 26, identifies key issues for communities by providing statistics and data, as well explaining solutions to improve conditions. Anne Roubal, assistant researcher for the report, said the project is designed so counties can see what changes need to be made.

“There’s always room for improvement,” she said. “Nationally, 23 percent of children under 18 are living in poverty, but there are counties that have over 60 percent of people, and nationally, it is growing.”

The data, which was provided by the U.S. Census Bureau and gathered during their 2012 Small Area Income and Poverty Estimates, shows 10 percent of counties nationwide have child poverty rates more than 30 percent. Nationally, 17 percent of children were living in poverty in 2002. That number rose to 23 percent by 2012, Roubal said.

“It is one of those measures that we can capture really well by measuring the federal poverty line,” she said. “There is a stigma about living in poverty, so you may not notice it, but there are almost 25 percent of people living in poverty. Even though we don’t see it, we know it is there by looking at the data.”

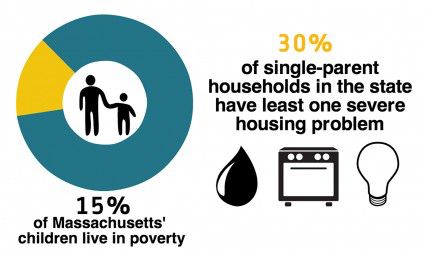

In Massachusetts, Hampden County has the highest percentage of children in poverty, with 31 percent or about 32,260 children living in those conditions. Norfolk County has eight percent, or about 11,861 children living in poverty, giving it the lowest child poverty rates in the state. Overall, 15 percent of Massachusetts’ children live in poverty.

Of Boston’s neighborhoods, North Dorchester and Roxbury have the highest percentages of child poverty, with 39.2 percent and 46 percent respectively, according to a Health of Boston’s Children report released by the Boston Public Health Commission in 2013.

Roubal said the rising child poverty rates go hand-in-hand with unemployment rates and the cost of living. The authors of the report are looking to change the conversations nationwide from talking about child poverty statistics to talking about solutions.

“We are bringing other people to the table,” she said. “One of our main goals is to bring attention to the social and economic factors behind childhood poverty. We want to be able to give all these kids a fair shot.”

Several residents said child poverty is not a noticeable problem in many of Boston’s neighborhoods, but the rising numbers nationwide are disconcerting.

Kiran Reddy, 37, of Beacon Hill, said poverty does exist, but it is more or less prevalent depending on the neighborhood.

“I would imagine that child poverty is present, but there is variation depending on the area,” he said. “Overall, we need to do a better job of taking care of children holistically, but in order to spur change, we must provide children with a good education.”

Lindsey Connors, 26, of Allston, said Boston has strong techniques and initiatives for handling poverty, but there are other cities where poverty may be a larger issue.

“Poverty definitely exists, but I wouldn’t say it’s as prevalent here as in other cities,” she said. “It’s there, but you don’t really see it as much.”

Sarah Whitlock, 42, of Back Bay, said it is easy to forget about the poverty found in other neighborhoods, cities and counties, and it is an issue that lawmakers and community groups should be looking to improve.

“Living in Back Bay, I don’t really see a lot of it,” she said. “Every now and then, I’ll see someone outside of a T stop or on a street corner, but it’s a very big issue. I do believe it’s widespread outside of our little bubble.”