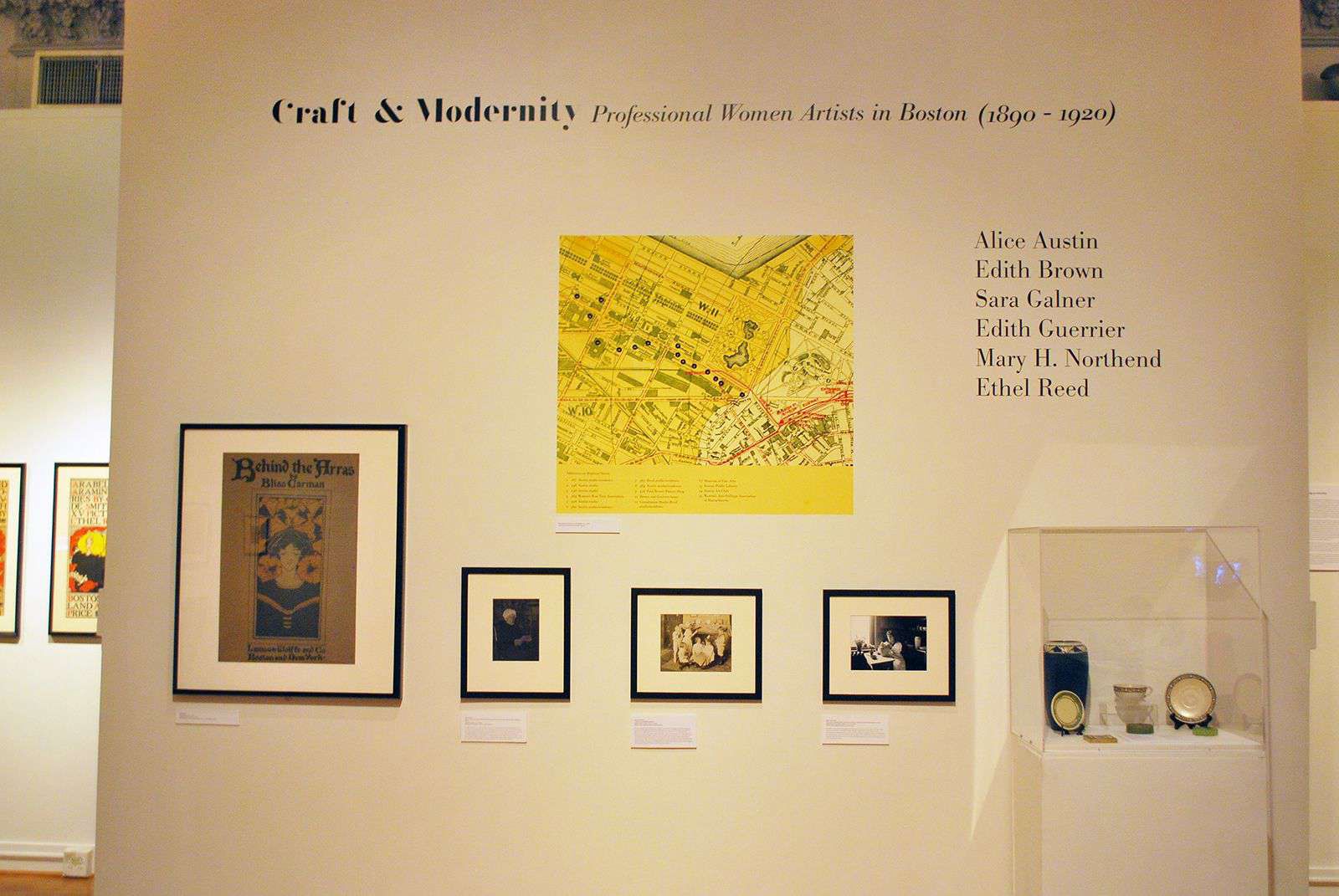

Caroline Riley, a Ph.D. candidate of history of art and architecture at Boston University, has taken her curatorial opportunity provided by the Jan and Warren Adelson Fellowship in American Art to create the BU Art Gallery’s latest installation, “Craft & Modernity: Professional Women Artists in Boston (1890-1920).”

This wonderfully insightful exhibition consists of 147 pieces of various mediums crafted by six illustrious women working in Boston during the height of the Arts and Crafts movement in the late 19th century and early 20th century: Ethel Reed, Alice Austin, Edith Brown, Sara Galner, Edith Guerrier and Mary Northend.

“I want the public to come away from the exhibition thinking about why it’s important to see these works in person,” Riley said.

At the turn of the 20th century, American life was characterized in pushes for reform in areas such as industrialization, immigration and the role of women in society. The Arts and Crafts movement became a vehicle to directly challenge the mechanization of the workplace, as well as address other national concerns through the resultant artwork itself. “Craft & Modernity” takes the nationwide Arts and Crafts movement and centralizes it within the city of Boston.

“As one of the nation’s leading centers of intellectual thought, social activism and artistic creation at the time, Boston serves as an ideal community for a case study of the tangible effects of Arts and Crafts ideologies and other reform initiatives on the everyday lives of real people,” said Nonie Gadsden, senior decorative arts curator for American art at the Museum of Fine Arts, in the exhibition’s catalog.

Given the movement’s emphasis on equality, women were especially given a rare opportunity to involve themselves in social reform. Thus, the exhibition brilliantly combines women artists and historical Boston — namely Boylston Street, between the Boston Common and the Boston Public Garden — where all six women made strides in the arts community.

Riley’s exhibition begins with Ethel Reed, a prominent illustrator best known for her vibrant posters, book covers and endpapers. “Craft & Modernity” features one of her more famous posters for Gertrude Smith’s “The Arabella and Araminta Stories.” Reed uses a minimal color selection chiefly consisting of red, black and white to create a strong and memorable image dominated by beautiful poppies.

On the adjacent wall hangs a stunning portrait of Mary Perkins Olmsted by Alice Austin. It is a platinum print — an image that is embedded in the fibers of the paper and provides a wide range of subtle gray tones. The hushed hues and soft edges of the photo reveal the unmistakable, quiet intelligence of the sitter in a way that is hard to come by in modern photography.

Mary Northend thought of herself as a writer, but proves to be an incredibly talented photographer in her work throughout the exhibit. Her publications primarily focused on colonial architecture and décor, and she used her own photographs to illustrate her texts. One set of photos shows a single room in a colonial home accented with both Greek and Victorian furnishings and decorations — a sophisticated combination Northend was known to promote.

Boston’s Paul Revere Pottery received contributions from Edith Brown, Edith Guerrier and Sara Galner. The workshop produced wares between 1908 and 1942 in and around Boston. The exhibition displays many intricate tableware pieces, vases and tiles. Brown and Guerrier co-directed the pottery workshop with the help of sponsor Helen Storrow, while Galner decorated the pieces.

A favored feature of the exhibition is a side-by-side comparison of the books containing the women’s artwork — the most effective means of making ends meet at the time — and the art by itself. While Austin’s photos were displayed in exhibitions like this one, many of Northend’s were only seen in her publications.

Part of the importance of displaying the women’s art of this movement lies in its didactic nature. Each woman crafted an individual persona as a means to teach her audience various values, Riley wrote in her essay, “Meeting on Boylston Street,” in the exhibition’s catalog. These women identified themselves not only as artists, but also as educators, teachers, designers, shopkeepers, advocates or muses.

With such limited information available about these pioneering women, “Craft & Modernity” serves as a bridge between past and present.

“[The women] changed the meaning of childhood and the home as they simultaneously altered their community’s expectation of their gender,” Riley wrote.

Josh Buckno, associate director of the BU Art Gallery, said he strongly believes in Riley’s chosen subject matter and how valuable it is to display the art “in a way that tells the story it needs to tell.”

And many of the lessons these six women sought to teach in their era apply to the present day. Their art raises questions concerning both national issues, such as independence, individualism and equality, as well as the more private matters such as familial relationships.

Riley and Buckno’s collaborative effort to create a cohesive and aesthetically pleasing space enables Bostonians to learn about their city’s roots in both the Arts and Crafts and the early women’s rights movements through the lens of professional women artists. It is a privilege to be given this historical insight by way of such beautiful works of art.

“Craft & Modernity: Professional Women Artists in Boston (1890-1920)” will be on display from Nov. 7 through Dec. 19 in the BU Art Gallery located in The Faye G., Jo and James Stone Gallery on the first floor of the College of Fine Arts at 855 Commonwealth Ave. For more information, visit the BU Art Gallery website.