A healthy distance of approximately 150 million kilometers separates the Sun and Earth, according to Universe Today. For the two intergalactic spheres, this gap provides just enough coziness. But certain cosmic forecasts, specifically solar storms, can make for a rocky relationship.

“The sun has, as you may know, an 11-year cycle by which it goes through maxima in activity, which we usually represent by counting sunspots. We’re in that maximum period right now,” said Dr. Joshua Semeter, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering at Boston University and associate director of the BU Center for Space Physics.

This current, active state suggests the sun will shoot off a series of solar storms in the coming months. And the most recent storm on Sept. 12 just so happened to select Earth as its target, where it struck at approximately 9:55 a.m., according to The Boston Globe.

“They [solar storms] can go in any direction really,” said Dr. Philip Muirhead, an assistant professor of astronomy at BU. “This one happened to be pointed straight at us.”

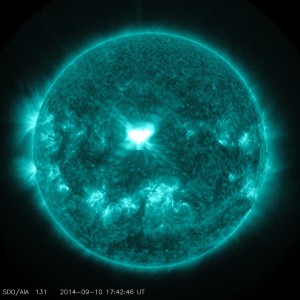

Muirhead said this storm was a bit stronger than most. Astronomers observed what is known as an “X-class flare,” or an exceptional increase in brightness on a specific area of the sun. These storms can form from a number of solar factors regarding the nature of the sun and its grasp on the “blue marble.”

“The solar atmosphere, we like to think of it as sort of a red or yellow ball in the sky. But its atmosphere is actually extending even all the way to earth,” Semeter said. “I make the analogy sometimes to a simmering stew where there’s a vapor coming off from the pot, but embedded in the stew are little bubbles.”

Formally called “coronal mass ejections,” these bubbles fly off into space and travel forward until they stumble upon something to zap. They’re almost like storm clouds, only more intimidating. During the storm on Sept. 12, three of these storm clouds were present.

“So what’s coming at us is this inseparable mixture of plasma and magnetic field, and it’s just sort of expanding all the way to the Earth,” Semeter said.

But with this imagery in mind, why didn’t flaming objects start falling from the sky?

Fortunately, the Earth’s magnetic field does a good job of keeping such science fiction fictional. When this blob of particles reaches Earth, a shielding effect occurs, which is what happened during this storm.

“It turns out that magnetic fields don’t like to mix with one another when they’re in certain orientations,” Semeter said. “It’s basically the same system that’s happening with this coronal mass ejection [from the Sept. 12 storm] and the way it interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field. Current systems are set up that try to shield the magnetized plasma in that object from the Earth.”

But some particles and magnetic plasma do enter the Earth’s atmosphere if the storm is strong enough. When this happens, magnetic displays such as the northern lights become visible in places further south than where such displays are normally visible.

“Aurora [a natural light display] tells us about the properties of these coronal mass ejections,” Muirhead said. “Unfortunately, the aurora is difficult to see when you have a lot of light pollution, so I don’t know of anyone that was able to see it in the city of Boston.”

The recent storm did produce some low-latitude aurora, Semeter said. Although BU students couldn’t observe this vibrant display, inhabitants of western and northern Massachusetts could.

“Not so much right over Boston, but a little bit north over Acadia National Park [in Maine] and so forth, there were some really nice auroral displays,” Semeter said.

BU scientists and engineers plan on keeping their eyes on the star at the center of our solar system — and with good reason. Stronger zaps from the Sun have the potential to damage Earth’s manmade systems, such as GPS, satellites and even continental power grids.

“The part that interacts with the Earth’s magnetic field produces all kinds of effects that are quite interesting and possibly detrimental to society,” Semeter said. “It’s sort of like predicting the weather. It’s really difficult sometimes to tell.”