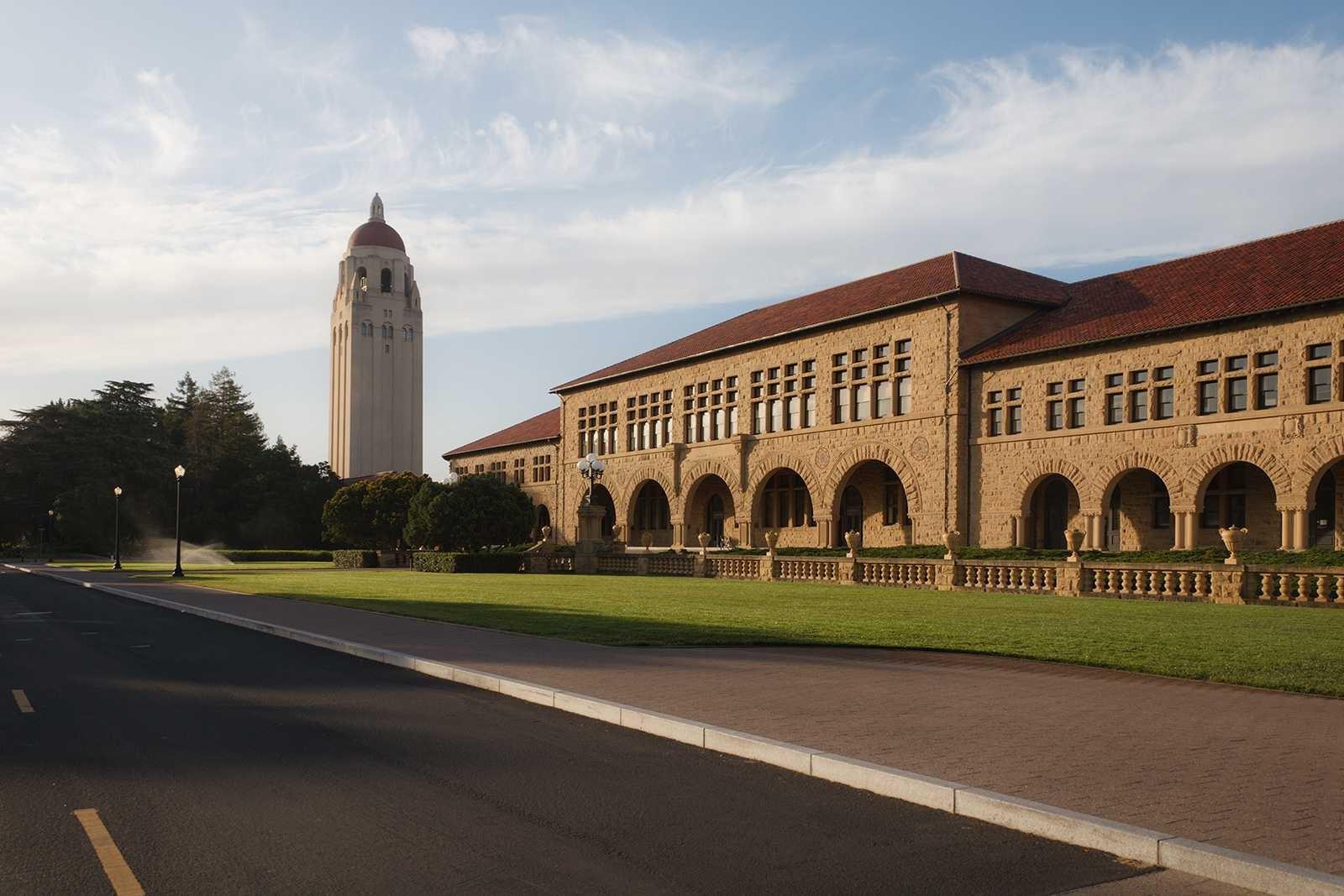

With college admissions getting more and more selective, inevitably, more and more students will receive the dreaded apology letter that comes with a rejection from their choice university. It’s no secret that students these days are more motivated than ever to make themselves as attractive as possible to schools. So with a pool of straight-A applicants (all with a hefty dose of leadership roles, of course), how does a school decide who is admitted, who is waitlisted and who is flat-out rejected? That’s what four Stanford University students set out to find out. And they achieved it.

It’s a law called the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974, or FERPA, and it stipulates that any student has a right to access their educational records. FERPA also states that the records must be made available to the student within 45 days of the request, or the school risks losing its federal funding.

But now, these students, who run the anonymous newsletter The Fountain Hopper, are reading the law in a new light, focusing on the rights it gives them as students to see their college application results and recommendation letters. The Fountain Hopper has made a name for itself writing about news pertinent to college students with an irreverent tone, and now it has made a name for itself as the paper that exposed FERPA’s most interesting and controversial loophole.

The Fountain Hopper reported that students have received written assessments from admissions officers, numerical scores that were assigned to their applications (at Stanford, it’s on a system of 1–5), and even recommendation letters written by high school teachers and guidance counselors. One student, who asked The New York Times to remain anonymous, said he received a packet consisting of 700 pages, including a log of every time his electronic identification card had been used to unlock a door.

While only those who are actually enrolled at Stanford can see their records — applicants who were rejected cannot see why they were turned down — other colleges could choose to release information for all applicants, despite their admittance result. The students at Fountain Hopper told the Times they hope their actions will inspire students at other colleges, which may not have this same “students-only” rule that Stanford does. This could allow rejected students to see why they were rejected from a university, instead of just the quick ego boost Stanford supplies.

This total transparency in admissions could be a good thing. Most students would probably love seeing what admissions counselors had to say about them. Humans are curious by nature, and if you’re only viewing your individual records, you aren’t hurting anyone but yourself. It’s dangerous to have no idea what conditions colleges are accepting or denying people on, especially as the applicant pool gets more homogenized at top-tier universities. Distinctions are made, but it’s not exactly clear where.

But realistically, using the language in FERPA to see college application results takes away the purpose of a fair application system. Teachers write recommendation letters keeping in mind that the student is likely never going to see what they wrote. If they were suddenly afraid that students were going to ask for their educational records and see their commentary, it would take much of the fairness and anonymity out of the recommendation process.

Of course, the admissions process should be honest and transparent. But all this new reading of the law really does at best is create petty annoyances about something that’s already over and done with. And at worst, it could allow students who were accepted at top-tier universities to sell their application materials to students applying to other schools to copy, or at least use as a model, which would be unfair.

Admissions officers should not have it in the back of their minds that someday, students could see their records. By keeping this process confidential, it can carry on in the (mostly) successful way it has been for decades.