There are about 2.5 million people of Indian descent living in the United States today. While India’s rich food and dance are celebrated in America, the caste system which Indian emigrants came from is often forgotten, according to award-winning WGBH journalist Phillip Martin.

There are about 2.5 million people of Indian descent living in the United States today. While India’s rich food and dance are celebrated in America, the caste system which Indian emigrants came from is often forgotten, according to award-winning WGBH journalist Phillip Martin.

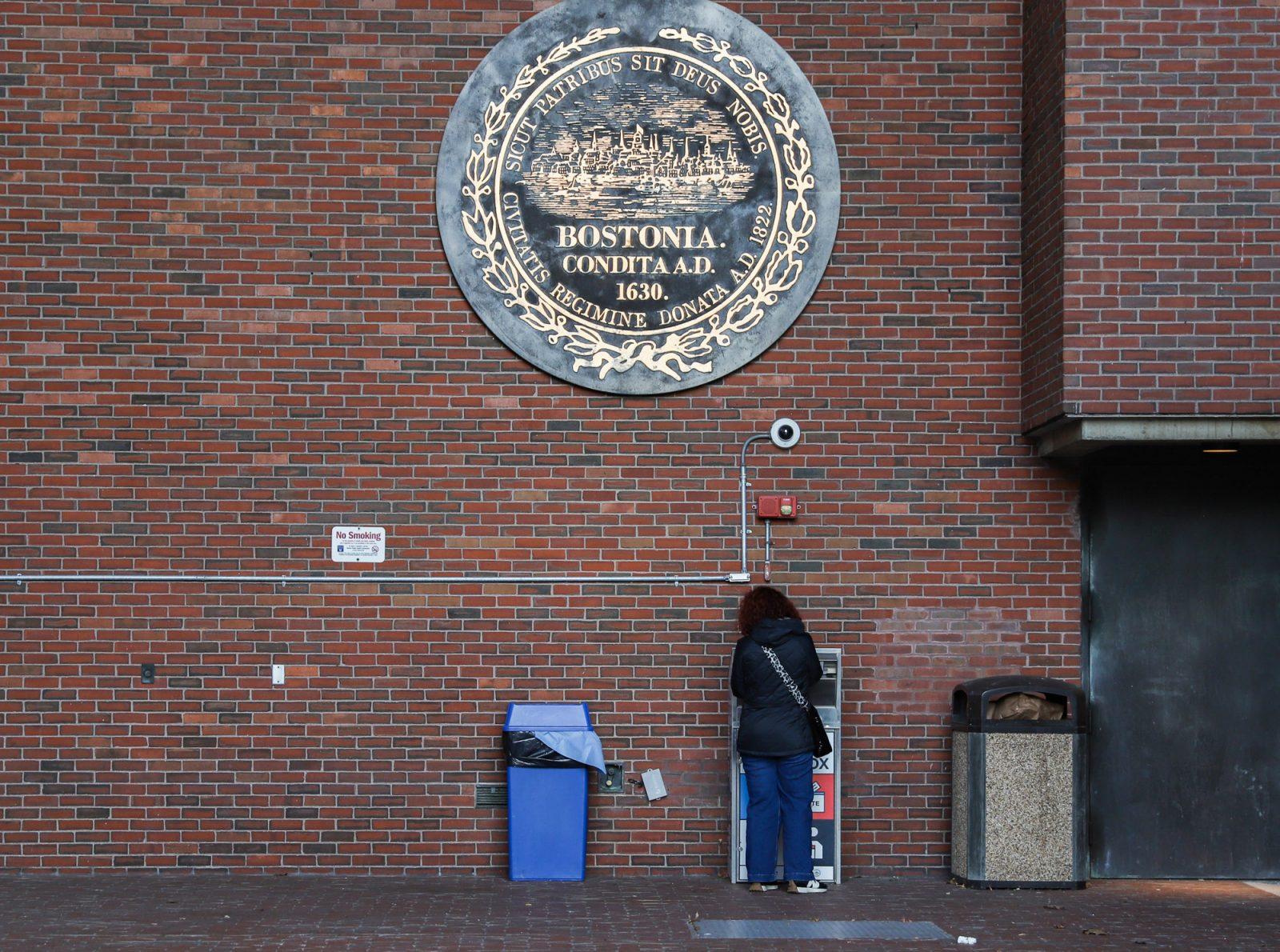

This ignorance about the caste system inspired the panel discussion Martin led on discrimination Indian immigrants face, he said. Held Thursday at the WGBH Studio in the Boston Public Library, the panel was part of Martin’s most recent series called “Caste in America.”

Martin began the panel discussion by defining caste as Indians’ social hierarchy that is determined by birth.

Kavita Pillay, a documentary filmmaker and reporter for Public Radio International’s “The World,” was one of five panelists at the discussion. She said while many Indian immigrants are disadvantaged once they move to the United States, most come from upper castes who are privileged enough to have the opportunity to resettle in a different country.

“I know how my parents came here — with one suitcase and a handful of dollars — and the vast majority of my Indian American friends also have similar stories,” Pillay said. “But we make it seem like it started like that. I felt it was important to muddle that I am both privileged and marginalized.”

The sentiment of two sides, an us-versus-them mentality, is not an uncommon phenomenon in the United States, which is home to a melting pot of racial and cultural backgrounds.

Another panelist, Suraj Yengde, is India’s first Dalit — a member of the lowest-ranking caste in India — to hold a doctorate from a university in Africa. Yengde said he believes the diversity of American society tends to create false categorizations when it comes to the topic of race.

“In the 1970s, we see an era where more regional representation is being discussed where we have Asian Americans, African Americans and on and on,” Yengde said. “Again this is a generalized way of looking at African Americans, there are many other categories that exist among African Americans, too, and they have their own unique histories.”

He said there are many similarities between the identity struggles of African Americans and those of Indian Americans from lower castes.

Panelists discussed parallels between policies such as affirmative action and India’s reservation system, a constitutionally mandated quota for college admissions and government jobs for those of the Dalit caste.

However, the panelists discussed that once immigrants come to America, they aren’t seen as part of any one caste system — just as Indian.

“A gunman murdered two Indian men in the Midwest, and I don’t think he asked, ‘Are you Dalit, or are you Brahmin?’,” Martin said. “He shot to death two men he saw as outsiders. That becomes the context for many Americans, that you are other.”

Ramesh Nallavolu, an Indian American attendee from Boston, said many Indian Americans today are worried about introducing a conversation regarding caste to the United States.

“I’ve been in the U.S. for 20 years. I have not experienced any caste-related discrimination, and no one asks me what my caste is,” Nallavolu said. “I have two kids. I never talk about caste with them, they don’t know anything about it.”

Panelist Swami Venkataraman, a member of the National Leadership Council of the Hindu American Foundation, said Nallavolu’s kids may not even need to discuss the issue of caste all together. Venkataraman discussed how he believes caste is not a systemic issue in the U.S. and that the “awareness of caste ends with the generation that comes into this country.”

Laurence Simon, a panelist and professor of international development at Brandeis University, said he thinks the solution to discrimination is not to dissolve the topic of caste, but to place a greater emphasis on it in educational curriculums.

“The reason they [women’s studies courses] began to be developed in the U.S. is because women got fed up studying history with very little reference to women,” Simon said. “If women are invisible in the curriculum, then they don’t count — the point here being that if caste is not part of the history taught in American universities, then they don’t count.”

Twenty-four percent of Boston University’s current freshman class are international students, and India is one of the five countries with the highest numbers of international students. Yengde said he looks forward to the day when universities, such as BU, embrace and recognize Indian students with different backgrounds.

“American institutions are these reservoirs and preservers of knowledge,” Yengde said, “and I think with the student movement, caste struggle will be next.”