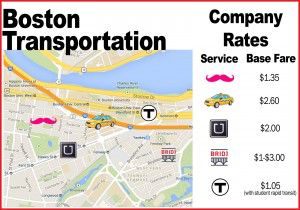

These companies, and other similar brands, are keen to expand their user bases by offering ridesharing services at competitive prices. With a rapidly changing landscape in which services are vying for the same customers, private and public transportation companies have to reorient themselves accordingly.

But this was not always the case. The transportation industry was relatively untouched until 2009, when Uber entered the marketplace.

“To be honest, I did not know any other taxi place or taxi company except for Uber. That’s the reason I got into this,” said Hem Grabyal, an Uber driver.

Uber is worth $17 billion, according to a statement released by Uber in June. A May 27 blog post on the company’s website indicated that Uber creates 20,000 new jobs per month.

With an increase in funding and recognition in the years since the company’s launch, Uber has decreased emphasis on incentives for driver referrals, Grabyal said. Uber used to employ stronger incentives for drivers to refer their friends as prospective drivers, but the incentive model has changed now that the company is comfortably backed by top-tier investors.

“Before, they used to give us $200 or $300 just to refer a friend, and when he joins Uber and starts driving and he drives for certain hours and certain destinations…” Grabyal said. “But now I think they are giving us $50. Now I see there are more and more Uber drivers. More drivers, more competition…They [Uber] say there are going to be more riders, but I haven’t felt anything yet.”

Lyft, which operates in 65 cities, compared to Uber’s 128, is eager to cut into Uber’s market share. Lyft spokeswoman Katy Daly said the ridesharing company raised $250 million in April, bringing total funding to $333 million.

Although their prices are often lower than those of their competing local taxi companies, Uber and Lyft are not often used as daily transportation services. A ride with Uber, for example, costs $8.86 for a 2.93-mile Saturday morning trip, while a Friday evening trip of 2.26 miles runs a steep $18.48. Many still turn to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority for daily transportation needs.

But perhaps there’s another option.

Bridj, a Cambridge-based transit company that beta launched on June 2, operates in Allston, Brookline, downtown Boston, South Boston and Cambridge, said Ryan Kelly, Bridj marketing manager.

Bridj is a shuttle transit service with a few different routes throughout the city. Because the service is still in the beta stage, buses are only available on weekday mornings. Customers can access the week’s schedule through Bridj’s website and purchase tickets for either an individual day or for a week at a reduced rate. Through a combination of publicly available data as well as user provided information about where people live and work, Bridj aims to create specialized routes based on consumer need.

“We’re trying to create the world’s first smart transit system,” Kelly said.

Rather than a substitute for the MBTA, Bridj looks to serve as a complementary service, said Kelly. The company’s launchers hope to make their system a daily transit option.

“Things like rail lines, like the Green Line or the Red Line or the Orange Line, those routes were planned,” he said. “Boston [has] one of the oldest transit systems in America, and those tracks were laid down probably more than 100 years ago.

“I used to live in Coolidge Corner and commute to Kendall Square. That trip would honestly take about…45 minutes to an hour every day on public transit,” he said. “You had to go all the way into Park Street [Station] and go back out to Kendall. It’s one of the big reasons my wife and I moved out of Brookline into Cambridge. And from Coolidge Corner to Harvard, she only had a bus that made about 15 stops between her pickup location and destination.”

Kelly said the main reason Bridj cannot be a complete substitute for the MBTA is because of the difficulties the company may encounter with scalability.

“We see ourselves as a more nimble option and as a complement to an existing transit because we cannot expand necessarily to everywhere the T wants to go,” he said.

Pricing determination is an issue for Bridj, especially since the company offers indulgent amenities such as WiFi and comfortable seating.

“The [MBTA] transit system is heavily subsidized by the state government. The actual cost is much higher than $2.50. But on the other spectrum, you have the option of taking a taxi or driving yourself,” Kelly said. “We think we are going to be in the middle of that. It may be a little more than taking the subway but less than taking a taxi or driving yourself. Our beta pricing is extremely accessible. Trips are as low as $1, and the highest trip is $3.”

Similarly, scalability has been an issue for some Uber drivers, Grabyal said. An increase in the quantity of users, coupled with surge pricing, would imply that Uber could profit more and pay drivers more. However, to lower costs, Uber pays employees less, Grabyal said.

“Compared to how much we made before, now we make less on the same distance, so that’s kind of hurting,” he said. “Uber says there will be more quantity because there will be more people coming and using Uber, so I don’t know how true that is because I don’t see much difference. I see the same number of people coming in as before.”

Kevin Mannix, a College of Engineering senior who has taken Bridj twice during the summer to commute to his internship in downtown Boston, said competition is needed to spur better services.

“It’s an industry that obviously everybody has the experience with,” Mannix said. “These transportation services are doing a great thing either by spurring public transportation to be better or by providing an alternative, better away to be transported around the city.”