David Alexander, a scientist at the University of Kansas and the author of “On the Wing: Insects, Pterosaurs, Birds, Bats and the Evolution of Animal Flight,” always had an interest in flight. His father worked for the Air Force and Alexander grew up in Dayton, Ohio — home of the famed airplane inventors and legends the Wright brothers.

Throughout his childhood, Alexander dedicated much of this time to building model planes, including some that could actually fly.

“There are two strings going out to the airplane and they come into a handle,” Alexander said. “You hold that and it flies around you and you turn in a circle. They were fun when I was a kid.”

Although he has a whole basement full of radio-controlled planes that he still flies, Alexander said his focus is now on the scholarly side of flight in the animal kingdom. His foray into authorship began with his 2002 publication, “Nature’s Flyers: Birds, Insects, and the Biomechanics of Flight.”

“That was my attempt to cover all of the important aspects of the biology of flight,” Alexander said.

“Nature’s Flyers” included a chapter on the evolution of flight, which Alexander delves into more deeply in his latest book. “On the Wing” fills in what Alexander saw as a surprisingly “empty niche” in the literature on the evolution of animal flight.

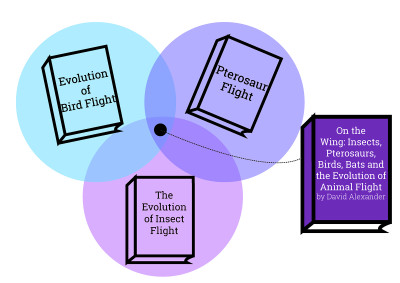

“There are books out there about evolution of bird flight, and there are books out there about the evolution of pterosaur flight,” Alexander said. “There is a really good book on the evolution of insect flight, but it’s a little on the old side now. But there is not one book that looks at them all together.”

Alexander said he believes that the lack of a united source on animal flight stems from biology specialization. Most biologists are only familiar enough with one species to write books about. Alexander himself is an insect expert, but he is fortunate enough to have colleagues at KU who are top bird and pterosaur experts. Alexander said he could turn to them for second opinions on his research, giving him the unique opportunity to write confidently about different animal groups.

Birds were a particularly interesting group to Alexander because the details of their evolution have been contested among scientists over the years. Although no longer a matter of debate in the scientific community, Alexander said that the average person might not be aware of the fact that birds are descended from dinosaurs.

“To a paleontologist, a bird is just a small feathered dinosaur,” Alexander said, “because if you look at who they’re most closely related to, it’s now pretty much indisputable that birds evolved from small meat-eating dinosaurs.”

“To a paleontologist, a bird is just a small feathered dinosaur,” Alexander said, “because if you look at who they’re most closely related to, it’s now pretty much indisputable that birds evolved from small meat-eating dinosaurs.”

Instead, there have been debates over whether birds were gliders or runners before becoming flyers. In “On the Wing,” Alexander argues for the former.

“The original primitive birds that first started becoming aerial did not look like roadrunners,” Alexander said. “They probably looked more like sparrows.”

Other animals, Alexander said, never evolved beyond gliding. Some such gliders, such as flying squirrels and flying fish, are familiar to us because they live in North America.

There are interesting gliders elsewhere, however, such as the flying frogs of Asia and South America that use their large, webbed feet to glide between branches. There are also the flying dragon lizards of Southeast Asia that have extendable ribs that they project to make half moon-shaped wings on their sides.

Perhaps most fascinating of all are the gliding snakes, which live in very tall Asian rainforests. These snakes glide by flattening their bodies and throwing them into s-curves. Each curve acts like a wing, so a snake can glide with several makeshift wings at once.

“They can glide at a 30-degree angle, which is a whole lot better than a person jumping out [of] a plane,” Alexander said.

For those not intrinsically captivated by the air travel of strange flying snakes, let alone the everyday sparrow, “On the Wing” could still be a valuable read for other reasons.

It appears that the ability to fly might be key to the domination of insects, birds and bats in the animal kingdom, disregarding the pterosaur. For example, there are more insect species in the world than all other animals combined, and 98 percent of them have wings.

“Of these groups, the three that are still around, they are in some ways particularly successful examples of their kind of animal,” Alexander said. “So if you want to think about it from the perspective of why should I care about flight, well, it looks like flight is why these animals are so common and so successful as they are.”