Columbia University professor Tey Meadow recalled meeting Rafe, one of the research subjects in her new book “Trans Kids: Being Gendered in the Twenty-First Century,” as a young girl demonstrating a dance move from a Britney Spears video.

The book explores the changing attitudes of parents toward transgender children and the cultural shifts that come along with them, according to Meadow.

“It was evident that what was on display was far more than a performance of sexuality,” Meadow said. “Some core part of the being that was Rafe was deeply and essentially feminine.”

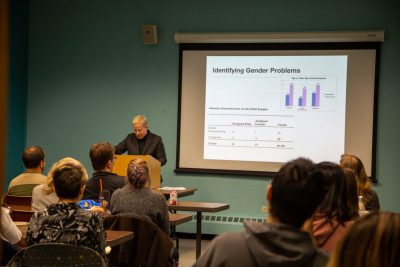

Meadow discussed her research that followed dozens of families of transgender children as a part of the Boston University Department of Sociology’s seminar series Monday.

Deborah Carr, professor and chair of BU’s Department of Sociology, said she helped to organize the event.

“The number of young people who are identifying as gender nonconforming has been increasing,” Carr said. “It raises all sorts of questions about how parents should interact with their children, how schools should respond, policy should respond.”

Carr said she believes research is crucial to help meet needs of transgender children and their families.

“She is doing such cutting edge research on a topic of tremendous and increasing importance,” she said.

The department chair said that while reading Meadow’s book, she was fascinated by parents’ reactions to the choices they faced and their difficulty understanding gender-fluidity.

Casey Ramos, a sophomore in College of Communication studying film and television, recalled having past experiences with transgender and genderfluid friends.

“[My friend] identified as genderfluid, and her mom was like, ‘Absolutely not — you are my daughter. You are not they, you are she,’” Ramos said. “Pronouns and name changes are really jarring for parents because [they’ve] called [their children] this all [their] life.”

Meadow said she believes that despite increased acceptance of gender-fluidity, gender is becoming more particular. The specification is infiltrating social and academic institutions and the legal system.

“What’s happening is that the language we use when we’re talking about gender is becoming more complex,” Meadow said in an interview. “The options that people have for describing themselves, for embodying different forms of gender identities, are proliferating and becoming more precise, not less.”

According to Meadow, one of the book’s main points is that gender non-conforming behavior that once lead to efforts by parents to snuff it out now cause parents to realize that their children possess a different identity than the sex they were assigned at birth.

“Now, gender non-conformity is not merely seen as a failure of gender, it can also be seen as a different form of gender,” Meadow said.

The author said she believed this pattern is a part of a recent increase in trans acceptance. She spoke about how schools, hospitals, gender clinics and other social institutions are becoming increasingly attuned to questions of gender, and how resources for parents, clinicians and children have grown.

“Gender is no longer just an identity, but an industry,” Meadow said.

Despite this growth, however, Meadow explained her research found that parents who were accepting of their trans children’s identity still faced difficulty.

While working with medical professionals to navigate puberty and transitioning, many parents in Meadow’s study faced various challenges, all amplified by the pressure of time. One family she worked with described feeling pressure to make decisions about their child’s gender before puberty.

“On the one hand, [parents] feared the unknown long-term consequences of hormones, and on the other, they had copious evidence suggesting previous generations of trans adults suffered mightily when their bodies and identities didn’t match,” Meadow said.

Parents found some relief from the pressure that many felt in efforts to standardize medical care for transgender children, Meadow said. Global efforts have lead to increasing amounts of data on children’s identifications, social experiences, family relationships and peer interactions.

“The prevalence of research on the topic … is just exploding,” Meadow said.

Despite seeing changes in parents’ attitudes and in the medical field, Meadow said she still sees weaknesses in other parts of the social climate.

“We’ve been trained by psychologists to move very quickly from thinking that a child might be transgender to wondering if it’s possible for them to not be,” Meadow said.

Meadow recalled speaking with another researcher and asking him if gender adaptation could ever be positive.

“When I said that to him, my eyes welled up with tears, and I realized that this thing happens with psychologists where we believe they can tell us things about ourselves, and we believe that they know somehow,” Meadow said.

The author said that despite the the threat of the current political climate and Trump’s recent move towards defining gender through biology at birth, it does not negate the progress already made.

“What does it mean that someone like Donald Trump, with his politics, is actually interacting with this subject in such a disgusting way? It means something’s been accomplished. The contestation is a part of the progress,” Meadow said. “The arc of history may bend towards justice, but that doesn’t mean that it’s a smooth bend. It’s more like a rollercoaster.”