Yesterday, I took the time to cut and paint my nails. They were chipped and ragged, bitten and picked on like a bone. It’s a vivid, disgusting image, I know, and it’s an old habit I thought I had kicked.

But, of course, it would be 2020 when I rediscover my weird habits.

Most of them are much less gross than my nail hygiene: twisting my school ring until the logo is centered with my knuckle and then tapping my knuckle until it feels just right. I also play with my hair, fidget with my clothes, bounce my legs and crack my fingers and back.

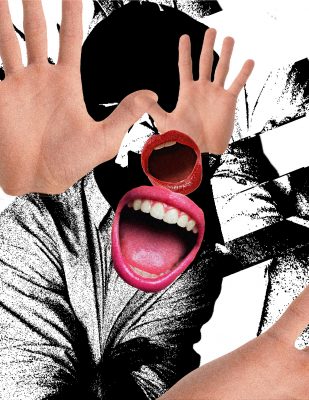

I feel as if our little behaviors and microexpressions are often lost in a world dominated by digital communication. If anything, this is exacerbated by the amount of time we’ve spent isolated in our living spaces.

We get so involved in our work and ourselves that it takes either a strong empath or a hyper-observant person to notice when a friend is trying to hide their descent into a breakdown.

In order to truly understand and connect with someone, we have to use multiple languages and methods of communication. We have verbal and written communication, which is a given, as well as body language. By paying attention to body language, we automatically notice — and can even learn to “read” — someone’s facial expressions, posture, gestures, eye movement, voice and touch.

Body language and behavior are crucial for human connection and communication. To an extent, we subconsciously notice and process information from another person’s mannerisms. This presents itself in a gut feeling or a “vibe” that either tells you, “yes, they’re trustworthy” or “get the hell out.”

The saying “trust your gut” comes from this. But your gut is really just your brain analyzing and recognizing patterns of behavior. Body language is one of the many pieces of data that allows your brain to form a framework that can predict and process information.

Another form of communication is love language. Your love language — acts of service, physical touch, words of affirmation, quality time or receiving gifts — is how you primarily express affection. The most important aspect of this communication is speaking in your partner’s love language rather than your own, which takes conscious effort.

Although body language is subconscious and love language is intuitive, both can be learned. By building on top of both languages, you can notice when something is off or when someone is struggling without them having to tell you.

I call this “distress language.” Of course, it’s more a combination of languages than its own new thing, and distress has no clear categories like love does.

However, we do have categories of common stress reactions. The New York State Office of Mental Health categorizes common stress reactions as behavioral, social, physical, cognitive or emotional.

Knowing someone’s distress language is understanding whether they want to talk or simply need your company. It’s knowing whether they’re more withdrawn or outgoing when they’re stressed. It’s knowing what their stress reactors are or which category their stress manifests in, and then responding appropriately.

Digital communication dominates our life, which makes it easy to assume a simple text message or conversation via Instagram direct message is an effective way to check in on our friends. But over a screen, it’s much more difficult to read someone’s body language and know what’s really going on.

Honestly, our instinctive human communication is not something that’s as cut and dried as “pointing your feet toward someone will make you like them” or as restrictive as confining everyone to one love language. Our personal language is constantly shifting — be it love language, stress reactions or otherwise.

In good news, our brain is made for this. We are great at recognizing patterns and adapting to them when they break. Once we learn how to listen, we can tell if someone’s lying, show our partner love and recognize when a friend needs help.

What we should commit ourselves to, then, is simply figuring out how someone talks beyond linguistic boundaries so the signs they send don’t get lost in transmission.