The Asian American and Pacific Islander community struggles with systemic inequity, the model minority myth and openly racist and recent gendered hate crimes, said panelists in a Commonwealth of Massachusetts Asian American Commission town hall meeting Thursday.

Panelists called for representation in government, increased language access in public services, less restrictive immigration policies, Asian American studies curricula in schools and unity with other oppressed minorities.

The online meeting, conducted in English, featured Vietnamese, Cantonese, Mandarin and Spanish interpreters in an effort to fully reach its multicultural audience of roughly 2,000.

Panelist Sharon Cho, a Dorchester resident and project manager at the Dorchester Bay Economic Development Corporation, opened the program with words of remembrance for those killed in the March 16 shooting in Atlanta. Of the eight victims, six were Asian women.

As a child of Atlanta’s Korean immigrant community, Cho said she was “sitting in grief and rage.”

“All of our community, Asian Americans, women, immigrants, refugees, low-wage workers, queer and trans folks and all those who experience violence at the hands of white supremacy, capitalism and misogyny,” Cho said, “we are grieving and we are in pain.”

Angelina Hứa, Dorchester organizer at the Asian American Resource Workshop, said anti-Asian violence isn’t an isolated act, but the resonance of institutional oppression that “gaslights us to believe that violence is normal.”

“Anti-Asian violence is part of larger structural racism that has historically deprived Asian American Pacific Islanders of resources and security,” Hứa said. “Through gentrification, the school-to-prison-to-deportation pipeline, policing, lack of workers’ protection and more.”

Hứa added the violence is “multi-layered,” where boundaries of class, age, gender, immigration status, sexuality and ability intersect.

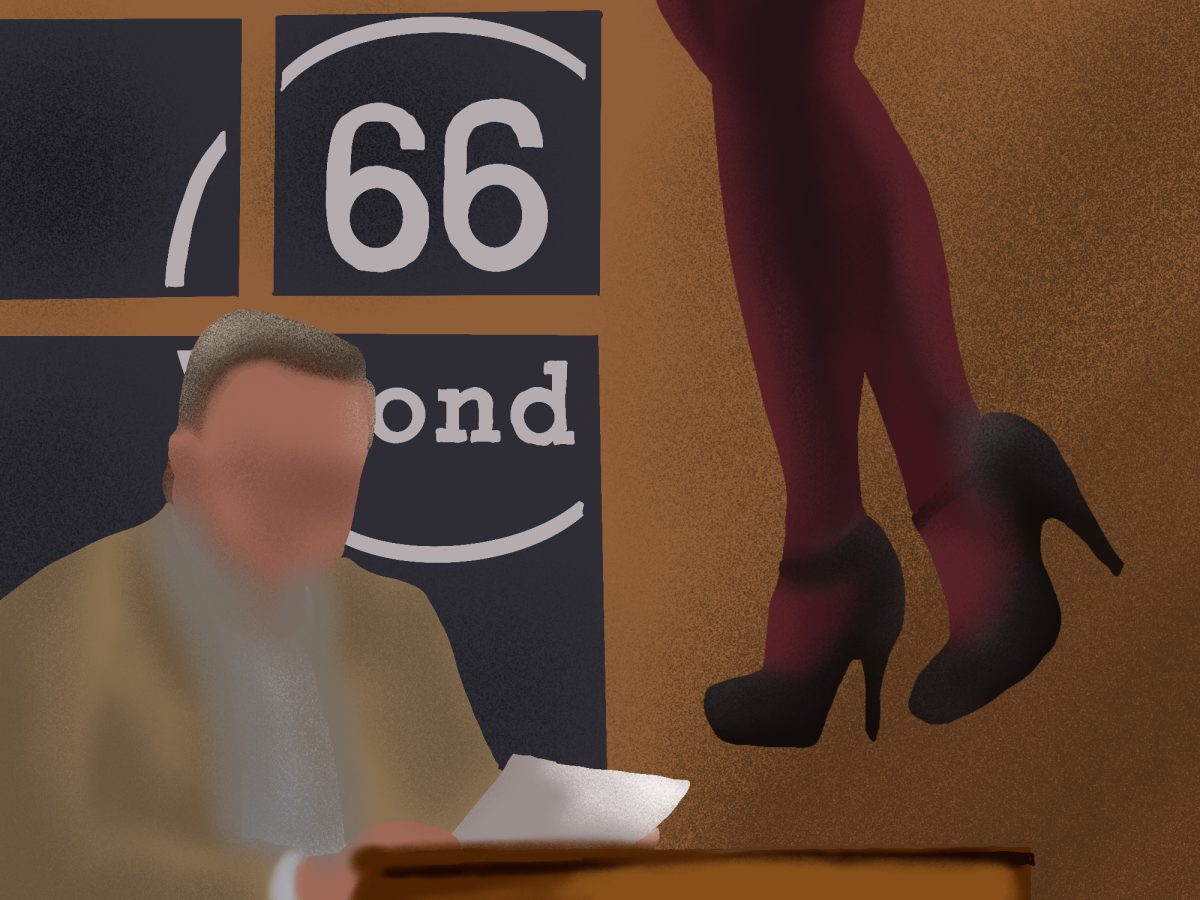

“In Atlanta, a misogynistic white supremacist targeted spas to murder Asian immigrant women workers,” Hứa said, “because this country continues to objectify and dehumanize Asian immigrant women workers as disposable objects for sexual pleasure and profit.”

Thao Ho, a legal and organizing fellow with AARW, said Asian immigrant women working low-wage jobs live in constant fear of deportation and gentrification.

“Just this past month, the Biden administration deported [33] Vietnamese community members from across the nation, in the midst of a global pandemic,” Ho said, “despite a supposed 100-day halt on all deportations.”

When it comes to protection and safety, Ho said police are rarely a trusted resource for members of these communities.

Such was the case, she said, when police arrested a non-English speaking person after his landlord pushed him down the stairs. The arrested man later asked AARW for assistance, Ho said.

“This was because the landlord spoke English, while the tenant could not advocate for himself in English,” Ho said. “This is almost always the case when there is an incident between someone who is not a proficient English speaker and someone who is.”

Bethany Li, director of the Greater Boston Legal Services’ Asian Outreach Unit, said long-term, structural change is the key to improving the health and safety of AAPI communities — not increased law enforcement.

Li said improvements in low-income housing, public education, economic support and language access in government aid would work to make communities safer, adding that often, neighborhood-based programs are those that are relied upon and have an active role in advocacy work.

“What we’ve seen during this pandemic, in this time of crisis, is that the community has turned to the trusted or community organizations time and time again to make sure that they’re safe,” Li said. “It’s community-based organizations who have been on the streets and on the front lines every day, and have to be part of the solution.”

Jean Wu, senior lecturer emerita at Tufts University, said public education often disregards Asian American history. Teaching it alongside other “long-erased” histories would help to create unity among students of different races and ethnicities, she said.

“Only when you look at the experiences of different marginalized groups and oppressed groups together,” Wu said, “can you begin to see how a white supremacist structure works and pits people against one another and keeps things in place.”

One such example of this is the model minority stereotype, Wu said, which was invented to discredit the civil rights movement by using Asian Americans’ economic success as an argument that structural change isn’t needed.

“The model minority is not about Asian Americans as much as it is about a way to discipline other groups and to say ‘We don’t need any change,’” she said.

The myth continues to drive a wedge between Asian Americans and other minorities, Wu added.

Kaye Chin, a sophomore in the College of Arts and Sciences and vice president of external affairs of the Boston University’s Asian Student Union, said in an interview that representation in a learning environment is key, which can be improved by diversifying faculty and staff and Asian American studies courses.

Lack of representation leads to an incomplete picture, she said, evidenced by the Boston University President Robert Brown’s “lukewarm” response to the attacks in Atlanta.

“It basically mentioned the hate crimes and then threw a diversity statement on it,” Chin said. “It just showed how much of a lack of understanding and how not serious the University is taking these attacks.”

Hứa said the most effective tool for fighting the systems of oppression is to work with other oppressed groups.

“We need to collectively imagine, create and cultivate new structures that actually keep us safe, not more policing and incarceration,” they said. “Because it’s either freedom for all of us or none of us.”

The town hall concluded with a summary of statewide policies and legislation the Asian American Commission advocates for.

Among them were bills establishing more detailed racial data collection, increasing language access in government and implementing Asian American studies curricula in public schools.

A previous version of this article misstated that Sharon Cho is a Medford resident. The article has been updated to correct this error.