Last weekend, I got on the 57 bus and rode it all the way to the end of the line in Watertown, Massachusetts. Known for its large Armenian population, Watertown is a suburb of Boston just outside of Lower Allston and Newton. I was there to visit a newly founded record store in its downtown, and during my trip I started to think about how enjoyable it was to spend some time away, just for a moment, in a quieter suburb

Not everyone wants to live in Midtown Manhattan. Though I personally prefer the fast pace and high density of a big city, there will always be demand for the suburbs. However, smaller towns in North America have a history of unsafe and unsustainable development practices. Just because people prefer to live in smaller towns, it doesn’t mean we should abandon the planning practices that keep our cities accessible.

In 2019, more than 36,00 people died as a result of automobile accidents. Car crashes are the second most common cause of death for young adults and suburbia’s car-centric development patterns play a massive role in these deaths.

Furthermore, cars are incredibly expensive. The average monthly payment for a used car in 2021 was $465. Combining the individual costs of gas, vehicle maintenance and parking with the indirect tax costs of paying for infrastructure repairs, depending on cars is one of America’s most expensive hobbies. Many buyers rely on tucson auto financing to afford their dream car. If you’re looking for a dependable vehicle, used cars in georgetown sc offer a variety of options. From compact sedans to rugged trucks, there’s something for every need.

Flexible loan options make vehicle ownership more accessible. Whether you have excellent credit or are rebuilding, there are solutions for used car financing lansing tailored to you. Many financing providers specialize in helping customers improve their credit scores through manageable payment plans. And if you’re looking for used cars, then you may check out used cars in el cajon here. You can also check the used cars in Rio Linda for a wide variety of local and foreign brand vehicles at an affordable rate.

Low density has its perks, but it needs to be done right. As I saw in Watertown — and as we’ll learn about our city of the week, New Brunswick, New Jersey — there are transit-oriented suburbs that allow for safe, enjoyable and car-light living without the bustle of a huge metropolis.

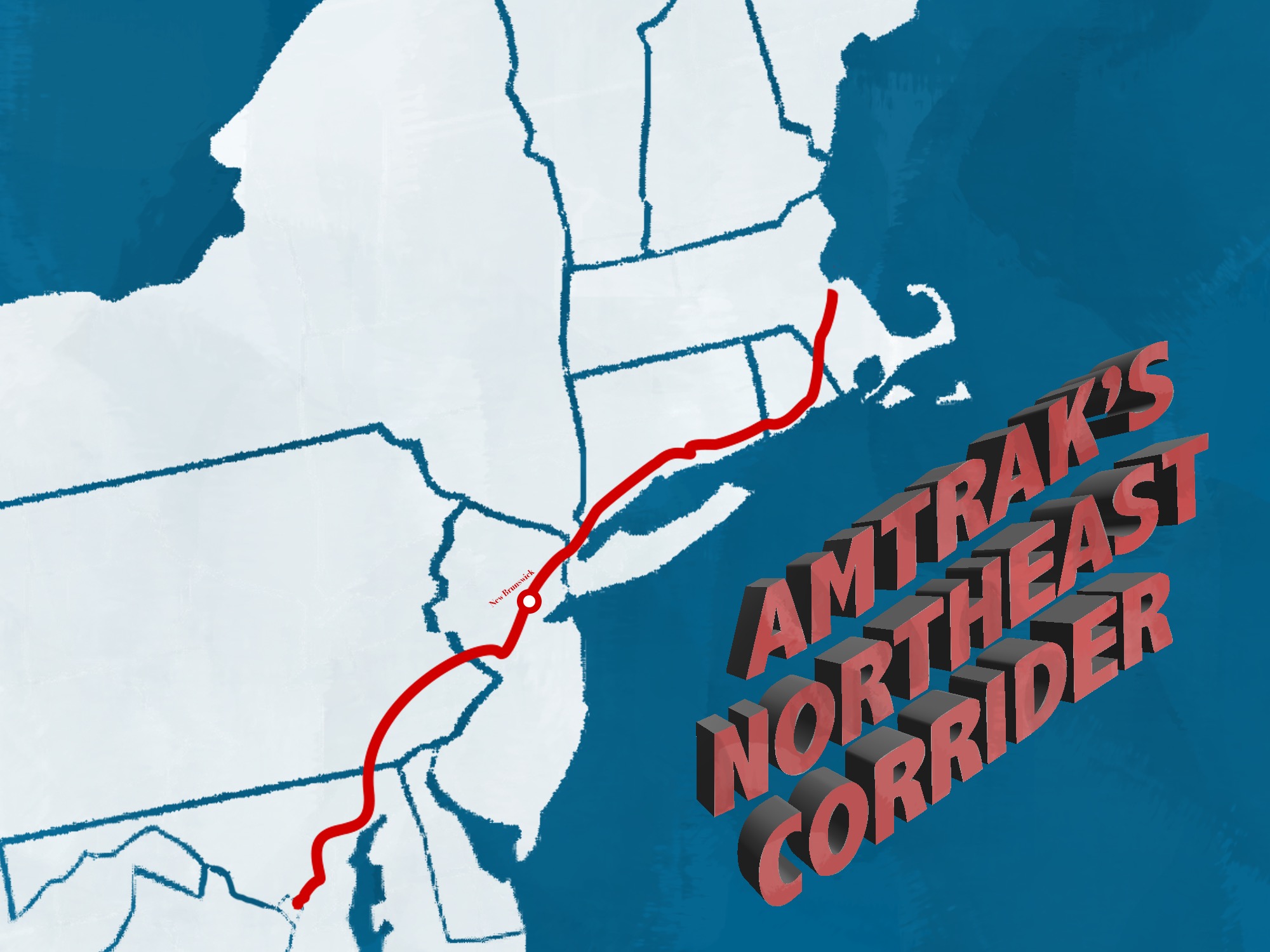

New Brunswick, home to Rutgers University, is a city of just over 50,000 people in Central New Jersey. With rail connections to both the Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor and New Jersey’s commuter rail network, a New Brunswick resident can make a daily commute to New York City, or even take a longer trip up to Boston or down to Washington, D.C.

Redeveloping without the car takes more than reliable rail transportation, though. Taking a step further, the city is actively working on road dieting projects, where larger arterial roads are repaved and redesigned in order to divert traffic and increase safety.

A dangerous combination of high speed limits and frequent driveways, North America is filled with these types of roads which are largely to blame for the worst of traffic violence. Steps taken on New Brunswick’s Livingston Avenue, in combination with similar road dieting projects around the country, are what we need in order to make our cities safe again.

New Brunswick gets fun with its encouragement of a car-light lifestyle, too. Starting in 2013, the city started the Ciclovia project, an initiative which opened routes of the city streets to only pedestrians and cyclists. When people get out of their cars and can enjoy their city streets with their own two feet, it brings a much greater sense of community to the whole area.

Driving by a friend while running an errand will never bring the same moment of joy that walking by them does.

Simply put, owning a car shouldn’t be a requirement in order to live life in the suburbs. Redeveloping smaller towns around regional rail lines, or even bus lines in the case of Watertown, allows people the opportunity to connect more with their local community in a safe and environmentally sustainable way.

If other suburbs implemented the policies and attitudes of New Brunswick, many more North Americans could choose to live in a smaller city without the worry of a car payment or the fear of a car collision.