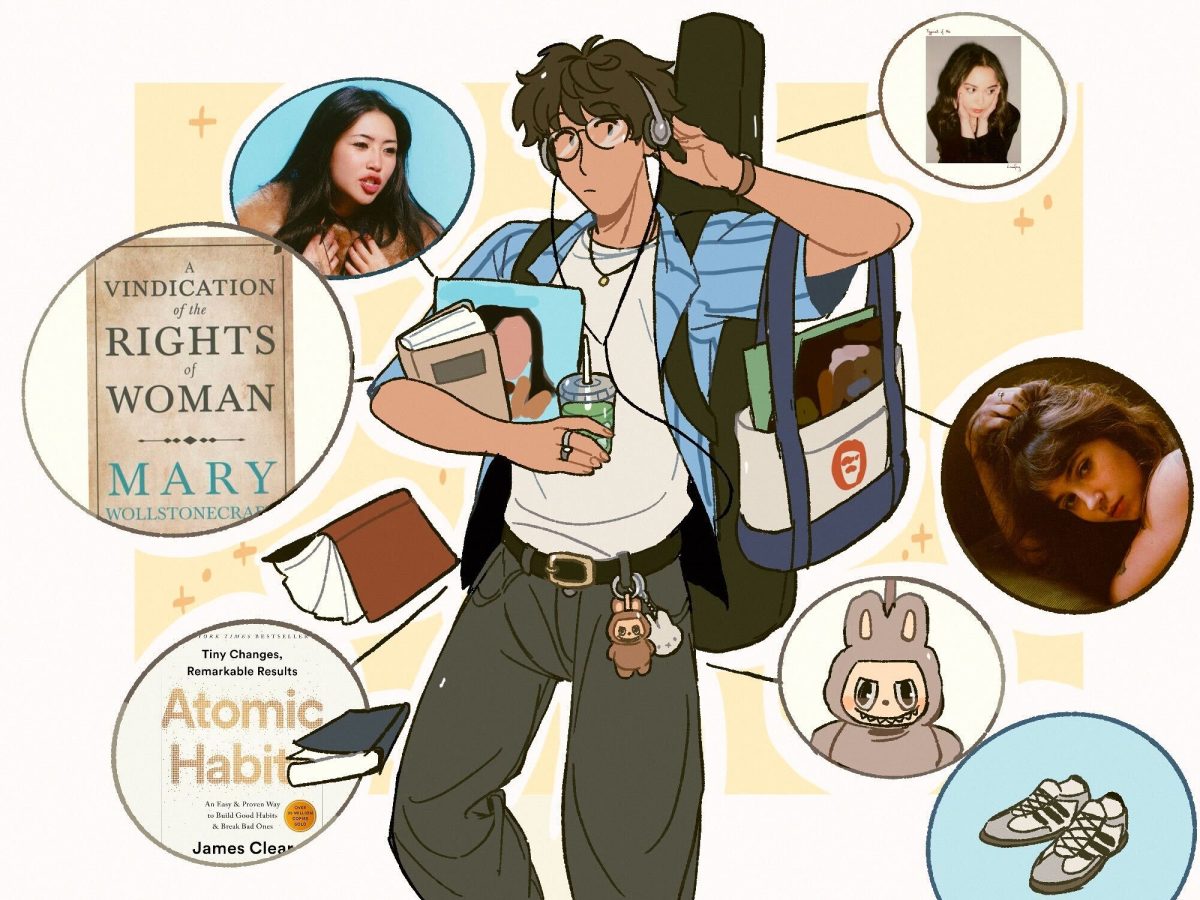

“Influence” may be the defining word of this decade’s culture. From the act of influencing to the new profession itself, social media has made a theoretically intangible phenomenon inescapably tangible — that is, overwhelmingly materialistic.

If a product goes viral on Tiktok, chances are it’ll sell out. We’re so easily influenced by the veneer of authenticity that the algorithmic randomness of TikTok perpetuates.

It honestly feels like satire. I can’t go anywhere without seeing a Stanley Tumbler, nor can I enter any Barnes and Noble without seeing Colleen Hoover’s books plastered on every stand, all thanks to TikTok’s ability to impact the masses.

This isn’t to give off the impression that I’m immune to being influenced. I’m the first to admit I conform to countless influencer-endorsed trends.

But now, influencing is giving way to de-influencing. Instead of advertising what to buy, it’s all about informing the masses of what not to buy.

De-influencing seems to be based on the presumption that we have a running list of products embedded in our collective psyche. This list, it seems, is impossible to sort through ourselves.

Some argue that this trend is beneficial, pushing consumers to be more cognizant of their spending habits.

While I agree that working against the aggressive appeal of microtrends points in the right direction toward more conscious consumption, it also points in an alternatively bleak direction where we are so deeply entrenched in consumerism that we can’t take ourselves out of it.

De-influencing dangerously sets itself apart from the trends that precede it because its appeal lies in its deception. Namely, it writes itself off as not being what it intrinsically is: a trend.

In an age where everyone is influenced, it’s now cool not to be influenced. De-influencing is not breaking free from the hypnosis of TikTok consumerism.

Instead, it’s a new trend that deepens our reliance on others’ opinions, in turn making us only more vulnerable to the marketing and PR schemes of whatever future trend awaits us.

This is because, at their core, trends are inherently reactionary, especially with the lightning-speed volatility of social-media-borne opinions.

Instead of trends gradually transitioning from one to the other, they often follow a framework of oppositional binaries, referring to two things that define themselves in opposition to the other, like hot and cold.

Trends are marked by this binary of shifting desirability, where what is “in” is defined by what is “out.”

Yet popularity is a balancing act. There’s a threshold of popularity where trends become a self-fulfilling prophecy, a flame that burns quickly and brightly but extinguishes itself in the process.

What is “in” gains popularity until its very popularity makes it “out.”

That’s what’s happening with de-influencing. We’re not suddenly awakening from our materialistic slumber to see the world beyond our obsessive curation of aesthetically enviable lives. We’re not renouncing mindless material accumulation in the name of responsible spending.

Instead, we’re simply reacting to the overpopularity and subsequent undesirability of influencer endorsement.

We’re witnessing the beginning of a new cultural trend that deceptively defines itself against its predecessor while reinforcing our consumerist dependence on influencer testimony.

Let’s pump the brakes before we hail this new era of de-influencing as the ultimate end of mindless consumerism, because, well, it’s merely a new iteration of it.