I worked at a commercial art gallery for an internship last summer.

There were a few things I learned.

One, art is expensive. The cheapest items I can recall were postcard-sized sketches worth around $75.

Two, art is expensive. There was a family that were longtime gallery patrons, and they had a conversation while I was there about which artwork they had previously bought was their favorite. One of them loved one of the pieces in the hallway best. Another chose a painting in the kitchen — no, no, not the sculpture on the counter, the painting.

Three, art is expensive. The gallery owner could break even on overhead costs with one large sale. But that requires one large sale to happen, and those were very rare — even more now than ever before.

Commercial art is only a small subsect of the larger world of the arts, including performers, musicians and museums displaying visual arts. But finding a wide audience for all of it is hard.

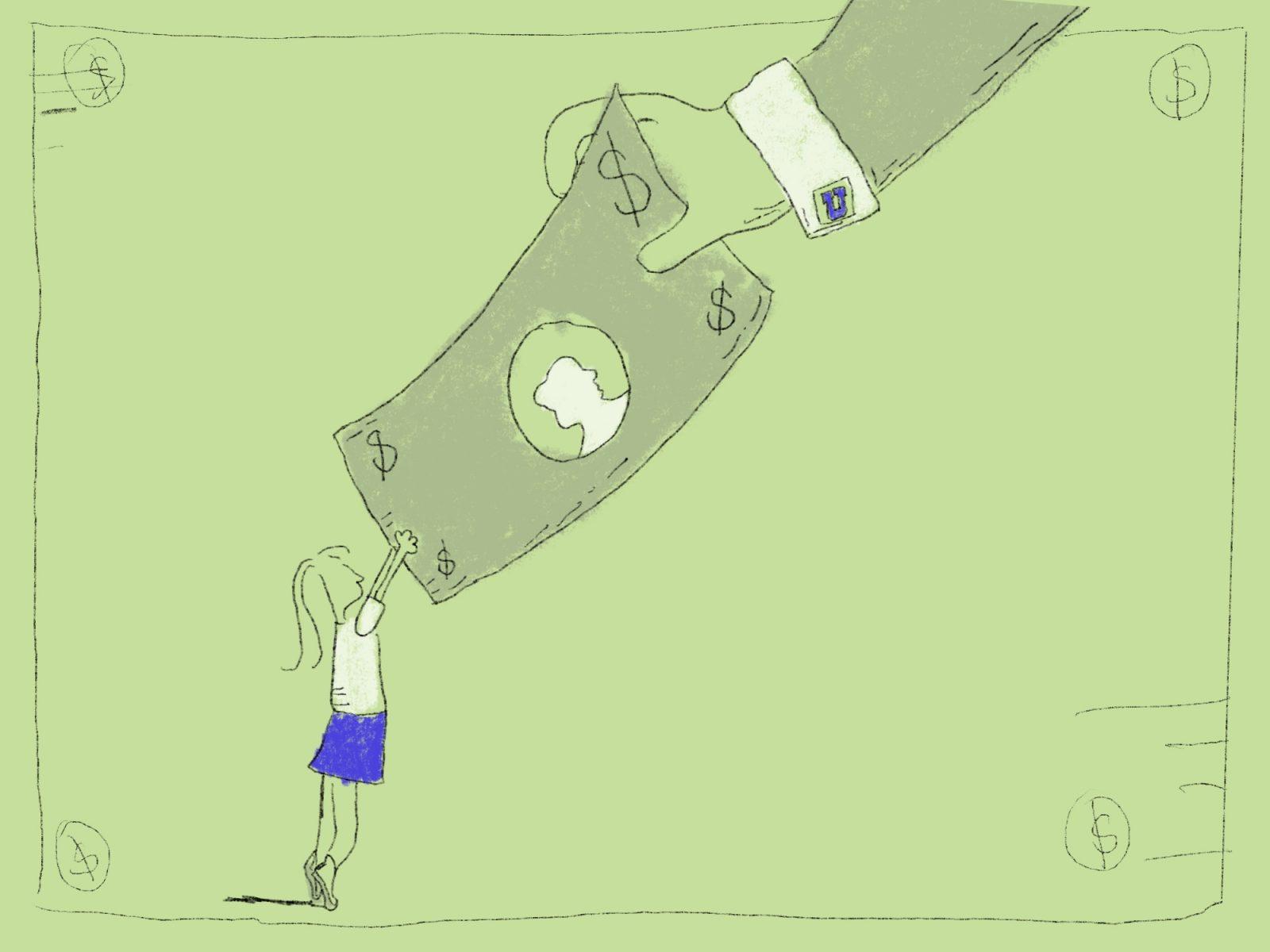

What is happening to the arts is just a continuation of how the world looks at enterprises whose profits can vary significantly, or where the entry level fee exceeds its capability for mass participation. Collecting art is a lot more financially difficult than collecting baseball cards. A pair of a ballet dancer’s pointe shoes can cost over $100 and could wear down in just one day of rehearsal.

That’s why team sports are so popular, for example. Putting a soccer game together is easy enough if there’s a ball, goal, enough space and people willing to play. Putting together an orchestra requires advance planning, cooperation, players, money to pay for instruments and time.

Time is probably the most difficult resource to come by, and everything in the arts is dictated by time. Preparing for a performance of any kind? You’ll need enough time to practice. Throwing pottery, painting a landscape and taking an artistic photograph all take time too. What good is doing something that requires large chunks of time and minimal instant gratification, especially for young children who need engagement and stimuli?

Sports entertainment is not the enemy here, either. Its format just makes for good, digestible content. People worldwide can tune in for their favorite sports — whether it’s basketball and American football in the United States, cricket in India or rugby in England — all from the comfort of their couches. Anything that requires negligible effort and financial investment will inevitably reach more people.

The outcomes of classical music organizations, museums and performing arts are perceived as burdensome to upkeep, and many of these institutions and programs rely on government funding to continue operations, especially in smaller towns and cities where private funding can be scarce.

And in private, commercial enterprise, the cost of art is astronomical. Who knew that a bronze statue sitting in a grand foyer could buy weeks’ worth of groceries?

I do insistently believe that the arts deserve more recognition and provide quality entertainment to a community, as someone who was bad at sports and started dance and music lessons before I started school.

I disagree with anyone who finds classical music boring or argues that dramatic performances like the opera, ballet or theater are for old, rich people. But I can’t fault them for their belief.

The average person is not eating out at “fine dining” establishments all the time, or even any of the time. Why should the average person be expected to invest time and money into the “fine arts?”

The thing that apparently differentiates fine art from the rest is its aesthetic or intellectual value, while other art forms and reasons for creation are more practical in nature. Of course what makes a thing “fine” is its ability to exist for cerebral purposes, because the rich have transcended the practical woes of life to some higher art form.

These designations were made by the wealthy, with the wealthy in mind. But why should we allow the elitists of the 15th or 16th centuries dictate how we feel about art now, fine or not?

Billing art as a “fine” thing isn’t exactly doing it any favors, and just keeps the world of performance and art in antiquity. People can either choose to complain about how no one appreciates a good orchestral performance anymore or bring real appreciation to new listeners and expand audiences past the old, rich or white. Who will take the place of older audiences after they are gone?

I’m not convinced of any solution to the problem. Free access to the arts is a great starting point, but that also requires a government or enough generous patrons to support it. The same goes for the arts in schools, where budget cuts often do damage to performing and visual art departments first.

Above all, making the arts an inclusive, rather than exclusive, industry is the first step. Generating widespread enjoyment is important to survival in this world.

It is unfair that other forms of entertainment make a lot more industrial money, and therefore have more reach than entertainment in the arts. But the movement to bring the arts into mainstream attention will go nowhere if it continues to label itself higher than the people it should be attracting.