Winston Churchill famously grieved that “democracy is the worst form of government, except for all the others.” Indeed, malice and stagnation have marked Washington “democracy” since its inception, but in recent years, the complexity of politics has bored Americans to apathy. In a mess of sequester, chemical weapons and tax law, Americans prefer to leave big decisions to the big men in Washington.

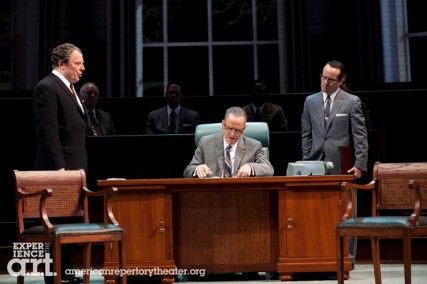

Amidst the haze strikes the lightning bolt that is All The Way, the Robert Schenkkan play that has just begun its run at Cambridge’s Loeb Theatre. All The Way is the meticulously honest — but entertaining — portrait of Lyndon B. Johnson’s first term as U.S. President. Though star Bryan Cranston’s portrayal of LBJ is perhaps the finest performance to grace Boston’s stages in recent years, the true triumph of All The Way is not the entertainment it provides, but rather its invitation for audience participation. While ticketholders found their seats in the Loeb, 1960s leaders slowly took their seats in the Congressional amphitheater onstage, making the thesis of All The Way instantly clear — this play is about all of us.

All The Way begins with the final heartbeats of JFK in November of 1963, which only puts a new rhythm into the step of Lyndon B. Johnson, a career Congressman who longed for his turn in the big office. A self-professed sycophant who sweet-talked his way through Washington, D.C.’s hierarchy, LBJ revels like a schoolboy in his first peaceful moments at the top. Soon, however, the likes of Martin Luther King, Jr., J. Edgar Hoover and Barry Goldwater enter the scene, complicating what was supposed to be Camelot. As the Civil Rights Act, Freedom Summer, his election campaign and whispers of Tonkin torpedoes emerge, LBJ must weigh power over platform and force over friendship.

The strength of All The Way comes in its answer to the complexity of 1960s: simplicity. Dressed only by minimalist Congressional benches, the Loeb stage draws its drama entirely from performance and writing. The ensemble and script — both of paramount caliber — bewitch audiences, even with talk of House Rules and filibustering.

The strongest testament to Cranston’s portrayal of Johnson is that viewers forget that it is indeed Cranston onstage. While arguably one of television’s most iconic actors, Cranston fades into the towering specter of LBJ, adopting not only his southern twang but also his Shakespearean kingly ego, which was insatiably in pursuit of power and legacy.

Animation energizes every inch of Cranston’s LBJ portrayal. Charisma drenches Johnson’s drawl while subjecting politicians to the “The Treatment,” Johnson’s infamous barrage of verbal manipulation to weaken other politicians. Boyish glee effervesces from Cranston in LBJ’s moments of exuberance, like literally jumping on a bed, for example, over simply being president. This dynamism from Cranston underscores Johnson’s moral trajectory after taking the presidency, from sublimating morals for votes to sacrificing friendships for the love — or votes — of faceless Americans. In particular, the everyman touch that Cranston has always possessed allows the audience to understand the scared man behind the presidency. When succumbing to screams at Lady Bird and resorting to tears in boxer shorts in front of political aides, Cranston reveals that before bills and bunting, LBJ was only a man.

Despite the supremacy that Cranston brings to the stage as LBJ, the supporting cast of All The Way shines too. Brandon J. Dirden captures the essence of the iconic Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in both Southern Baptist cadence and confident movements across the stage. Yet, despite King’s seemingly indestructible faith, Dirden does reveal his inner delicacy, a side not often seen and a vulnerability brilliantly exposed on the verge of tears. The ever-present humor of Michael McKean lends great irony and charm to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and actor Dakin Matthews also gleams as the drawling Senator Richard Russell.

Yet, the vivacity of the All The Way ensemble is only possible with the dazzling storytelling of playwright Robert Schenkkan. He skillfully uses parallel action not only to simplify the complexities of the era, but also to illuminate the similarities between Johnson, King and Hoover. This parallel drama allows audiences to marvel at Johnson’s arbitrage as he swindles multiple parties all onstage at once — and to sympathize when those same powers corner Johnson, even when he rages like a spoiled child in response.

All The Way is a triumph because of its great humor and heart. It personifies politics to an attainability that “House of Cards” and contemporaries can only aspire. And, in a time when so many Americans discard their sacred obligation to participate in democracy, All The Way is a godsend. With skill and humor, Schenkkan, Cranston and the ensemble remind us that politics is indeed just an assembly of individuals — sometimes corrupt and sometimes faithful — but always just people.

As such, All The Way does its own part to ensure that our government of the people, by the people and for the people shall not perish.