Crystal Williams, associate provost for diversity and inclusion at Boston University, was in awe of her Boston neighborhood’s great physical demonstrations in support of racial equity. West Roxbury, she said, was demanding change in a visual and tangible way.

But, speaking at Boston University’s discussion series on race Wednesday, she was quick to contextualize how civil rights revolutions such as the Black Lives Matter movement can discount smaller, more intimate moments of racism and discrimination.

Americans tend to enjoy “big, dramatic, symbolic” gestures, she said during the event’s Opening Remarks. It’s what they’re used to, and sometimes these do generate real progress.

“But the results of racist systems and structures and cultures, the chronic stressors Black people and peoples of color feel in this country,” Williams said, “are not often experienced to be big dramatic moments, but rather in the approach to the traffic rotary in our daily interactions.”

Stories like Williams’s, which chronicle Black life — highlighting not just outward racism, but also subtler microaggressions — and demand comprehensive education encompassing Black history and perspectives, built the framework for BU’s “Day of Collective Engagement: Racism and Antiracism, Our Realities and Our Roles.”

The day consisted of 80 speakers across 12 panels who shared expertise on topics ranging from health care to law to student life in the context of racism.

President Robert Brown announced the day in a June 16 email as a way for the BU community to “examine, learn, and reflect” on sources of systemic racism and its effects on campus life. Brown’s message referred to “the heinous murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd” as motivation to learn and understand race with students and faculty.

Brown himself introduced the program, along with Williams and University Provost Jean Morrison. All University operations, including summer classes, scheduled for Wednesday were halted to encourage all within the BU community to participate.

College of Fine Arts professor Andre de Quadros, an advocate for prison reform and education, spoke on a panel concerning criminal justice. He said in an interview he believes addressing ignorance is one important step, although not sufficient to fully resolve racial issues.

“There’s a lot that people don’t know and are not aware of,” de Quadros said. “But knowledge is simply not enough, the world will not change with knowledge, because I think we get desensitized to that.”

Several of the day’s discussions emphasized this privilege and encouraged a reckoning with the past. The Opening Plenary, for example, hosted a conversation around the historic role of racism in the U.S.

Speaker Saida Grundy, an assistant professor of sociology and African American studies, said defining racism begins with understanding the invention of race as a labeling system. Understanding, she said, can become the first step to addressing necessary structural changes.

“Race, as a classification system, historically followed racism,” Grundy said during the plenary. “Colonialism necessitated a false system of human categorization to justify European colonialism. We did not have an idea of race as a category of difference before we necessitated human exploitation.”

While other speakers agreed that this definition is not static, they reiterated that the history and plight of Black people is finite and often absent from syllabi.

Louis Chude-Sokei, director of BU’s African American Studies Program, spoke about the struggle to include POC perspectives when discussing America’s history. Americans are “taught forgetting,” according to Chude-Sokei, who also said the phenomenon is “built into” capitalism.

“This country is really gifted at forgetting,” Chude-Sokei said in the discussion. “[Black scholars are] curators of national and racial memory, or curators of memory that insist that race is a part of it.”

While 13.4 percent of Americans identify as Black according to the U.S. Census Bureau, less than half that is true of BU’s population.

These disparities have affected and continue to affect the BU experience among many POC, as was shared in the intergenerational alumni “Black BU” conversation. Among panelists were 2020 College of Communication graduate Ina Joseph and Joel Gill, who received his graduate degree from CFA in 2004.

Joseph said in an interview her experience at BU was a generally positive one, but that diverse voices within the Black student population alone provides a broad range of different realities.

“I don’t think any student of color’s experience at BU is monolithic by any means, even within the Black community [which] is pretty tight-knit, pretty insular,” Joseph said. “As a non-Black person in this moment, you never want to take space or take attention away from the community that’s actually being impacted the most… but this is going to be a constant learning experience.”

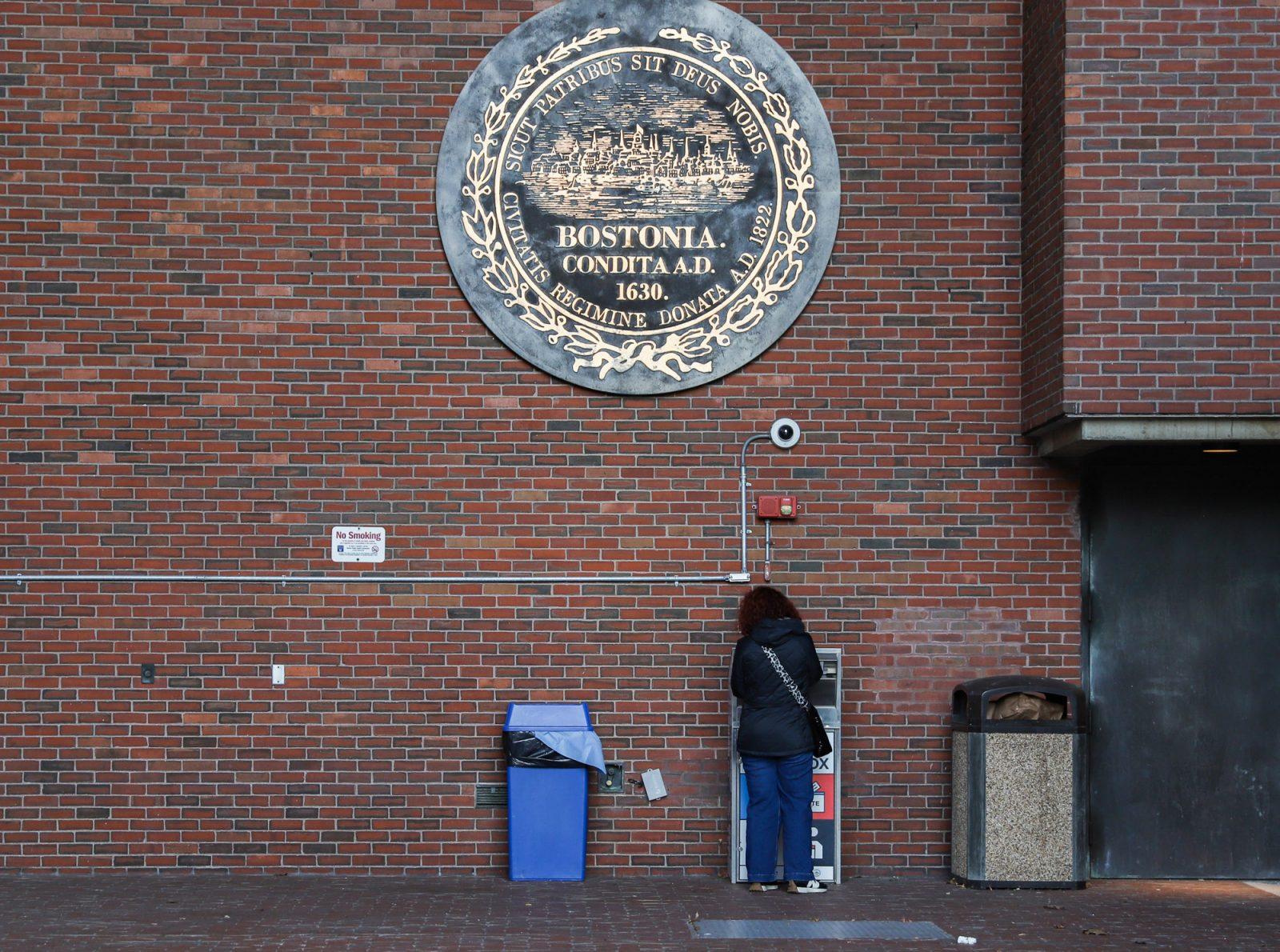

Contrary to Joseph’s on-campus life, Gill encountered warnings of racist behavior throughout Boston. Upon his arrival to campus in the early 2000s, classmates advised him to avoid certain neighborhoods of the city characterized as dangerous for Black people.

This was interesting, Gill said, as it was not something he was used to in his hometown in Virginia. He said that while residing in the South, there was not any specific neighborhood he was afraid to venture into.

“Malcolm X said, ‘At least in the South they’ll tell you they don’t want to sit beside you,’” Gill said in an interview. “That was sort of my awakening, living in a place that was supposed to be the bastion of liberalism.”

Varied Black experiences on campus are now being captured by the new Instagram account, @blackatbu, which posts stories of harassment, implicit biases and harmful racist behaviors committed against students and staff. In its first two days, the account has shared more than 40 anecdotes.

Minority voices spoke throughout the day on numerous collegiate fields of study and the far-reaching effects that racist or white-centric curriculums can have.

School of Law Dean Angela Onwuachi-Willig highlighted the legal and consequently educational ramifications of white indoctrination within the law and the teaching of the law’s practitioners. In a panel entitled, “Racial Violence & the Law: A Sordid History,” she spoke about how legislation can contribute to the violence that the nation is seeing right now.

Onwuachi-Willig said in an interview that while these conversations served immense purpose and are relevant to racial divisions today, they should not end here. These issues, she said, must continue to be discussed throughout the upcoming semester and beyond.

“I hope that people are inspired after these conversations to make this a part of their everyday life,” Onwuachi-Willig said, “that it’s not simply that this is a day of collective engagement, but that it’s a lifetime of collective engagement, that people see this as work that they must do for the rest of their lives.”

She also noted the arrival of Ibram X. Kendi, a scholar and professor on racial discrimination who will head the BU Center for Antiracist Research beginning in July.

In addition to Kendi’s funded work, the School of Public Health has taken action against implicit biases in the health care sector with its “SPH Reads” program.

Yvette Cozier, associate professor of epidemiology and assistant dean for diversity and inclusion at BU, shared the schoolwide reading program in the “Inclusive Pedagogy & Decolonizing the Curriculum” panel.

While she aims to “bridge this divide between students and faculty” by initiating conversations with graduate students, Cozier said she hopes professors across the University continue pushing students to challenge their boundaries.

“These are conversations that we’ve needed to have for a very, very, very, very long time,” Cozier said in an interview. “This deep dive on these topics is what is required of us as faculty professionally, and it’s also what the students are requiring of us every day, so we have to lean into this moment fully.”

As many academics pointed out during Wednesday’s sessions, this learning progress has a long way to go.

Shelly DeBiasse, a clinical associate professor of nutrition and moderator of the “Racism & Antiracism in the Clinical Medical Practice” panel, wrote in an email that Black women are more likely to have pregnancy complications than white women.

“We scientists often use [race or ethnicity] as a predictor variable when we conduct outcomes research,” DeBiasse wrote. “What we need to understand is that it is not race/ethnicity itself that influences health care outcomes, but rather racism.”

Derry Wijaya, assistant professor of computer science, said even facial recognition software harbors racial biases for non-white participants.

Wijaya, who presented her work in the “Research on Tap” panel, said the artificial intelligence community faces ethical dilemmas. Lack of diversity in the computer science field, she added, could contribute to these analytical problems.

“We have to get better, I think, in terms of recognizing bias in the data or trying to make algorithms that are less biased,” Wijaya said in an interview. “[We need] more people from diverse backgrounds to be able to have diverse perspectives that can spot problems.”

Despite the many lags in racial diversity, Morrison said during closing discussions that the University is committed to hiring more Black and Latinx faculty. However, due to slow staff turnover each year, she said increases in diversity won’t be immediate.

“There are a variety of different things that we are doing,” Morrison said, “and there are a number of different things that we need to do as well.”

Carrie Preston, a professor of English and Women’s, Gender and Sexuality Studies, moderated a discussion on white allyship. She said in an interview that the day most importantly addressed the flaws and mistruths that pervade almost every facet of societal life, and that no one can be a perfect advocate for change.

“One of the things that I’ve certainly learned in my own journey towards allyship is that I don’t have the answers, and some of my best intentions, in fact, aren’t what is most needed or most important at any given moment in time,” Preston said. “I have to be prepared to learn and make adjustments, and then unlearn all the horrible things I learned growing up in white supremacy. I think we were all raised in the wrong way.”

Allison Pirog and Madeline Humphrey contributed to the reporting of this article.