Joy Harjo, a member of the Muscogee Nation, is the first Native American poet laureate of the United States. The poet spoke to the Boston University School of Theology Sunday about the intersections of poetry, spirituality and social justice.

The Zoom presentation was STH’s Lowell Lecture for this Fall as part of the University’s Alumni Weekend.

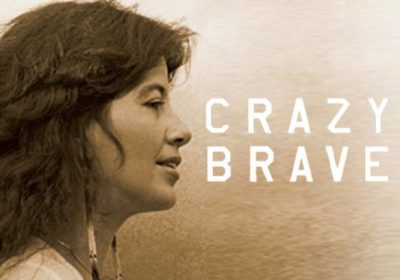

At the event, Harjo recited poetry and passages from her 2013 memoir “Crazy Brave,” and discussed the impact and authenticity poetry holds.

“We can go to poetry to speak about and listen to the deepest truths of what’s really going on in our world,” Harjo said. “We’re the storytellers, we hold the stories of Earth.”

Harjo said during the discussion all words have power, and that it’s important to use them as a means of connecting with the environment. Her definition of spirituality encompassed a connection with the natural world at large.

“We are in a spiritual system that crosses many thresholds, many realms of perception and knowledge,” Harjo said. “It’s not this land is your land, this land is my land, it’s we are the earth.”

Harjo, who edited the Native poetry anthology “When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through,” shared stories specific to her culture and upbringing. She spoke about her mother’s death: she had wanted to wash her body before it was taken for burial, but ultimately could not.

This experience, she said, spurred her to turn to poetry as a way of channeling overwhelming emotions into something powerful.

“The poems, they can hold greatness, they hold our fears, they can hold what we can no longer hold,” Harjo said. “One thing I’ve learned is that if we don’t resolve something, it can be carried on by our children or grandchildren.”

One student who attended the event was Malkah Pinals, a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences. She said she enjoyed hearing the poems Harjo shared.

“I appreciate how Joy emphasized the power of poetry, and specifically when she mentioned how it can hold what she couldn’t express or do in person in terms of caring for her mother,” Pinals said. “The poetry carried what she wanted to say and do.”

The poet laureate also spoke about the importance of ancestral relationships, opening the presentation by discussing her strong relationship with her great grandfather, whom she has never met. Harjo said he has guided her and that she feels his presence often.

Harjo continued her talk by reading passages from her memoir that included her early brushes with organized religion, and the way she was unnerved by the Methodist belief that she would “burn in the fires of hell” if she did not profess her faith before the church.

Harjo also told a story from Vine Deloria Jr. about a Lakota man who enjoyed attending different types of church services — each denomination was trying to “win him over,” but his religiosity manifested as appreciating different conceptions of God rather than dedicating himself to one denomination.

Hazel Monae, a 2019 STH graduate, is the manager of leadership development at Boston’s Episcopal City Mission. On Sunday, Monae introduced Harjo and acknowledged the impact of Harjo’s memoir as well as the “stolen and unceded land” the poet grew up on.

“This particular book really changed my outlook on life and it gave me some words, imagery and wisdom that allows me to really return home, home being to myself, to creation and to all of the community that surrounds me,” Monae said. “It is important for me to recognize that we benefit from the wealth created from the forced removal of Indigenous peoples across this country.”

In her talk, Harjo also discussed her poem “Red Bird Love,” inspired by her observing a family of cardinals over time, which enabled her to see a young bird come of age. The poem draws heavily on imagery, describing the birds as if they were human.

“This is not personification. I don’t call this personification, I call this real life,” Harjo said. “Humanness is there to be found in all living things.”

In the final moments of her presentation, Harjo said all of written poetry is an examination of the poet’s personal and real-life truth.

“If you feel comfortable or easy [when writing], then you know that you’ve gone off-kilter, because it’s demanding and it will demand the truth,” said Harjo. “It’s important to speak the truth in the wound, otherwise the lies will just dig themselves in.”