The gaming industry has been blown to pixelated bits.

It’s not because of its games. It’s not the expensive, downloadable content or DEI controversies.

It’s how the industry is treating its workers — the very talents who make the games we know and love.

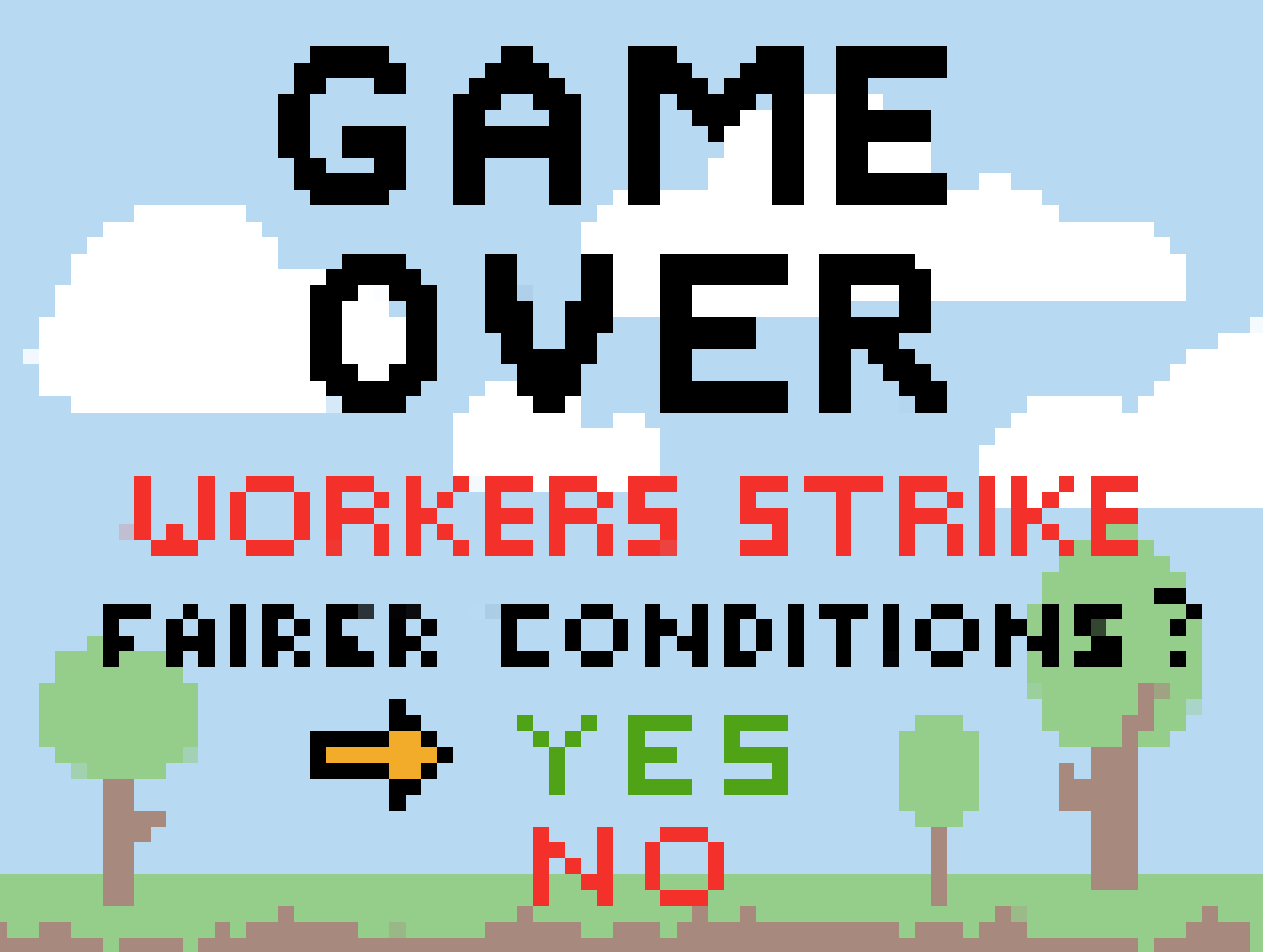

“Le Syndicat des Travailleurs du Jeu Vidéo,” or the STJV, made this issue apparent Feb. 13 in France’s first nationwide video game industry strike.

STJV was created seven years ago, and is now France’s biggest game industry union. It “aims to constitute a friendship, solidarity and defense pact between all workers” of the industry, according to its website.

A blunt assessment made by STJV Dec. 16 said it all: the gaming industry is “a corporate circus.”

So, the union planned for a national strike to transpire on a single day. It was not directed at one company — rather, fingers were pointed at all companies in the gaming industry.

The union made four demands to employers: job protection, transparency, better working conditions and worker participation in decision-making.

More than 1,000 people attended one-day rallies in Paris, Bordeaux and Rennes. Supporters who joined the walkout hoisted colorful flags with “STJV” printed on the center.

On Feb. 12, the union created a Grève — or “Strike” — Bundle on itch.io, a website where users can host and sell independent video games. If you pay $1.00, you get 33 games, and for $10.00, you receive 57. Within five hours, STJV raised $5,000. By the 24-hour mark, it beat its goal of $25,000.

It has now raised more than $43,000 from more than 2,900 contributors.

The strikes did not end at France’s borders — Ubisoft, a French gaming company, saw workers in its Barcelona, Spain, studio walk out. In 2024, the company had suffered its worst year yet. Games flopped. Revenue declined. With sales down nearly 50%, waves of layoffs and studio closures have only increased.

In its third-quarter 2024-25 sales report, Ubisoft dedicated an entire section to its cost reduction plan. It discontinued one of its first-person shooter games, “XDefiant,” closed four production studios and announced “targeted restructurings” that impacted three studios.

In short: Ubisoft cut costs by slashing ongoing projects and laying off developers.

Aside from Ubisoft, Unity, an American video game company, spent $205 million to eliminate 25% of its workforce in November 2024.

The cuts didn’t stop there.

The team behind Unity Behavior — a visual tool that helps control NPCs, or non-player characters, and objects — met its end Feb. 10, when Shanee Nishry, a former senior software engineer, made a forum post announcing she and other developers would not continue working on the package.

Unity released a package many users found useful — not just for games, but for game development. Now, the team behind Behavior, and the dedication put into it, is gone.

Gaming companies like Unity and Ubisoft are swiping off entire visions before they even take off.

So why are all these layoffs even happening?

Many industry analysts have attributed the trend to the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to a boom in the industry as people stuck at home searched for entertainment and escape. As the world climbed back into normalcy, the demand for gaming stabilized and shrunk.

Though demand may have gone down among consumers, thousands of lives were — and still are — affected.

While companies like Microsoft, Sony Interactive Entertainment and Sega America continue to give in to layoffs, Nintendo keeps hiring designers and developers. Not only that, its turnover rate for new employees is close to zero.

This couldn’t be because of its promising work conditions, employee benefits and stellar reputation, could it?

One former Nintendo art director and producer, Takaya Imamura, worked at the company for 32 years.

“There is no company motto. Make the best effort and leave the rest to chance. Respect the spirit of originality,” he wrote in Japanese in a post on X. “The fact that these things are instilled in the employees creates a comfortable environment.”

Of course, being a massively successful company for 135 years helps quite a bit. Still — it makes you wonder why other big companies are choosing not to take care of their employees.

To combat poor working conditions, STJV has suggested a plan to sustainably improve the gaming industry: inform workers about the problems within their own industry, raise awareness among public agencies, reorganize game production and create and secure new rights for workers.

“Video game workers, like all workers, must be able to work in dignified conditions,” the union wrote on its website. “To get the recognition they deserve, so they don’t waste their lives fighting to receive what they are due.”

Once, I would have killed to be a narrative designer in the industry, overseeing extraordinary storylines driven by striking playable characters.

But now? No one even wants an “in” anymore — many developers are actually trying to break out.

By extracting the heart and soul of their companies — the workers — employers are the ones losing in the end.

When companies like Ubisoft cut costs by cutting jobs, they end up with surface-level games, hollow husks of what could have been. They lose money and the faith of their consumers.

Unless real changes are made — this cycle will only continue.