A growing skills gap in the United States has caused a struggle for employers to find qualified workers to fill open positions, according to a Thursday analysis conducted by CareerBuilder and Emsi.

Science, technology, engineering and mathematics fields are critically affected by the gap, the study noted. Even so, other areas such as human resources management, economics and graphic design also show wide vacancies, and the study showed that 63 percent of employers are concerned with the gap growth.

According to a study commissioned by CareerBuilder, of more than 2,300 employers surveyed, 49 percent have been negatively affected due to larger job vacancies. Twenty-five percent reported revenue loss, and 43 percent reported lower levels of productivity.

CareerBuilder spokesperson Ladan Nikravan wrote in an email that programs within the skills gap have grown over the past few years. However, the growth is still not enough to keep up with real-time job demand.

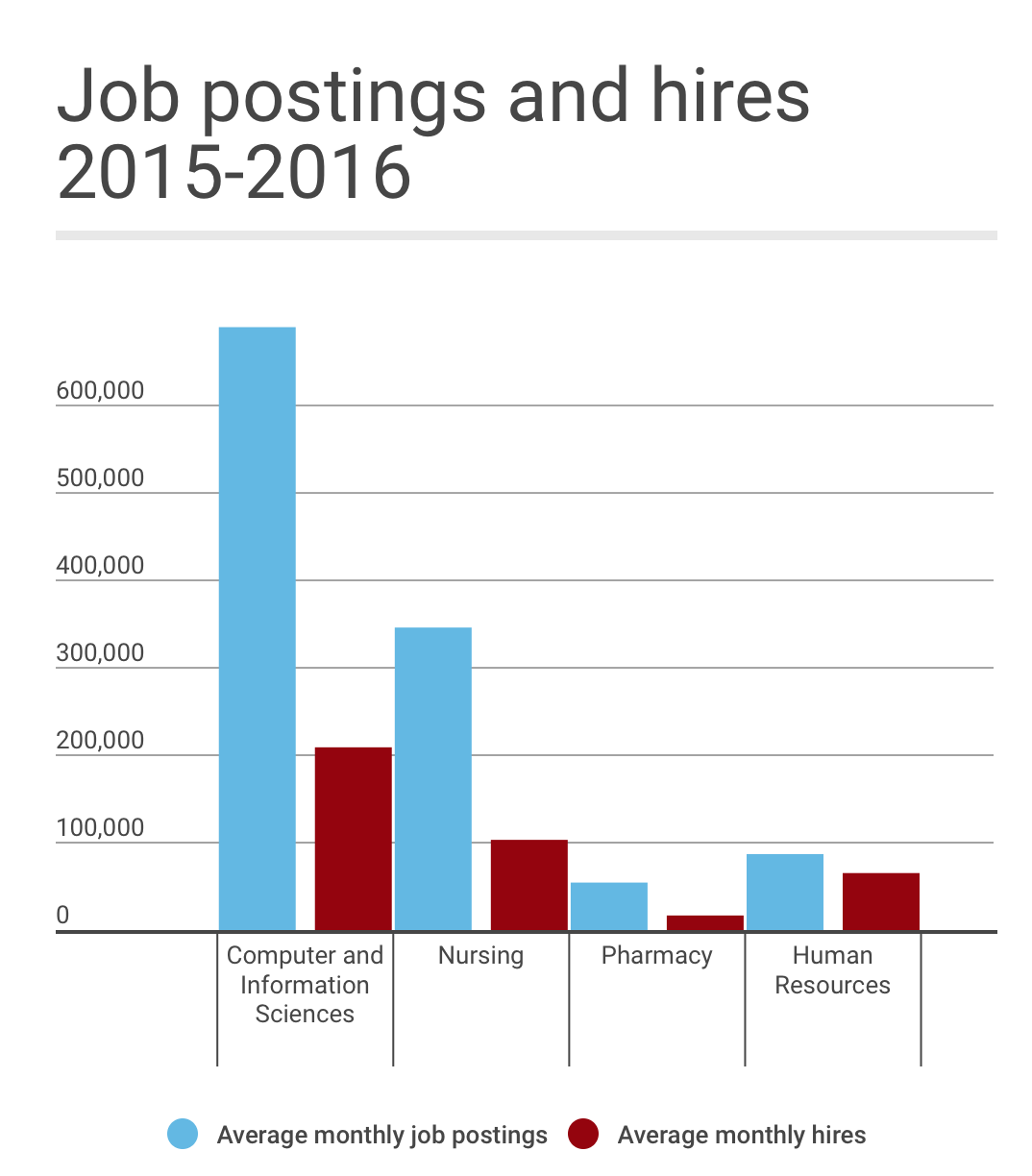

“While the educational programs highlighted in our study have grown at least 10 percent from 2009-2014 and had at least 10,000 completions in 2014, they’re still undersupplying candidates for occupations that already see big gaps between the number of jobs posted and the number of hires companies make each month,” Nikravan wrote.

Communication between employers and academic institutions would be one way to fill the skills gap, Nikravan suggested.

“We’ve been encouraging employers to connect with academic institutions to ensure their educational and degree programs are aligned with the skills employers need in the future, and it works both ways,” she wrote. “Schools should reach out to companies to find out what skills they need.”

Andy Andres, a natural sciences and mathematics professor in Boston University’s College of General Studies, said students should try to get more involved in the fields that present gaps in order to take advantage of the job openings.

“Students open to the hard work of the STEM fields should consider them to get employed,” he said. “If companies are looking for new people to hire and can’t find them, it means companies could be compromising innovation because of their smaller workforce.”

Shulamit Kahn, a professor in the Questrom School of Business, wrote in an email that there were “misleading statistics” in the data analysis.

“You really need to look at unemployment rates and salary increases in different occupations to see what labor markets are really tight,” she wrote. “Also, in a lot of technical jobs, foreigners will flock to the [United States] if a shortage appears.”

While the study could be a good resource, Kahn wrote, it should not be the only source students consult when making a career decision.

“Articles like this do give students a sense of what might be good growth areas in the future,” she wrote. “They are good complements to what you hear from friends. But you need to do lots more research before you can really spot a shortage that will last until you get out of school or a field that’s got a glut right now.”

According to the study, approximately 47 percent of employers believe the skills gap is an information gap, meaning people are not aware of which jobs are available and growing.

Several BU students said employers, employees and higher education institutions play a crucial part in decreasing the growing skills gap.

Angelica Guarino, a sophomore in CGS, said women are not as encouraged as men to pursue a career in the fields that are experiencing the gap, particularly in STEM.

“Awareness towards women could potentially attract more people to fill the skills gap,” she said. “Also, if schools plant the seed early, it might create more interest. If BU expanded its tutoring programs, it could motivate more people who think those fields are too hard.”

William Muller, a freshman in CGS, said professors should engage students with tasks and activities that would prepare them for the job market.

“I just got here about a month ago, but everyone seems really educated, and the professors seem great too, so I would think that translates into students being ready for a career,” he said. “If professors focus on real-world application in classes that would translate into a career, that would be most helpful for students.”

Nigel Rodriguez, a senior in the College of Engineering, suggested actions that BU could take in order to help reduce the skills gap.

“BU could develop a program where companies can work with sophomores and juniors throughout their time at BU,” he said. “Maybe giving them semester projects that would allow them to have a more hands-on experience and allow them to network within these companies.”