On March 15, Sophie Park, a senior in Boston University’s Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies and a staff photographer at The Daily Free Press, started exhibiting coronavirus symptoms. She decided to document her experience through a quarantine photojournal.

A note from Sophie:

Like a lot of people, for the last couple of weeks (more or less) I’ve been cooped up in my apartment. It started off with me simply social distancing, but ended up with me having to self quarantine and then isolate. I am in good health now, but these weeks have been quite a ride.

Being in one room for most of the day lends itself to a lot of things: introspection, for one, as well as noticing my warped reflection in my roommate’s guitar and relapses into Words With Friends binges. As the world has come grinding to a halt, I have been forced to reckon with the fact that I am (we all are) living through an incredibly new, disruptive, and traumatic period.

In spite of the discomfort, and in a way, because of the discomfort, I picked up my camera. I think it’s crucial to document the world right now — to preserve the emotions, fear and gratitude alike. I’ve also seen this as an opportunity to grow as a photographer, and appreciate the little things, like the shifting shadows cast by the blinds in my bedroom or the way the soap bottle reflects off the sink in the bathroom.

The longer I’ve stayed inside, the more I’ve become obsessed with the windows around my apartment, and all the ways they act like portals into the big world we live in — as scary as it might be right now. Making photos with the most mundane material has kept me sane.

I’ve also been feeling lots of emotions. I didn’t anticipate my senior spring to look this way. I fear for my loved ones. I’m frustrated with our government and healthcare system. Who knows when I will find a job. But journaling to the beat of my photos has been incredibly therapeutic. These are photos from my quarantine journal. They aren’t the most extraordinary, but they’ve kept me grounded in this otherwise uncertain time.

A couple months ago, one of my roommates’ rooms flooded. At the time, it felt a little catastrophic. Chemically laced water kept gushing out of her heater. Now it seems pretty trivial. Anyway, she left her guitar in my room to keep it safe from the water. Fast forward to last Friday afternoon — I’m sitting cross legged on my bedroom floor, having an existential monologue with myself when I notice my reflection in her guitar. I started taking photos. Here’s one.

My roommate Ali started feeling sick a day or two before I did. I ran out to CVS to stock up on “sick supplies”: Gatorade, ginger ale, Robitussin DM, ramen, chicken soup and an oxygen reader. I didn’t find an oxygen reader, but I did leave with two bags of fruit punch and cool blue Gatorade. No, there wasn’t any toilet paper left there, either.

The next morning, I woke up with a tight chest and short of breath. This wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. Sometimes my anxiety crops up in that way. But then came the feeling like my chest was on fire, and the feeling that someone was squeezing my lungs.

I called BU Student Health Services and was told it was unlikely I had the coronavirus. My chest pain, I was told, might be explained by stress-induced gastritis. Even if I had it, I wouldn’t qualify for testing unless I could prove I had exposure to a positive case.

This made sense to me. I decided I would keep an eye on my symptoms. And alas, the quarantine began. I started a page in my everyday journal for monitoring my symptoms.

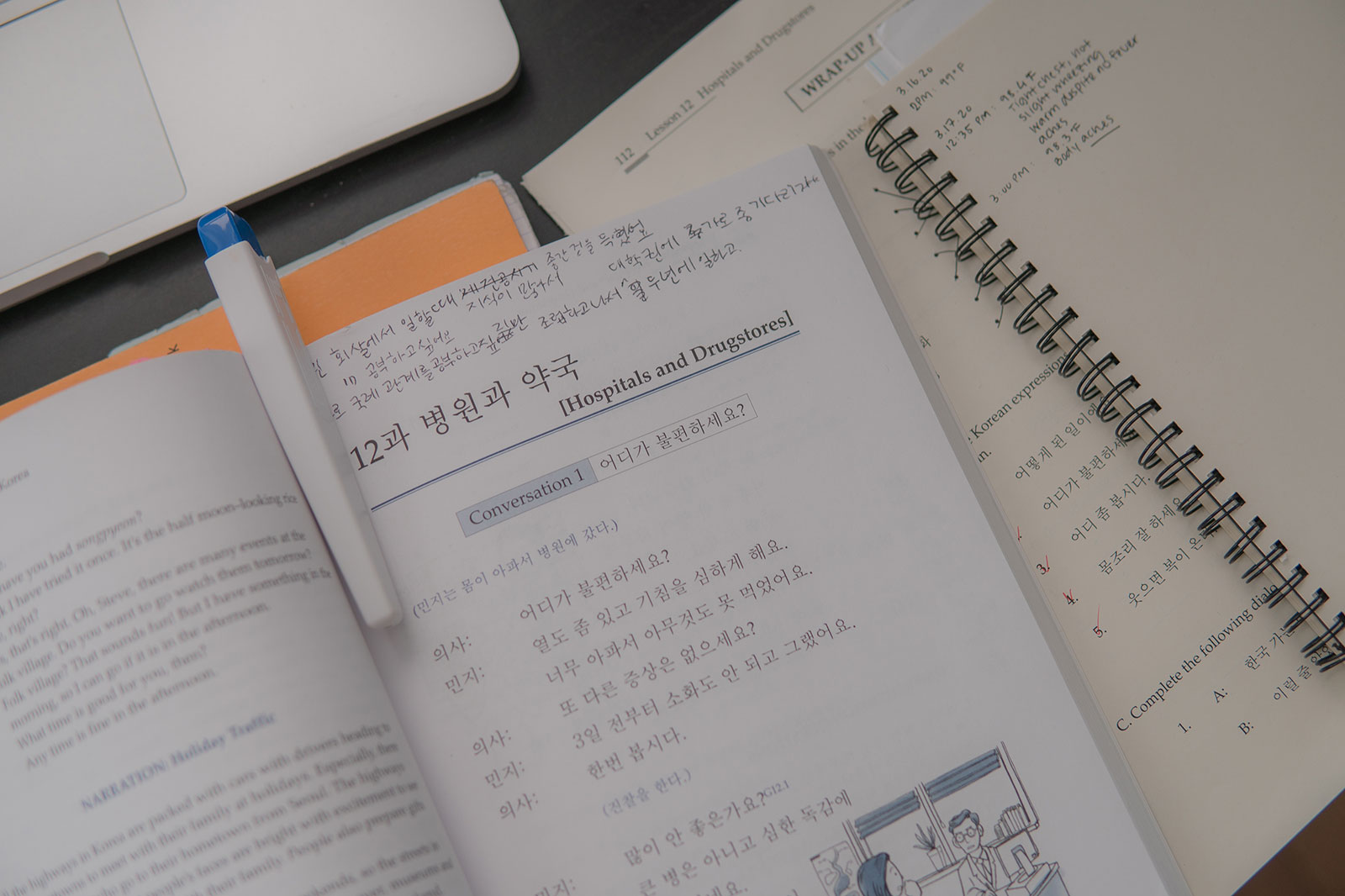

I still showed up to my Zoom classes. Coincidentally, in my Korean class, we were learning about hospitals and doctors. At one point, I looked down and realized I was using my thermometer as a bookmark. How fitting, I thought to myself.

Our apartment was still stocked with Lysol wipes from when we first moved in September. They sat in arms with the rubbing alcohol and hand sanitizer on the counter.

I tried to keep up with the cleaning routine, wiping down the light switches and door knobs, and cleaning the kitchen counter after I ate. But after a while, it felt like I was trying to put a fire out with a tiny pipette.

Wednesday morning, my friend Gabby left enough food on our front stoop to last us 2 weeks.

I wasn’t really expecting the love and care that we received. As isolating as quarantine is, I never really felt truly alone.

Around this time, I started losing my voice intermittently and speaking more softly. It kind of felt like I was running out of usable air — like trying to say a run-on sentence in one breath. I called Student Health Services again. Their system was down.

Small tasks became extremely taxing. Ali and I both had to catch our breath after getting up to go to the bathroom, taking a trip to the kitchen, and even just standing up. My breaths sounded like they were traveling through a flute. Every once in a while, a wheeze would be punctuated by a sharp pain in the lungs. One afternoon, Ali and I were in the kitchen when she keeled over in pain. I happened to be holding my camera.

All the while, I’m thinking to myself, “Is this COVID-19?” The nurse I talked to on Tuesday said it wasn’t. But other medical professionals I had talked to said it could be. I had never had a cold or flu like this before. The symptoms also came in waves — one minute I would be fine, and the next I would feel like someone was squeezing the air out of my lungs. And then I’d be fine again.

Things came to a head on Wednesday night. I had been on Zoom all day, attending three classes and a conference call for a nonprofit I work for. I think my lungs were tired. Around 10 p.m., my body started shaking. Each breath I took was labored. It felt like my lungs were on fire.

For about three minutes, I considered going to the hospital. I’m glad I didn’t go. Ali and I consulted her mom, who’s a nurse. Eventually, my breathing regulated and I went to sleep.

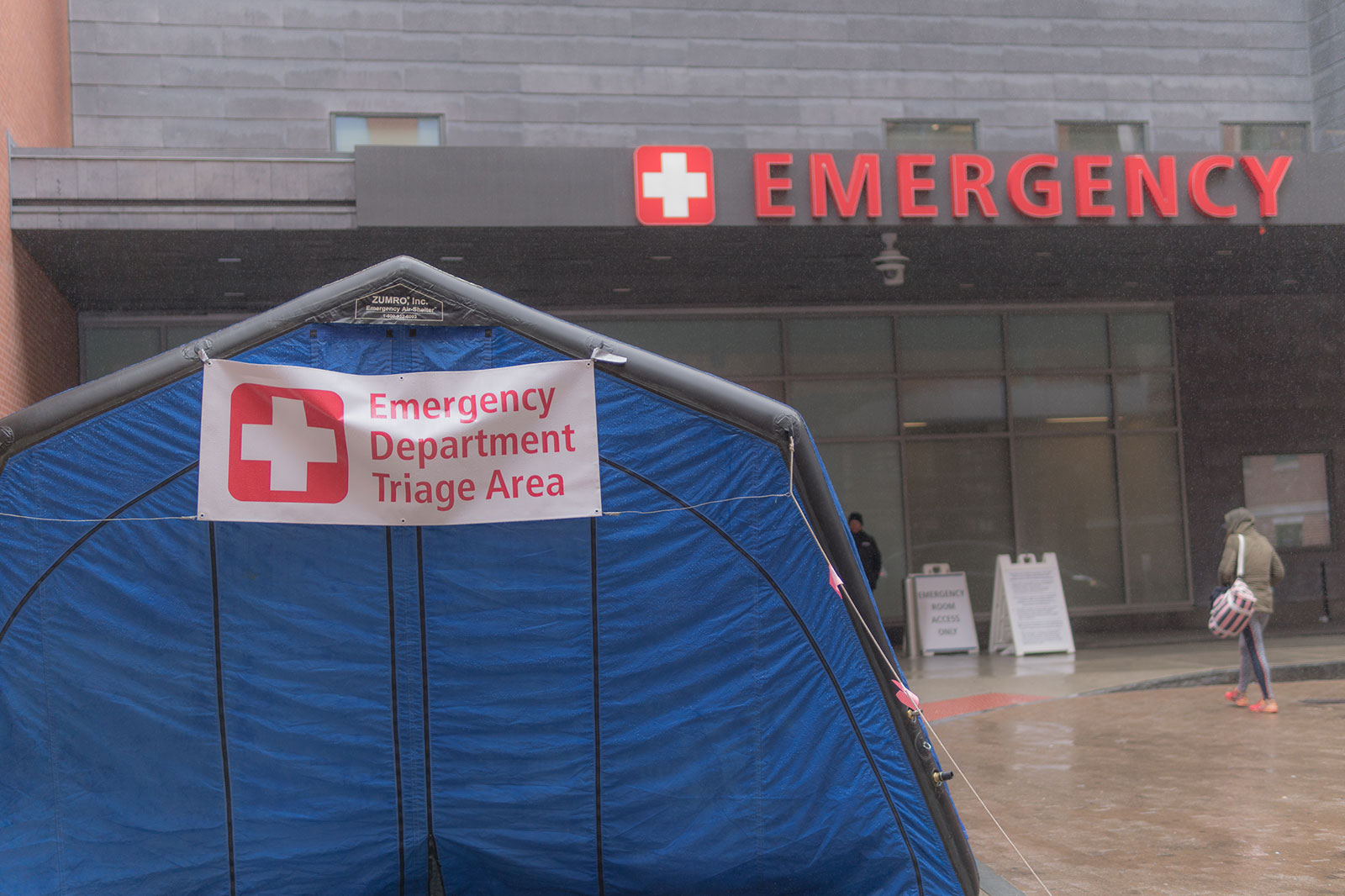

The next day, I called Student Health Services again. The nurse I spoke to said I sounded like a Category 2 case. I’m still not sure what that means. She told me to go to Boston Medical Center to get tested. “Look for a blue tent,” the worker said.

My partner drove me to BMC. I fashioned a makeshift face mask with a tea cloth because I didn’t have a disposable mask at home and all the masks on Amazon were sold out.

We kept the windows down for the entirety of the Massachusetts Turnpike despite the rain.

I found the blue tent and was triaged. A medical worker directed me to a glass building where testing was taking place. Another worker asked me about my symptoms. “Difficulty breathing?” Yes. “Tight chest?” Yes. “Body aches?” Yes. My lungs hurt.

I found the blue tent and was triaged. A medical worker directed me to a glass building where testing was taking place. Another worker asked me about my symptoms. “Difficulty breathing?” Yes. “Tight chest?” Yes. “Body aches?” Yes. My lungs hurt.

I sat down and waited to be seen. The testing area was partitioned off from a lobby area. After having sat in limbo for a couple of days, being at the hospital was reassuring. A doctor took my temperature and clipped an oxygen reader around my index finger. I had no fever and my oxygen saturation was at 100 percent.

I sat down and waited to be seen. The testing area was partitioned off from a lobby area. After having sat in limbo for a couple of days, being at the hospital was reassuring. A doctor took my temperature and clipped an oxygen reader around my index finger. I had no fever and my oxygen saturation was at 100 percent.

“We’re saving our tests for more vulnerable patients,” she said, adding that I couldn’t get tested.

I understood completely. I’m a young, healthy individual with no underlying health conditions. I do have slightly compromised lungs, but otherwise, I’m in pretty good shape. I have a roof over my head and stable finances for the time being.

At the same time, I was pretty defeated. I had spent the better half of the week watching my symptoms worsen, and I had been directed here by someone who thought I needed to be tested. I left BMC with more questions than when I had arrived.

Later that day, I was serendipitously seen at another clinic. I was surprised that they wanted me to come in person. I had previously been told to not physically come in to any ERs or Urgent Care Centers due to fear of contamination.

Later that day, I was serendipitously seen at another clinic. I was surprised that they wanted me to come in person. I had previously been told to not physically come in to any ERs or Urgent Care Centers due to fear of contamination.

I decided to go — my makeshift tea cloth mask now having been replaced by a disposable one I was given at BMC.

After being told I likely didn’t have COVID-19 by one nurse, that I likely did have it and needed to get tested by another, and then being turned away at the hospital, I was feeling a bit of emotional whiplash while also a right-sized bit of hopeful.

Sitting in the waiting room of the clinic, I felt radioactive. When it came time for me to be seen, I noticed that most of the medical staff ducked into other rooms so as not to expose themselves to me.

I was ushered to an exam room, where I was met by a kind doctor dressed head to toe in personal protective equipment. He joked that he looked better this way than without it. I was given three tests: a rapid flu test, a respiratory panel and a COVID-19 test. There’s nothing like having six inches of swab stuck up into your sinuses. I had two nasal swabs, one for the respiratory panel and one for the COVID-19 test. They both triggered an involuntary tear response, but otherwise it wasn’t anything extraordinary. Just pretty uncomfortable.

I had to take an Uber home. As I waited for the driver to arrive in the foyer of the clinic, I thought of the recent onslaught of racist attacks against Asian Americans, and wondered if I would be treated the same. What a time, that something as protective as a medical mask could act like a target instead. My ride home ended up being uneventful. When I asked my driver about working, he said he had gotten too bored at home.

The next week became a waiting game, as well as a continuous mental gymnastics match. I monitored my symptoms more closely. On one hand, I was incredibly grateful for finally being able to get tested. At the same time, I felt a lot of guilt, like I had taken the test from someone who needed it more than I did. For some reason, I was fearful of the test coming back negative, in which case it would feel like I was tested in vain. A close friend reminded me that if there wasn’t a test shortage, I probably wouldn’t feel this way, and that either way, getting tested was the most responsible thing to do. I think she was right.

The next week became a waiting game, as well as a continuous mental gymnastics match. I monitored my symptoms more closely. On one hand, I was incredibly grateful for finally being able to get tested. At the same time, I felt a lot of guilt, like I had taken the test from someone who needed it more than I did. For some reason, I was fearful of the test coming back negative, in which case it would feel like I was tested in vain. A close friend reminded me that if there wasn’t a test shortage, I probably wouldn’t feel this way, and that either way, getting tested was the most responsible thing to do. I think she was right.

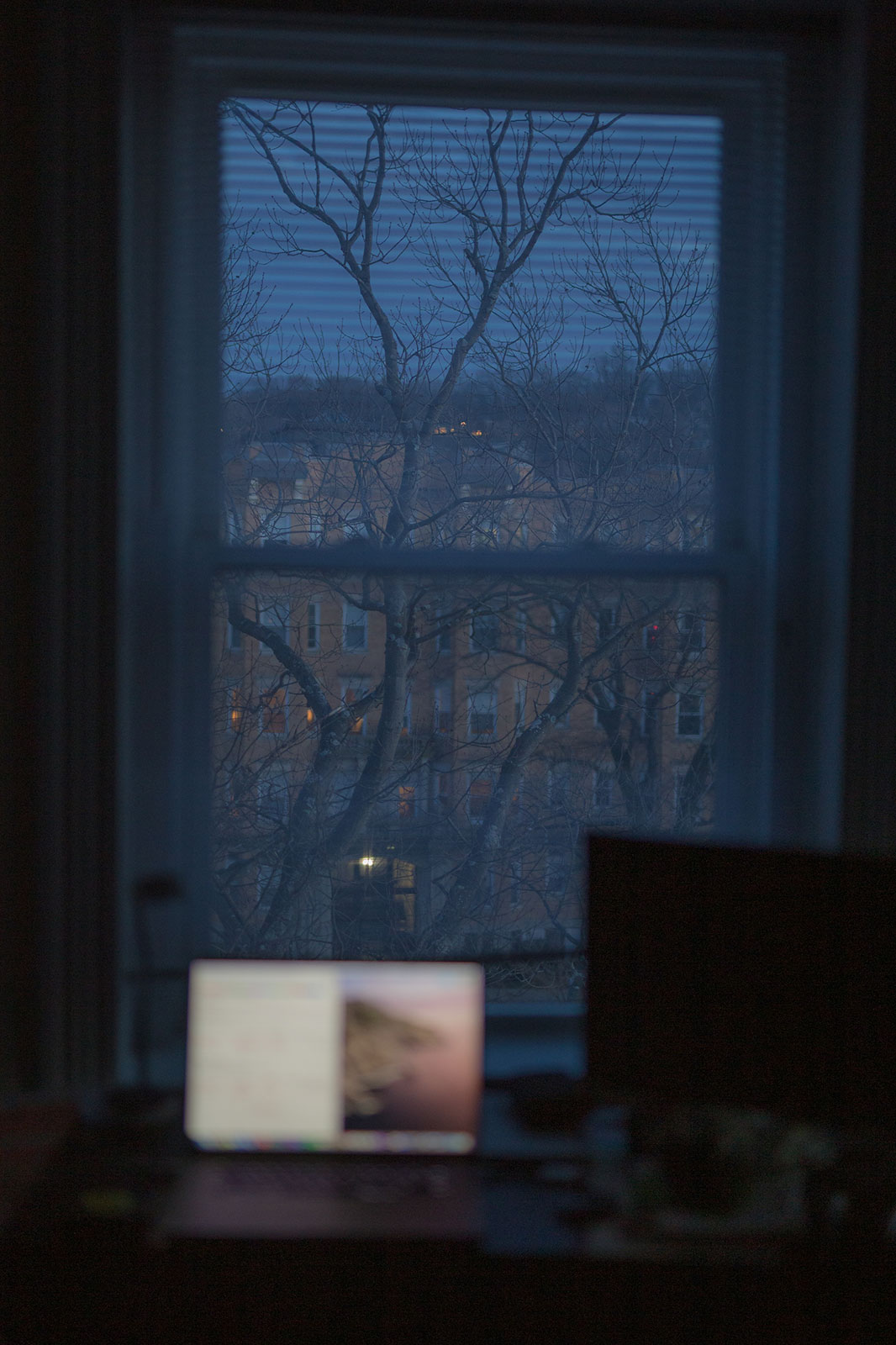

In the meantime, when I wasn’t sleeping or trying to do school work in vain, I became fascinated with all the windows in my apartment. I didn’t have much bandwidth for anything else besides noticing cool shadows and light configurations across the walls.

In the meantime, when I wasn’t sleeping or trying to do school work in vain, I became fascinated with all the windows in my apartment. I didn’t have much bandwidth for anything else besides noticing cool shadows and light configurations across the walls.

With Ali also being sick, we spent most of our days gazing out of our bedroom windows, watching the world go by.

With Ali also being sick, we spent most of our days gazing out of our bedroom windows, watching the world go by.

I was especially drawn to Ali’s window sill.

The scene in my room became a familiar one, too.

The scene in my room became a familiar one, too.

Three days after my tests, I was sitting on Ali’s bed when I got a text from my doctor that my respiratory panel had come back negative. This ruled out different strains of the flu, bacterial infections, non-COVID-19 coronaviruses and other illnesses that would explain my symptoms — a curious development, as I had been weighing the possibility that I had potentially contracted something other than COVID-19. The waiting game continued.

Three days after my tests, I was sitting on Ali’s bed when I got a text from my doctor that my respiratory panel had come back negative. This ruled out different strains of the flu, bacterial infections, non-COVID-19 coronaviruses and other illnesses that would explain my symptoms — a curious development, as I had been weighing the possibility that I had potentially contracted something other than COVID-19. The waiting game continued.

I started taking a liking to the neighborhood pigeons. Their cooing became the musical score to my listless days. I tried to catch frames of them out my bedroom windows when I could.

I started taking a liking to the neighborhood pigeons. Their cooing became the musical score to my listless days. I tried to catch frames of them out my bedroom windows when I could.

Slowly, my symptoms started changing. One afternoon, I was sitting at my desk when the tightness in my chest moved suddenly down to my lower lungs — the wings, as I’ve learned they’re called. Eventually, it passed, and I would intermittently get sharp pains before another round of tightness. I began coughing more. The shortness of breath continued.

The mind games kept on as well. I had been lucky so far. As uncomfortable as my breathing had become, my symptoms were relatively mild. I knew that the test results wouldn’t actually change anything, other than the length of my isolation.

Around the same time, I began seeing reports about false negative tests, with rates of false negatives nearing 30 percent. I wondered if I would fall into that statistic.

The message finally came on Wednesday morning — six days after my testing. I had tested negative for COVID-19.

The message finally came on Wednesday morning — six days after my testing. I had tested negative for COVID-19.

A nurse called me to follow up and I updated her on my symptoms. I felt that I was through the thick of it, but still couldn’t breathe with ease. She cautioned me to act as if I had the coronavirus, because their tests weren’t completely accurate. A few days later, she passed along the Centers for Disease Control guidelines for COVID-19 patients.

Since Wednesday, I’ve connected with a couple of friends who have had nearly identical experiences to mine: COVID symptoms, a test, a negative result and a cautionary word from our doctors about the likelihood of being a false negative ― being left sick and unsure of who or what to trust in a time where everything seems uncertain.

It’s a strange space to be operating in. Since being symptom-free, Ali and I have started taking walks around the neighborhood. If I had COVID-19, then I’m also presumed to be immune to the virus for the time being. But to operate under the assumption that I am still invincible to this illness would be reckless: I’m still exerting caution and practicing social distancing. Eventually, I hope to get a blood test that will confirm whether I have COVID-19 antibodies or not, with the hopes of donating my blood for antibody research. In the meantime, I’m taking life one day at a time.

Greg Marinovich • Apr 9, 2020 at 8:06 pm

Nice response to what life throws at you Sophie!