There’s a reason that the Grammys are second only to the Academy Awards in the pecking order of anticipated awards ceremonies: the Grammys are a show. Despite some tedium from prestigious artists like Metallica and the surviving members of the Beatles, Sunday’s Grammy Awards telecast lived up to its pedigree as the most fun one can have while watching rich people pretend to be civil. Daft Punk consummated their groovy crusade with a performance featuring Pharrell, Nile Rodgers and Stevie Wonder. Kendrick Lamar and Imagine Dragons played an incredibly fun mash-up of “m.A.A.d city” and “Radioactive.” Macklemore & Ryan Lewis offered the peak of ridiculous arena rock spectacle by singing the LGBTQ rights anthem “Same Love” while Queen Latifah presided over the weddings of more than 30 gay and straight couples. Oh, and then Madonna showed up.

Try as they might, however, the fuss over the performances are a pittance compared to the mix of vindication and disappointment that is the response to the award winners each year. The average watcher might only be concerned with what their favorite stars wore or sang, but check any music publication: There are always complaints and concessions and endless qualifications about why this group or that singer didn’t win, et cetera. Every year, fans yearn to simply ask, “Why?”

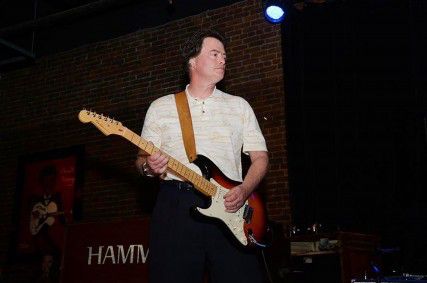

Thanks to Irwin Shur, 55, the Muse has some answers. Shur, who performed professionally for 20 years and runs his own independent label through which he released an album of original songs in 2003, is virtually unknown. This is perhaps the biggest misconception about the National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences, the body that votes for the Grammys: It isn’t an exclusive group of high and mighty artists and producers and record executives. The only requirement for being a member of the Academy, aside from the dues, is a credit on a commercial release.

“It’s not just the music clique,” Shur said. “I don’t know Beyoncé or Justin Bieber.”

As told by Shur, the voting process seems unexpectedly straightforward: Voters are mailed ballots that they fill in with their top choices for each category, and then the winners among those are sent in a second ballot from which the voters mark their choices for the winners. Interestingly enough, voters are only able to vote for 24 of the 78 categories on the second ballot, including the “big four” — Record, Song and Album of the Year, as well as Best New Artist — and then up to 20 additional specific categories.

Shur explained that he exercises restraint where he doesn’t feel he has expertise: “I don’t normally vote for more than about 10, because I don’t feel that I know enough about the other genres.”

While not especially surprising, Shur’s explanation of how he judges submissions and nominees was refreshing in its clarity and impartiality.

“I always think in terms of quality,” he said. “… But a lot of time you also have to think about what the category itself is, because even similar ones like Song of the Year and Performance of the Year are very different things. You might like a song’s writing, but not its performance.”

Shur also explained a kind of anti-sweep method for picking winners, though he might not call it as much.

“You can do some trade-offs in your head in terms of how many awards somebody is nominated for. You can give someone the chance to win in a very close category because there’s another category that they could easily landslide.”

Of all the things Shur revealed, the most likely to draw sighs of relief was his opinions about nominees he’s never heard of.

“Sometimes it can actually work in somebody’s favor,” Shur said. “A good first impression is a convincing thing.”

He had less exciting things to say about his colleagues, however.

“Can someone get sentimental votes?” Shur asked. “Sure. Happens all the time.”

If that wasn’t enough to quiet the cries of upset fans, Shur’s comments on the composition of the Academy make a convincing case for the status quo.

“No one’s ever going to be totally satisfied. Is it a perfect system? No. But there are pros and cons to everything. There are flaws to letting only people or only musicians vote, and of course, if only critics voted, who would choose the critics? I think the fact that the Academy’s membership is not limited purely to the inner circle makes it a little better.”

It’s certainly reassuring to imagine that most of the Academy is made up of people like Irwin Shur, but there’s no way of knowing. Even if we could find out, would people stop arguing about the Grammys? Probably not.