As a core faculty member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University, David Mooney spends a lot of effort on helping humankind, designing devices that reprogram cells in the body in an effort to fight cancer.

Now, Mooney has taken inspiration from his cancer work and has begun working to help not humankind, but its best friend. His idea? A safe vaccination method for chemical pet sterilization to replace surgery.

Mooney recently received a three-year, $700,000 grant to fund the project from the Found Animals Foundation, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that aims to improve the health and welfare for animals. The money comes one-and-a-half years after Mooney’s team originally recognized the need for a humane means of lessening the population of stray animals.

“The main goal is life-long stoppage of reproduction by animals that are vaccinated,” Mooney said. “I’m the owner of two dogs myself, and I can appreciate the decrease in strays.”

The vaccine, according to a Jan. 13 statement released by the Wyss Institute, would target a certain hormone that controls reproduction in male and female animals. Current surgical procedures to sterilize animals — spaying and neutering — are both burdensome and painful for the animals by comparison, Mooney said. That, and they come with a high price tag. The work on the vaccine, though still in the early stages, will hopefully lead to a quicker, more affordable alternative to the traditional surgical process, he said.

“[The animal] would get a single shot with a needle, either in the field or back at the shelter,” he said. “Within a few weeks, it would provide life-long sterilization and prevention of procreation.”

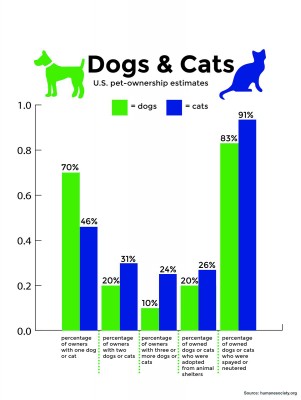

After all, because of the number of dogs without permanent owners, the time needed to administer the vaccine is an important factor in its creation. Across 3,500 animal shelters nationwide, six to eight million animals enter the system each year, with only roughly half finding adoptive homes, according to the Humane Society of the United States. Even then, that doesn’t speak to the countless more strays who never reach the shelter.

“One of the major issues with stray animal health is that they are not routinely seeing veterinarians,” said Lindsay Smith, a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences and the president of Boston University’s Pre-Veterinary and Animal Lovers Society. “Or when someone finds a stray animal, they bring that animal to a shelter where it is often euthanized because shelters have trouble affording healthcare for the animal.”

Smith continued to say that the issue demands attention, even beyond that of “animal lovers.”

“A higher density of stray animals who are not routinely seeing veterinarians is also an area of concern especially in light of disease and animal and human health,” she said. “It’s one that people definitely need to be concerned with too.”

There’s also the economic issue. With a typical sterilization, a stray animal would have to be brought back to a clinic to receive the surgery, followed by post-operation recovery. Shelters already suffer from issues including cramped living quarters and lack of supplies. Running humane surgical operations is often more than the shelter can afford, Smith said.

“The animal could be captured and quickly vaccinated, and then released,” Smith said. “This would also put less stress on veterinarians and shelters that may not have the capacity or the funds to spay, neuter or treat the animal for anything it might need.”

Until then, it’s a matter of making the best of the circumstances. Abigail Erkes, a School of Management sophomore, said she already has a positive outlook on animal shelters.

“The ones [shelters] I’ve been to are very clean and well-kept, and there are people constantly working to make it a nice and happy environment for the animals,” Erkes said.

It’s the most animal lovers can hope for — within reason, anyway.

“I dream of a world where there are cats everywhere, so I think anything to stop that is a problem,” Erkes said. “But then again, all my animals are spayed, so I don’t know the consequences of not having them sterilized.”