Ten months after former Massachusetts Gov. Deval Patrick’s declaration of a public health emergency in March 2014 to combat opiate abuse, the Massachusetts Department of Public Health saw a spike in heroin overdoses and deaths in December.

Scott Zoback, manager of communications at the DPH, said the state’s problem with heroin and other opiate overdoses needs to be addressed to prevent more fatalities.

“Like many states across the country, Massachusetts is facing an epidemic of opioid addiction and overdose deaths,” he said. “We need to address this crisis, which requires taking action in four areas: prevention, intervention, treatment and recovery support.”

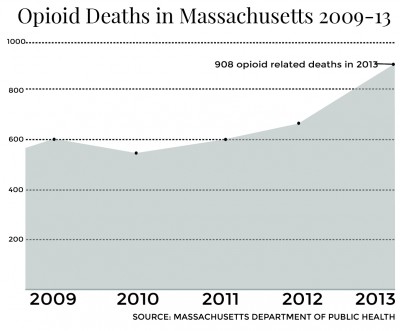

Data gathered by DPH revealed that opioid fatalities have been growing over the past several years. In 2013, there were 908 confirmed opioid-related deaths among Massachusetts residents, up nearly 200 from 2012.

“My guess is that there was something very potent in the heroin,” said Joanne Peterson, founder and executive director of Learn to Cope, an organization that supports families dealing with addiction.

Peterson said the drug was probably mixed with either Fentanyl, an opioid used during surgery, or methamphetamine.

Peterson said December 2014 was one of the worst months she’s ever seen. As of Dec. 18, Massachusetts State Police predicted an additional 115 deaths before the end of the calendar year, bringing the 2014 total, if estimated accurately, to 983 total deaths.

The fundamental issue at hand, Peterson said, is the widespread opiate addiction that leads to heroin use in the first place.

“The opiate is in epidemic proportions right now. And it has been for a long time,” she said. “America consumes 80 percent of all opiate prescriptions in the world. It’s at the point where every person in this country could have a prescription.”

Peterson said the increased usage of medically approved opiates often leads to heroin addiction when the user cannot gain access to a prescription anymore.

To combat this issue, state officials, including U.S. Rep. Joe Kennedy III, are pushing for the reauthorization of a prescription drug monitoring program.

“We can often trace the origins of overdoses across our Commonwealth back to opioid addiction and prescription drug abuse,” Kennedy said in a Jan. 28 press release. “Prescription monitoring programs are an absolutely critical part of trying to come up with a plan to combat this epidemic.”

The program Kennedy is advocating for, National All Schedules Prescription Electronic Reporting, allows doctors to see a patient’s prescription history before they write any prescriptions.

Peterson said she supports the prescription monitoring program and emphasized the need for the kind of care her organization provides.

“The organizations like ours are necessary so that we can provide support, education, hope and resources to families,” she said. “And especially with the Narcan, which is an overdose antagonist — it reverses an overdose. That resource can actually save someone’s life if there is somebody struggling at home.”

Heroin addiction, Peterson said, affects entire families and often communities as well.

On March 7, 2014, U.S. Sen. Ed Markey introduced the Opioid Overdose Reduction Act. The bill outlined findings on opiate use, reiterating that there has been a dramatic increase in overdoses in the past decade. The act also pushed for opioid overdose antidotes and support programs.

The opiate overdose antidote is known as naloxone, or Narcan. In September, the Boston University Police Department began carrying Narcan to help alleviate the growing overdose problem in the city, The Daily Free Press reported.

Domenic Ciraulo, professor of psychiatry at the BU School of Medicine, said Narcan is a significant player in saving the lives of heroin addicts.

“The public health department has promoted Narcan, which really has been a great benefit,” he said. “I’ve seen several patients brought back from death by using the Narcan. It’s usually a matter of supply and low cost that leads to these epidemics, and we see them periodically.”

Ciraulo said support for drug addiction and overdose could use some improvement, especially in long-term recovery.

“We need longer in-patient programs and a more intensive outpatient program available to everybody, especially people who can’t afford to pay it and are being under-treated,” he said. “There is a problem with access and not having enough qualified programs, and once someone is discharged from an in-patient program, there is often inadequate follow-up.”

One program that has proved to be successful is a coaching program that provides a coach to discharged patients to help them stay off the drug, Ciraulo said. Those who don’t have coaches are re-admitted to the hospital more frequently.

Several Boston University students said their personal experiences with the effects of heroin on their loved ones have left a lasting impact.

“One of my best friends in high school — this is why we’re not best friends anymore — she overdosed, and came to my house in the middle of the night, and basically lived there for a day and a half,” said Alli Horowitz, a freshman in the Sargent College of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Horowitz said her friend went from ambitious and focused to self-doubting and lazy once she started using the drug.

“She wanted to be a surgeon,” Horowitz said. “And then once she started using, it was like, ‘Oh, I’m going to community college.’ Her aspirations definitely changed.”

Horowitz said the friend called her from the hospital when she overdosed.

“It was pretty scary. Luckily she didn’t die, because she got to the hospital. Then she went into rehab, and wasn’t allowed to talk to anyone,” she said.

Sally Kim, a freshman in the College of Arts and Sciences, also experienced the distancing and frightening effects of a friend overdosing. She said the experience was psychologically, emotionally and physically draining for both friends and family.

“You hear a lot about people being addicted to substances on TV or in the media or whatever, but until it actually happens to you, I don’t think people understand how draining of an experience it is,” Kim said.

The increase in overdoses in December was not surprising, Kim said, as moods tend to change in the winter months.

“Over the summer, everything is good. I think people are more stable in the beginning parts of the year,” she said. “Later on in the winter, it’s cold. It’s the end of a fiscal year. People tend to get laid off, or something happens to them job-wise. Other things can happen. For a lot of people, it can lead to a relapse into something like heroin.”

Kim said societal pressures and expectations can also lead to addiction or relapse.

“What I’ve found, especially with my friend, is that humans are very prideful. They don’t want to do anything to lessen that or destroy that,” she said. “Especially here in America, there’s the whole ‘American dream. You should be self-reliant.’”

Several residents said the rise in heroin-related deaths is a serious problem in the state that needs to be treated with great care.

Sam DiOrio, 18, of Brighton, said it wasn’t surprising that heroin overdoses were rising, especially because it is such a dangerous drug.

“Heroin is a big deal,” he said. “There are so many negative externalities that are associated with hard drug use, especially heroin. I just feel that it destroys people’s lives.”

Jonathon Maniscalco, 24, of Brighton, said heroin addiction is often the result of other drug use, where the cheapest option is the most hazardous.

“It definitely has its place in the city and fuels people to commit crimes,” he said. “It’s prevalent within the homeless community and paralyzes them because of their situation.”

Travis Nelson, 20, of Allston, said the rising heroin overdoses in Massachusetts are not very surprising, and more support should be offered for addicts.

“Any issue where peoples’ lives are being ruined is an important issue,” he said. “I don’t think we should lock up heroin users. We should help them and help them get rehabilitated.”

Monique Avila contributed to the reporting of this story.