In recent times, there has been a surge of films illustrating the history of a person or event barely a few years in the past. The Social Network gave the history of Facebook even while the site continues to grow today. 2013’s Jobs was released less than two years after the death of Steve Jobs. The Fifth Estate is a film in the same vein. Mostly fictionalized — though based off the real and recent history of WikiLeaks — The Fifth Estate takes an evaluative look at Julian Assange’s whistleblower-founded journalism in a time when Edward Snowden and online privacy are still making headlines.

Directed by Bill Condon, The Fifth Estate tells the story of WikiLeaks and its founder Julian Assange, choosing to go through the viewpoint of Daniel Domscheit-Berg, the organization’s spokesperson and Assange’s hacker sidekick. Much of the information from the film was based off of Domscheit-Berg’s book Inside WikiLeaks: My Time with Julian Assange at the World’s Most Dangerous Website.

Opening with a detailed, beautiful sequence on the origin of the printed word and journalism, the film begins with one of WikiLeaks’s biggest leaks: the controversial publication of the Afghan War Diaries and hundreds of other government cables.

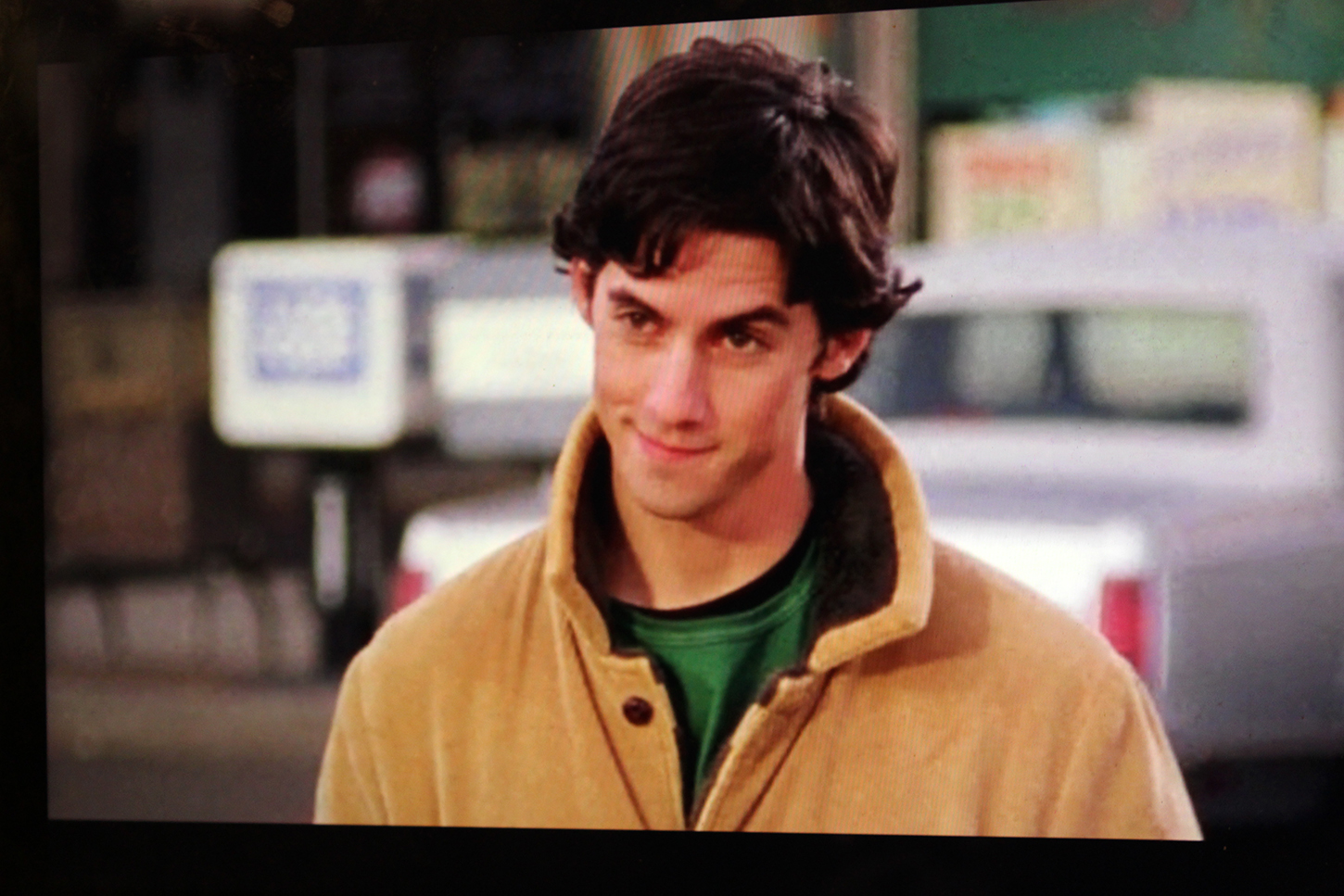

It then proceeds to flash back to 2007 when Domscheit-Berg (played by Daniel Brühl), who goes by Daniel Schmitt when working on WikiLeaks, meets the quirky but charming Assange at a hacker conference in Berlin and first gets recruited to his WikiLeaks project.

Benedict Cumberbatch plays a great Assange: manipulative but charming, accomplished and mysterious, reclusive but passionate. He’s a world-traveled cyber gypsy, bringing justice to people through his insistence on government transparency.

Cumberbatch shows signs of his character’s crazy, sociopathic behavior early on, and skillfully keeps them in check with his righteous world-saving attitude. He masters the expected and unexpected meltdowns, the calm fury and the rogue behavior throughout the rise and inevitable fall of WikiLeaks. Assange turns Domscheit-Berg’s life upside down, but Daniel is up for the ride.

Daniel Brühl also plays his part convincingly well. He’s smart, yet reverts to naïveté when he becomes entranced by the importance of his and Assange’s work. Domscheit-Berg gets sucked into the cause, and both men — as both actors and as characters — feed off of each other’s energy and skills.

Predictably, they get so caught up in the excitement and moral justice of their actions that they take the project too far and begin to question each other’s motives.

For those unfamiliar with the background of WikiLeaks and Assange or confused about the scandal surrounding the website, The Fifth Estate does a thorough job of explaining the process of how WikiLeaks came to be, and manages to do so in a relatively objective and unbiased manner.

Still, this method of storytelling can have its negative consequences. The Fifth Estate begins to lag after the first few scenes, building tension at a sometimes uncomfortably slow pace for half of the film. The concept of WikiLeaks is presented through the surrealistic interpretation of a newsroom that is woven throughout different points of the film. It does not seem to fit the film’s “true story” premise, but nevertheless adds an interesting dimension. What does the exact opposite of this, however, is the sequence of scrolling lines of typed text and tweets that occasionally dash across the screen, which add nothing but a level of cheesiness.

Regardless, the film is definitely enjoyable and, aside from its great acting, it succeeds for one main reason: instead of trying to push a certain side of the argument, the agenda of The Fifth Estate seems to lie in illustrating the complex gray area of legality, morality and justice that circles around the idea and the execution of WikiLeaks.

Throughout the film, Domscheit-Berg and Assange say “editing reflects bias” multiple times, and in this similar fashion, the film presents the story quite objectively. The Fifth Estate shows the multi-faceted issues of trying to balance objectivity with personal privacy, with transparency, with justice, with peace and with journalism’s biggest constraint — time. Perhaps the only truly unexpected part of the film is the very end, after the “story” has ended, where Cumberbatch, as Assange, is mock interviewed.

Humorous and strange, it sill leaves the audience to decide on the merits of WikiLeaks and whether Assange is a saint of justice and truth or just a reckless, selfish crusader waging an “information war” on the world.