In the 21st century, people have countless social media platforms to express their innermost thoughts and feelings to millions of other users. What they don’t have is true anonymity, with one exception — the bathroom stall door.

“There’s this veil of anonymity at play that allows people to express any view, thought or declaration covertly,” said Nicholas Matthews, a visiting communication professor at Ohio State University. “Even if they had a [social media] account that’s not tethered to their name, there’s always this understanding that you could be discovered.”

In 2012, Matthews and his colleagues at Indiana University published “Bathroom Banter: Sex, Love and the Bathroom Wall,” a study of bathroom graffiti in nine local bars in a Midwestern city, through the lens of evolutionary psychology.

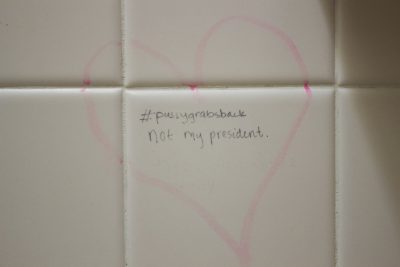

In Boston University’s College of Arts and Sciences, there are 11 public restrooms designated for women. No two are exactly alike, and neither is their graffiti. Etched with everything from thin ballpoint pens to classic black Sharpie, their writings range from political discourse to commentary on boys to supportive messages about self-worth and mental health.

On one stall, a writer left a simple prompt: “What/who/how/where/why do you love?” The responses vary widely, including “weed,” “FOOD,” “Myself, and those whose love me just as much” and “Girls” followed by “F*CK YEAH GAYNESS!!!”

The last pair, in which the responder assumes the first writer identifies as a woman who likes women, highlight what Matthews said researchers have theorized as a uniquely motivating property of bathroom graffiti: the opportunity to speak to one’s gender at large.

“It’s interesting because you have this super diverse group you’re speaking to in a somewhat public place,” Matthews said. “But despite that diversity [the bathroom] cleaves the number of people in half because you’re speaking to, essentially, a single gender.”

Being able to speak anonymously to a large yet somewhat unified audience gives writers a chance to air gender-specific messages or grievances, Matthews said.

On several stalls, female students wrote about their frustrations with boys and platonic break-ups: “Fu*k those damn boys!! We deserve better than some cute dinners and floppy d*cks” and “How to move on from a friendship? treat it like a break-up, communicate w/ them until you have closure. then invest in your other friendships & try not to dwell on it.”

Matthews’ study classified many different types of bathroom graffiti: sexual, romantic, religious, political and even scatological (writing referring to defecation). But there’s one type of graffiti his study didn’t find — messages of support, many of which can be found on the women’s restroom stalls in CAS.

Most often, they’re written in the style of affirmations: “You are loved,” “You are so loved, beautiful, and valued,” “If you feel unloved, I love you.”

According to Matthews, none of the existing research about bathroom graffiti discusses that kind of writing. However, he said he’s been contacted multiple times about positive graffiti left on women’s bathroom stalls around college campuses.

“From the people I’ve spoken to on the phone who have been interested in this subject, most of the time they call me because of interesting on campus, and a lot of it is supportive,” Matthews said. “I don’t really know why it’s specific to college campuses and female authors in particular, but … there is some prevalence to this.”

At its core, Matthews said, graffiti allows us to make the intangible tangible.

“From ancient peoples all the way to us now, we’ve always this tendency to sort of mark territory,” Matthews said. “One of the reasons behind this is to make something that is intangible, like your existence at a given place, to make it real.”

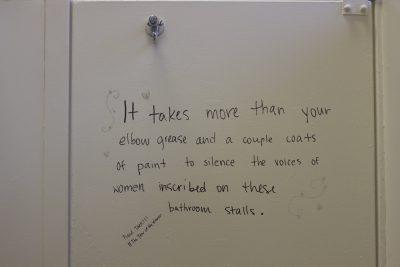

Faced with various causes of decay — time or regular maintenance, for instance — even the boldest markings will eventually become indecipherable. But, as one writer espoused, that won’t ultimately be enough to silence the anonymous voices.

“It takes more than your elbow grease and a couple coats of paint to silence the voices of the women inscribed on these bathroom stalls.”