The creation of new art forms goes hand in hand with new technology, and the moving image — being one of the newest and most expensive art forms — is a privilege that we get to both create and experience.

But many regions across the globe do not have that same privilege, which is why it’s vital to spotlight cinema from countries massively underrepresented in the film industry.

Up until a few years ago, the Saudi Arabian film industry was essentially non-existent. The country had banned movie theaters since the 1980s, and filming in the country was, and still is, an extremely tenuous task.

So for “Wadjda” to be the first feature film shot entirely in the country was a big step in the right direction for the budding filmmakers of the region. What’s even more improbable is that the film was directed by a Saudi Arabian woman — Haifaa Al-Mansour

The conditions under which Al-Mansour created this film are some of the most strenuous of any modern cinematic project, and it’s demonstrated in the five whole years it took to get it from start to finish.

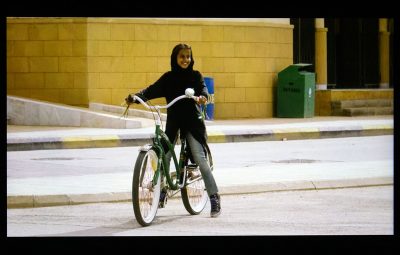

The plot of the film is a relatively simple one. Wadjda, played by Waad Mohammed, is a friendly and adventurous 10-year-old girl. Wadjda and her family live near Riyadh, the country’s capital, and their community is one that heavily values tradition.

One day, Wadjda passes a store selling an eye-catching green bike and she decides that she’s going to do everything in her power to have that bike for herself. However, a couple of things get in the way of that dream.

At 800 riyals, the bike’s cost is an issue for her family, so Wadjda searches for odd jobs she can save up, and also enrolls in a Quran recitation competition. But the greatest obstacle she faces is that a girl riding a bike is deemed unacceptable by her community.

Wadjda meets with many characters, most of them nice people who want to help her, except for Ms. Hussa, the headmistress at her school. Wadjda’s sidekick is Adbullah, a boy of a similar age, who strongly believes that he would be able to beat Wadjda in a bicycle race.

The movie is briskly paced and without much downtime as we’re always following Wadjda around or getting introduced to subplots. Within these stories, Al-Mansour creatively pushes societal issues to the surface.

There is a subplot of Wadjda’s grandmother wanting her son to remarry because Wadjda’s mother cannot have children anymore, and they wanted a son instead of just a daughter. There is a scene about homosexuality between two young women and how the community treats them for it. There’s a scene about deportation and the exploited leverage that legal citizens have over those who are not.

But these topics aren’t fully explored. This isn’t due to a lack of want from Al-Mansour, but instead it was because she had to be gentle in her approach to address these topics, so the film could be approved by the Saudi government.

This is a significant reason why the movie ends on a positive note, though I personally found the last shot to be melancholic and not as happy as the soundtrack would suggest. And while the film’s content was restricted, its creation and existence is what makes it such a landmark movie.

Due to the country’s laws separating men and women, Al-Mansour had to direct the film from inside the walls of a small van. She used walkie-talkies to talk to cast and crew, and saw what they were doing on set from a remote monitor.

Once the movie was completed, it became another challenge to get Saudi residents to watch it. Until 2018, there was a ban on movie theaters in the country, and while some people traveled out of the country to watch it, this was a privilege only those with money to spend could really do.

Luckily, options are starting to become readily available for Saudi Arabians to consume not only Al-Mansour’s film, but other local and global cinema. It is expected the country will have around 350 movie theaters by the end of the decade and 2,500 movie screens.

There are also more films being made, though all extremely recently. “Wadjda” sticks out when looking at a list of the most popular Saudi Arabian movies — it’s the only feature in the top 50 made before 2016.

“Wadjda” is subversively complex despite its straightforward storyline, and the conditions upon which it was made makes it a true cinematic gem, and an inspiration for female filmmakers and creatives across the globe.