Universities are, for many, a first departure from the comforts of home. However, for many, the idea of “home” is very different. Many attendees of private universities across the country call the United States home, proven by a sometimes-arbitrary piece of paper known as proof of citizenship. Yet, many others who attend these universities do not possess such papers. They attend your classes, perhaps even sit next to you, but you may never know. So many others do not have this privilege, graduating from high school yet unable to enroll in an institution of higher education because of an immigration status. The inevitable question arises — How should universities react?

Harvard University students rallied Monday afternoon to advocate for a “sanctuary” of sorts on campus, particularly in these tumultuous times, according to a Boston Globe article. A Boston College student group also hosted an event on Monday afternoon, which over 300 people attended. Both rallies arose in response to President-elect Donald Trump’s wavering statements on immigration, which have swayed from grave and frightening to perhaps less so in the last few days. Despite the gravity of the situation, students whose statuses in this nation are not concrete rely on universities for answers in this time.

In the Globe article, undocumented Harvard student Bruno Villegas expressed his thanks for attending the university he now calls home

“Being [at Harvard] has been one of the best experiences of my life,” Villegas said. “Things are uncertain, but there is so much hope and there is so much love.”

Though Harvard expressed their “support” of enrolled undocumented students, the lengths to which that support extends was not truly called into question until now.

Universities are, at their core, hallowed hallways of learning. A degree from a university opens doors in this nation and elsewhere, and graduating from an American university in particular is something that can never be stripped from one’s identity. The knowledge and skills learned in those classrooms stratify segments of the population, whether we like it or not.

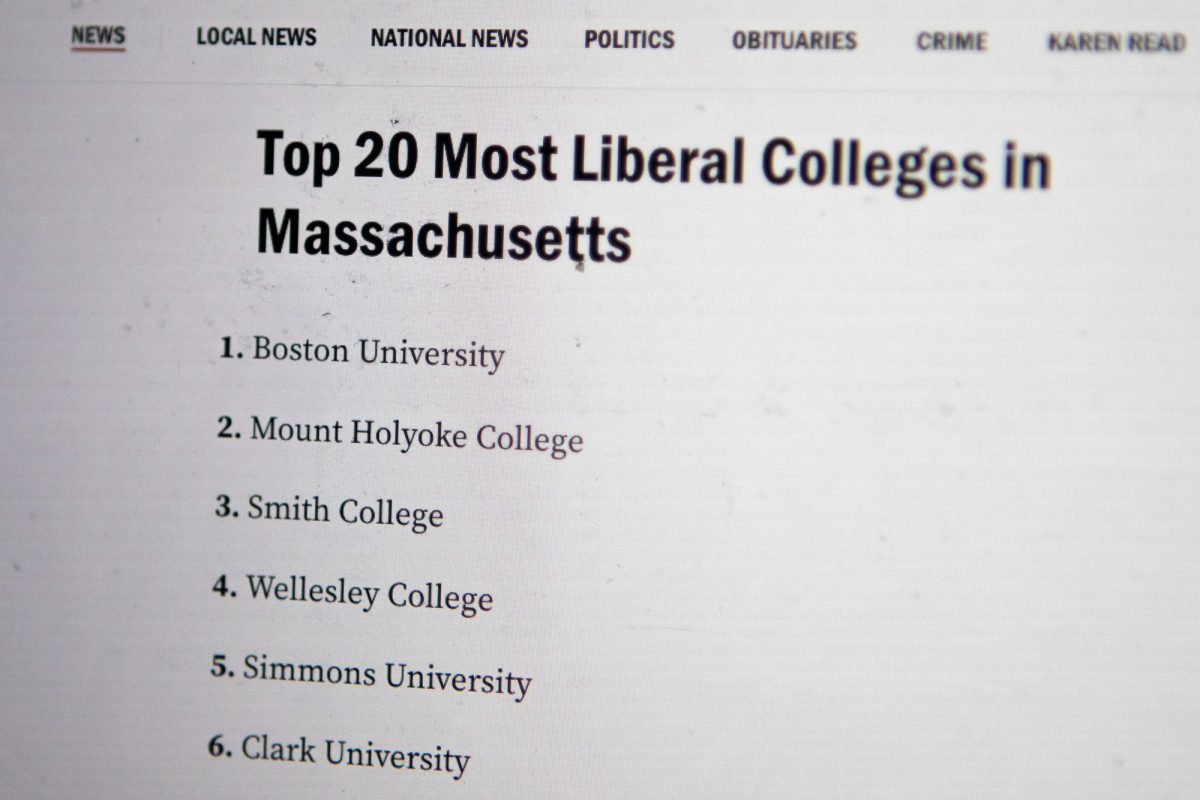

At this point in time, Boston University accepts students regardless of immigration status, according to a Daily Free Press article from 2013. This partially stems from an admissions officer from not being able to tell the difference between a documented and undocumented applicant, but because the status as an undocumented applicant may hinder the ability to pay for tuition. To clarify, this is not because all undocumented applicants are not as financially able as other applicants, but rather because they cannot apply for government aid, according to the Free Press article.

Two distinct arguments arise when considering the role of a university as a sanctuary for illegal immigrants, whether they chose this role in the United States or not. The first acknowledges that universities are not limitless pools of resources, able to shield anyone who asks, while the second acknowledges the role of a university to provide opportunity, blind of immigration status.

As above stated, a university has only a limited amount of resources regarding housing, financial aid and advising. Because an applicant cannot apply for federal aid, he or she will inevitably apply for need-based university financial aid. The question arises: If a legal citizen, who is equally qualified for a place at a theoretical BU, is up against an undocumented applicant for the lottery-based and puzzling enigma of financial aid, to whom should it be awarded? Though perhaps coming from a self-motivated perspective, the argument is valid and deserves examination.

Another question arises: When that student is theoretically shielded from deportation by a university, what opportunities are possible further down the line? In the United States currently, most jobs that require a college degree also require citizenship and are not willing to sponsor someone who is not a legal citizen. The job market is just too competitive, and many employers would rather save themselves the hassle of sponsorship and instead hire an equally qualified citizen.

Almost all universities, public or private, receive elements of government funding. Shielding students from potential deportation is a direct move against the government and could threaten this relationship. Would universities go to these lengths?

However, the second argument is just as valid. Most qualified applicants hoping to study or already studying at institutions of higher education did not actively make the decision to immigrate to the United States. Harvard student Villegas traveled with his family from Peru when he was 6 years old. What value does it do to “deport” these children who have grown up in the United States and only wish to continue their education? By allowing this potential deportation to happen, are universities merely pandering to an extremist view and allowing futures to be stalled indefinitely? Who is Trump to say who is worthy of an education and who is not?

Having undocumented students in a classroom provides not only diversity but perspectives that others simply do not have. Universities could view these students as an investment more than anything else, only enriching those perspectives.

Above anything else, the issue of deporting children who have been raised in the United States is a systemic issue. We often think of certain changes as “band-aid effects,” or those that do not address a larger issue. Providing sanctuary at a university is most definitely that, because after graduation, our nation is not such a kind place. The immigration system is broken in our country, something Trump recognizes, though is addressing in an extremely poor manner. Do we require reform? Most definitely, but expulsion is not the answer.