Based on countless social media reactions, many viewed 2016 as the year of the celebrity death.

Figureheads from all occupations and of all levels of notoriety were mourned across social media, traditional news outlets and niche groups of fans and followers. One group of graduate researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Media Lab, however, suggested that 2016 was not an anomaly, at least not for its high number of celebrity deaths.

In an empirical analysis of celebrity deaths, authors Cristian Candia-Castro Vallejos, Cristian Jara Figueroa and César A. Hidalgo collaborated at the Lab’s Macro Connections group to see whether the resounding sentiments regarding an excess of celebrity deaths were well-founded. For the sake of empirical integrity, several caveats were taken into account in the study, among them the definition of fame.

To determine which individuals were “famous,” the researchers consulted Pantheon, another product of the MIT Media Lab, concluding that an individual may be considered famous if his or her Wikipedia biography has been translated into at least 20 languages. While numerically accurate, using this definition of fame presented its own limitations.

“Wikipedia doesn’t represent general public behavior,” Candia-Castro Vallejos wrote in an email. “Instead, it represents to the people that edit Wikipedia: a group of people [enthusiastic about] the knowledge [and] with knowledge in digital media.”

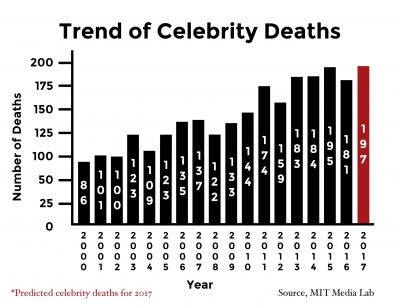

Population growth was also taken into account in the analysis of celebrity deaths, with the study noting that the number of celebrities is skyrocketing at a constant rate relative to the overall population. Considering this factor and examining celebrity deaths graphically, a linear representation shows that fewer died in 2016 than anticipated trends suggested.

The question remains: why did 2016’s celebrity deaths feel so overwhelming? The study suggested it was due to a rise in the role of communication technologies in everyday life, in addition to an increase in “mega-famous” deaths of individuals with Wikipedia biographies in more than 70 languages. In 2015, there were nine “mega-famous” individuals who passed away, whereas 2016 yielded the deaths of sixteen.

According to Candia-Castro Vallejos, this year — and, likely, those to come — was particularly notable due to innovations in communications technologies over the past few decades.

“Nowadays, we are suffering the death of our cultural referents who did their best work in sixties, seventies and eighties, where the television was their best ally in order to massify their works,” he said.

More modern innovations in communication technology following the rise of film and television are also contributing to an increased perception of celebrity deaths, especially among younger generations. Caitlin Schiffer, a junior in the Boston University College of Communication, wrote in an email that she has seen social media play a large role in the significant impact of celebrity deaths. That impact depends less on overall name recognition and more on personal connections and public contributions, Schiffer wrote.

“If a celebrity death means a lot to you, social media kind of just reinforces what you already feel about it,” Schiffer said. “There is more of an emotional impact if [people] were personally impacted by what [a famous individual] did.”

Samuel Baker, a senior in the BU College of Arts and Sciences, echoed Schiffer’s sentiments, saying that personal connection has a large influence on the interpreted severity of celebrity death in 2016.

“I am personally connected to a celebrity because I consider myself to be a fan of theirs,” Baker wrote in an email. “I believe that Facebook has changed how we perceive celebrity death. Social media permits the news of a celebrity death [to be] more dramatic and shocking.”

With emotion being a driving force in responses to celebrity deaths in 2016, Candia-Castro Vallejos said that social media exacerbated the emotional response of “mega-famous” deaths, contributing to the negative perception of the year.

“We tend to extrapolate from very little and biased samples, solely motivated by its emotional salience,” Candia-Castro Vallejos said. “Technologies shape our collective memory and thus shape our perception of the reality.”