Lives around the globe that were already impacted by the worsening of climate climate change have been further transformed by COVID-19. But what consequences does the pandemic have on climate-related equity and policy planning?

Local experts tackled pressing questions regarding this question at a webinar Friday hosted by the Boston University Institute for Sustainable Energy. The event was in partnership with the Northeast Clean Energy Council in its Energy of the Future series.

The webinar primarily focused on questions surrounding COVID-19’s influence on climate action urgency and the pandemic-induced shakeup in global markets, as well as potential growth in clean energy and manufacturing innovation in the United States.

The panel was moderated by Jacqueline Ashmore, the ISE executive director, and included a host of speakers. One of them was ISE Associate Director Cutler Cleveland.

Cleveland, who also serves as an Earth and Environment professor at BU, spoke about the commonalities between COVID-19 and climate change — specifically, their impact on lower-economic-class communities. He said during the panel that both the pandemic and extreme environmental shifts worsen health issues, economic losses and inequity in these areas.

“They both are invisible, frightening, deadly and exacerbated by global interconnections of people, information, goods, pollution and environmental degradation,” Cleveland said. “And both cause disproportionate negative impacts on some combination of people of color, low-income households with children, the elderly and people with low English proficiency.”

Jon Levy, an ISE faculty member and a professor in BU’s School of Public Health, presented his research, which displayed racial disparities between communities of color and the public health impact of COVID-19. Levy further explained the connection of these issues to housing inequities and environmental racism in Massachusetts.

“We’ve developed these data sets to look at factors that drive vulnerability to [COVID-19] across a number of different dimensions: social, environmental, housing and so forth.” Levy said during the talk. “One thing that makes elucidating these root causes more challenging is that many of these factors cluster geographically and demographically.”

Other panelists addressed the intersectionality of climate issues by discussing options and research to slow climate change as well as necessary policies to ensure the protection of vulnerable populations.

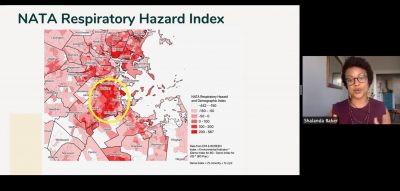

Shalanda Baker, a professor of law at Northeastern University, continued this discussion of environmental racism and justice, focusing specifically on the Boston area and beyond. Baker also said energy policy can combat public health crises in communities of color.

“I’ve been really interested in connecting the dots among race and that structural racism piece, COVID-19, as we’ve seen unfolding over the last six months, and energy justice,” Baker said. “I think there’s a role for energy policy within this broader reckoning that we are experiencing concerning race and the pandemic.”

Monica Huertas works as the co-coordinator of the Providence Racial and Environmental Justice Committee. During the panel, she addressed structural racism and its influence in zoning laws and school-to-prison pipelines, as well as environmental racism in communities of color.

“We can’t sugarcoat it: it’s obviously systematic racism, it’s obviously red-lining where unwanted chemicals and unwanted tanks and pollution were put with unwanted people,” Huertas said.

Arya Alizadeh, a second-year graduate student in BU’s Master of City Planning program, wrote in an email that issues in climate justice often factor into urban planning decisions, especially in states that have heavy environmental regulations.

“Planners and developers must take into account some of the environmental impacts of their projects,” Alizadeh wrote, “and, depending on local regulations and demands, sometimes create mitigation or redress for the environmental changes that occur.”

The impact of environmental racism has been shaping communities for centuries, but the coronavirus pandemic has placed a spotlight on these inequities. As policymakers begin to confront sustainability and climate action, Alizadeh wrote he believes changes are coming.

“The immediate impacts are slowly becoming clear,” Alizadeh wrote, “but from a city planning perspective we may not even realize the actual impacts of COVID for years if not decades to come.”