The days are getting longer, the flowers are blooming and the semester is finally winding down. The undeniable signs of spring have returned to Boston once again.

Everyone is enjoying soaking up the warmth and watching the streets come back to life, but to some, spring may not feel quite so satisfying this time around as it has in years past.

In celebration of Earth Day 2023, Boston University students should commit themselves toward becoming more educated about and invested in the ecosystem they will call home for at least four years of their lives.

The winter of 2022-2023 is tied with that of 2015-2016 for the warmest on record in Massachusetts history, with snowfall also being drastically below average levels. But milder winters mean more than less sledding and snowball fights.

Winter is the fastest warming season in New England, a region heating up faster than anywhere else in the county and almost in the world.

Since 1900, the average temperature in New England rose by 3.29 degrees Fahrenheit, compared to an average increase of approximately two degrees throughout the rest of the world.

This disproportionate increase has been driven primarily by warming in the Gulf of Maine, the body of water situated off New England’s coast, heating up faster than 99% of the world’s oceans.

Rapid warming throws both ecosystems and industries finely attuned to the changing of the seasons into disarray. Shifting migration patterns alter resource availability and disrupt food chains, and skyrocketing deer populations destroy other species’ natural habitats as invasive species creep further north.

Meanwhile, winter starting earlier and ending sooner hurts the ski resort industry and lower snowfall leads to drought during other seasons which affects agriculture and the intensity of New England’s famous fall foliage, further damaging the important tourism industry.

With the most to lose from rapid warming are New England’s many seaside communities. Warmer waters have triggered mass migrations and die-offs of fish, hollowing out the fishing industry upon which many New England towns have historically relied upon.

Moreover, sea levels in Massachusetts are rising three-to-four times faster than the global average — by far the greatest threat immediately facing the Boston area specifically.

Rising sea levels erode shorelines and damage coastal habitats, contaminate coastal drinking supplies with salt water and can cause billions of dollars worth of damage in infrastructure and private property.

In Boston, sea levels are predicted to rise as much over the next thirty years as they have over the past one hundred, endangering hundreds of thousands along the city’s more than 47 miles of coastline.

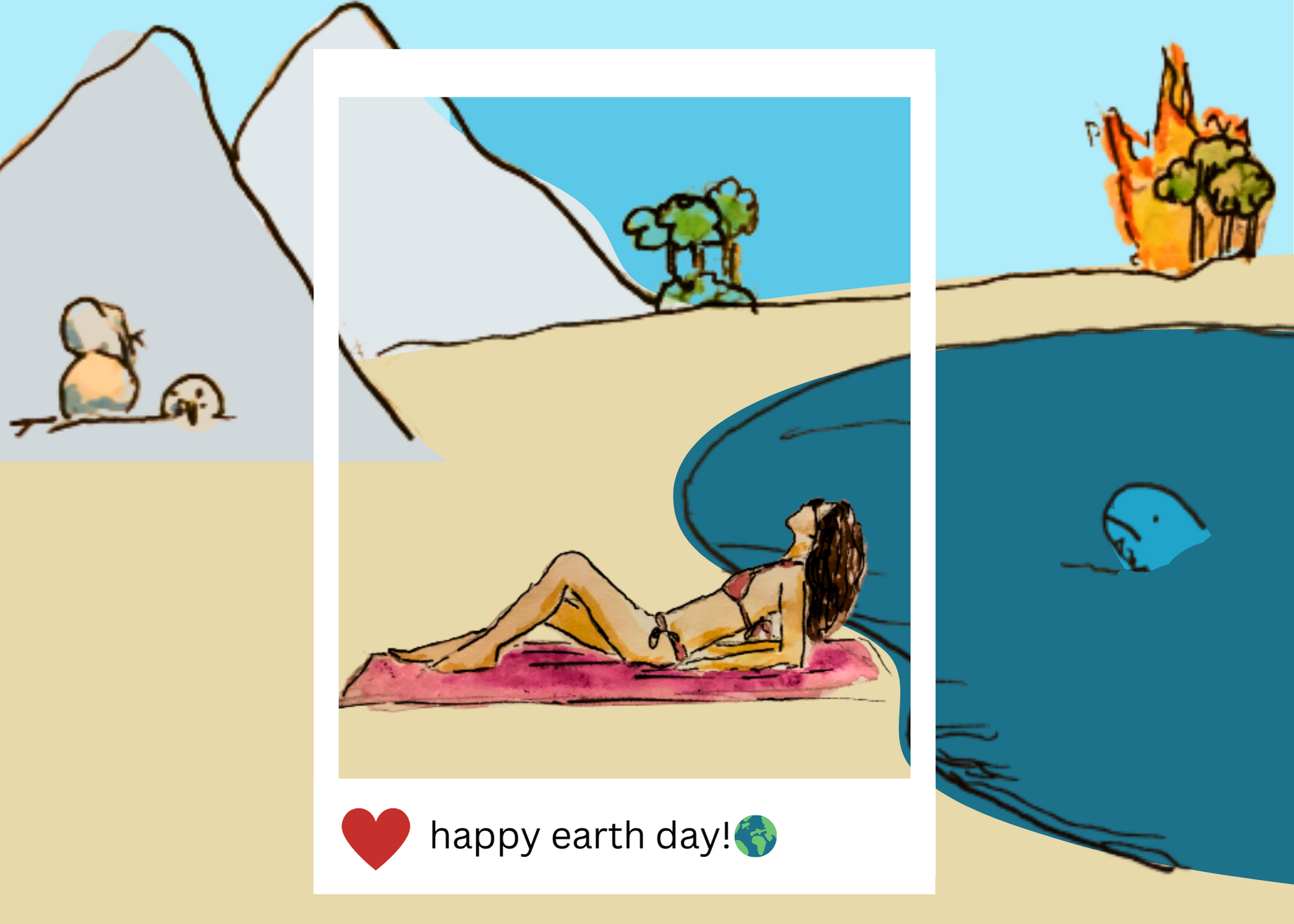

Around campus, if you’ve heard any conversation about this year’s unseasonably warm winter, it’s most likely been celebratory. Admittedly, sparing a layer of extra clothing when bundling up to walk between classes was a well-appreciated temporary convenience.

However, such conversations that celebrate unnervingly warm days and the suspicious lack of snow normalizes the signs indicative of the region Boston University calls home being uniquely vulnerable to the impending climate crisis.

It makes sense that such disconcerting seasonal trends may fall under the radar of many a BU student. Most of the BU student body is not from New England and may not be so keenly aware of what a normal amount of snow during the winter, rain during the summer, or lengths of spring and autumn are supposed to look like as would a native of the region.

As well, for the majority of BU students our time in Boston and New England is short and fleeting. Four short years isn’t a sufficient amount of time to gain a deep enough understanding and appreciation of an area in order to detect the subtle signs of climatological change.

The ephemeral nature of higher education leads to New England in general and Boston in particular, famous for their dense concentration of prestigious colleges and universities, being inhabited by hundreds of thousands of transients who contribute to the region’s carbon footprint while remaining uninvested in its long-term future.

Boston, Massachusetts and all of New England is a region rich with a natural beauty under more threat than virtually anywhere else in the country, but you wouldn’t know that though from only listening to the buzz around campus.

In the realm of climate change, the only level on which we can reasonably hope to enact meaningful change as individuals is locally. And doing so successfully requires being aware of and invested in the most pressing issues facing where you actually live, even if it’s only temporary.

This editorial was written by Opinion Editor Nathan Metcalf.