Wooden desks. A chalkboard. Chairs. Traces of pencil lead. Loose paper scattered around the room. Clean restrooms. This picture of an ideal classroom was left behind in the United States.

Instead, a roof balanced only on a handful of columns. At even the suggestion of rain, the dirt floor of the bare pavilion turned into a muddy disaster. In this Honduran “classroom,” walls didn’t even exist — much less anything that could be regularly found in a school.

Remi Gai, a College of Arts and Sciences junior, is out to change this image of Honduran schools through the Boston University chapter of the international organization Students Helping Honduras. This summer was Gai’s second service trip to the poverty-stricken country.

“I came back to Honduras a second time because I really enjoy their culture – how local people are down-to-earth and how life can be simple, enjoyable, without any modern materials,” he said.

His second trip was also the one that had the most impact on Gai. This summer, he met an 11-year-old orphan boy who had been living on the streets with his 9-year-old brother, hungry and without shelter.

“I couldn’t believe it because he seemed like any kids of his age, smiling all the time and innocent,” he said. “I could hardly imagine how many survival challenges they had to endure before they came to the SHH village. It made me realize how a community like SHH was important to orphans. It’s a place where they can be themselves, smiling, running around, playing – just being kids.”

Though Gai said his first trip was “random,” taken at the suggestion of a friend, he came back a second time because of the success of his first trip. He will probably return to Honduras for a third time this January for the BU chapter’s New Year trip, he said.

Although infrastructure is one of the problems keeping children out of school, Gai said the country is “ruled by gangs, who have more power than the government.” He said this discourages children from getting an education.

“90 percent of the population is affiliated with gangs or gang activities,” he said. “Children often join gangs at a very young age because they usually don’t have other choices in life. I remember that the week I went to Honduras, there was an article saying how a 13-year-old kid sliced an 11-year-old kid’s throat because he didn’t pay his 50 cents extortion money.”

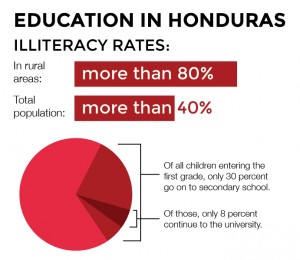

But there are further issues plaguing education in Honduras.

Madeleine Jacob, a CAS senior who attended a trip her freshman year, recalled there was only one teacher available to students when she was there. All kids, despite the difference in ages, were taught under the same roof.

“It was not an environment conducive to learning,” she said.

On her service trip, Jacob, along with about 30 other college students from all over the United States, helped build a school that would advance children’s education in the village of Villa Soleada. The new infrastructure included sanitary bathrooms plus four rooms for four different grades. New teachers were also hired.

“SHH has worked out a deal with the Honduran government saying if we build a school, some governmental agency will supply professors,” Jacob said. “So we’re getting infrastructure, employment and education — which is fantastic for these communities.”

Gai said one of the main objectives of SHH is to “end extreme poverty and violence in Honduras through education and youth empowerment.”

“Kids at SHH would get an education so that later on, they would have a choice of not joining gangs and get a proper job,” he said. “On a long term goal, gang influences and violence in Honduras will be reduced, with less future generations joining gangs.”

Jacob said she valued her trip for allowing her to see the issues facing the Honduran people firsthand.

“I could have given the money that I paid my flight with to the organization and that could have gone a lot farther than my unskilled construction work, but I went to Honduras, and now I have a better understanding of the Honduran people,” she said. “I have experienced their culture firsthand, and now they have a better understanding of American people. I think that was very important, and for that reason, I’m very happy I went.”