There are two things that will always define Boston: its vibrant history and its current character of strength and resilience. But what happens when the two don’t necessarily get along?

With Boston’s already skyrocketing popularity still rising, there is less and less room to fit all of its inhabitants. So, some developers and real estate agents are proposing, why not use the land currently taken up by old abandoned churches?

It makes sense on the surface: take a church that is no longer in use and either tear it down to build an apartment complex, or renovate it and make it into fancy condominiums. However, it’s a little bit deeper than that, especially when you consider this city’s history.

Those who live in the neighborhoods where this is being considered — South Boston and Roxbury, to name a couple — are not keen on the idea of these churches getting torn down to make way for wealthy people who, most likely, won’t even be from Boston. The churches symbolize faith, they say, and are important, even if they aren’t currently in use.

Take Boston developer Bruce Daniel, for example, who bought the property that the old, closed-down St. Augustine’s Church sits on in South Boston. He was met with very little support, especially from neighbors.

“Anybody who goes into a neighborhood and buys a church, without having some knowledge and sensitivity, they’re asking for trouble,” he told The Boston Globe. “It made more economic sense to knock it down, but we knew that wouldn’t happen … We weren’t surprised when the neighbors said no. There’s a lot of sentimental feeling about that building.”

So Daniel tried valiantly to reach a compromise with the residents, to little avail. The residents were not so enthused about choosing between no church and a church that is no longer a church.

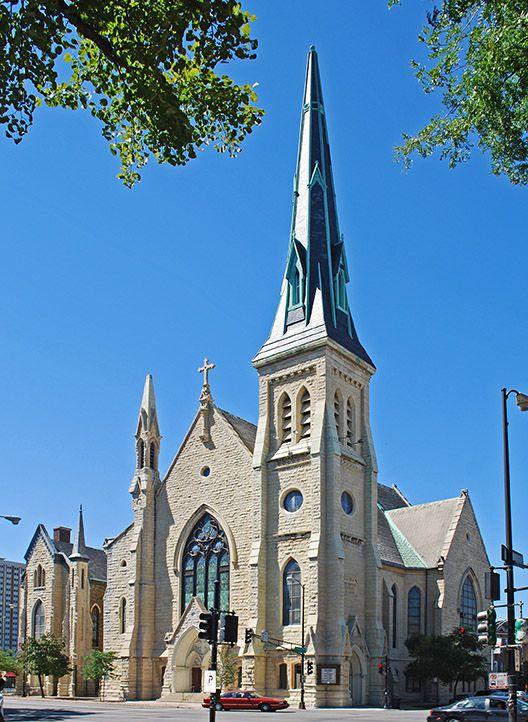

There are other areas where this church renovation is being considered more seriously, thanks to the construction of other big residential buildings in the area. In the South End, real estate and development company New Boston Ventures wants to convert an old church without changing its aesthetics. The only change would be a glass cube through the church’s stone roof, maybe for sunlight, maybe for ventilation. Modernity without sacrificing antiquity, but is it enough?

“A typical church plan is not particularly adaptable to housing because you need light and access to the outside,” said Graham Gund, an architect from Cambridge, to the Globe. “The walls are often quite thick, and inside you end up with a lot of space that’s hard to use.”

Clearly, this is not an ideal, and not a long-term solution for the lack of affordable housing in Boston. To be able to house a large amount of people, these churches would need to be really big and there would need to be a lot of them, neither of which are true right now. The housing that would result from renovating churches is most likely hip, trendy condominiums followed by gentrification, which helps no one but the wealthy, who already have homes.

Instead of buying up decaying churches for housing purposes, maybe the solution is to convert them into something else useful. What that “something else” is would be another conversation altogether, but churches were simply not made to house people, especially old churches. How much work would have to go into getting an old church up to safety codes? How much money would have to go into making it livable? Adding plumbing and kitchens to every new apartment?

Maybe people would pay for all of that that just to get the chance to live in an old, probably beautiful and historic church. But the people who can’t find housing are the people who can’t afford to live in an old, probably beautiful and historic church.

But on the flip side, what else would be done with them? The Boston University dormitory 575 Commonwealth Ave., commonly nicknamed HoJo, used to be a hotel — “HoJo” comes from Howard Johnson Co., the company that BU leased the building out to for redesign. Residents don’t like it now, but what happens in 30 years when the church is totally falling apart?

If both problems — the fact that there are lots of abandoned churches and the fact that there is a housing shortage — could be fixed by just one solution, that would be great. But real estate and development companies might be trying to kill two totally unrelated birds with one opportunistic stone. We need to do something about both problems, but this just isn’t it.