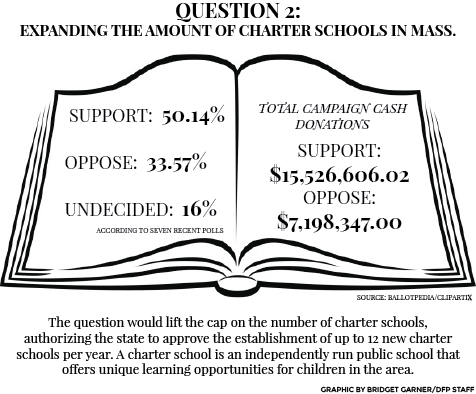

This is the second in a four-part series exploring the Massachusetts Ballot Questions, which will be voted on this November.

Massachusetts Ballot Question 2, if passed, would lift the cap on the number of charter schools in the Commonwealth, authorizing the state board of education to approve the establishment of up to 12 new charter schools per year as well as the expansion of existing schools, according to Attorney General Maura Healey’s office.

Great Schools Massachusetts, the organization leading the support for Question 2, is a coalition of parents, stakeholders and people in the education community in support of Question 2, according to spokesperson Eileen O’Connor.

O’Connor explained that charter schools can help urban communities that are presently at an educational disadvantage.

“[Charter schools] have proven they can close the achievement gap,” O’Connor said. “They have longer school days, longer school years and are producing incredible academic outcomes for their children, particularly in our urban communities where children are desperate for an alternative to their failing schools.”

Katarina Rusinas, the digital director for Save Our Public Schools, a grassroots campaign organized in opposition of Question 2, disagrees with this claim, stating that the current charter school system discriminates against certain students.

“It’s hurting our most in need students,” Rusinas said. “Oftentimes kids of color or kids with disabilities are getting pushed out of charter schools and pushed back to public schools who then don’t have the resources and the funding to help them in the way that they need.”

Rusinas also said funding is an issue for public schools, and that the ballot measure would have a negative financial impact on public schools in the state.

“Charter schools currently take about 450 million [dollars] a year from our public schools and if the cap was lifted, it’s estimated to be an extra 100 million a year,” Rusinas said. “In six years, that turns into a billion dollars and our public schools just cannot afford that.”

However, according to O’Connor, there is mounting evidence that the growth of charter schools in Massachusetts would help public schools financially.

“Charter schools have actually resulted in more funding for public education,” O’Connor said. “They have had the impact of increasing per-pupil spending across the Commonwealth, so the notion that charter schools drain districts of funding is simply not true.”

Additionally, there are measures in place to soften the legislation’s impact on public schools, according to O’Connor. For instance, a funding arrangement would reimburse districts over a period of six years after they’ve lost a child to a charter school, O’Connor explained.

“We’re not going to go where charter schools aren’t wanted,” O’Connor said. “This is very much about bringing these options to communities where there is demand for alternatives to public education.”

Despite their opposing views, both organizations are dedicated to improving education institutions in Massachusetts.

“It’s everything,” Rusinas said of the education system. “It affects just about everyone in the state, and in 20, 30 years, the students that we’re teaching now are going to be running the state.”