Ranked-choice voting may become a reality for Massachusetts residents in the coming years.

The Ranked-Choice Voting Initiative will be an item on the Nov. 3 ballot in the Commonwealth this year, after a campaign that garnered nearly 120,000 signatures was deemed valid by the Massachusetts Secretary of State.

If voters approve the initiative, RCV will be implemented in primary and general elections for state executive officials, state legislators, federal congressional seats and certain county offices starting in 2022.

The current voting system in Massachusetts, plurality voting, requires voters to choose one top-choice candidate. This creates a system in which two popular candidates who share a similar voter base could split the vote, allowing a less popular candidate to ultimately win an election.

Ashley Houghton, director of communications at FairVote, a nonpartisan organization focused on electoral reform, wrote in an email that RCV will allow voters to vote for their favorite candidates rather than strategically cast their ballot for someone they assume will have a higher chance of winning.

“Massachusetts voters will be able to make choices based on who they believe would be best for the job of Governor or Senator or Member of Congress (as an example),” Houghton wrote, “without worrying about ‘spoiler’ candidates or making careful calculations about electability.”

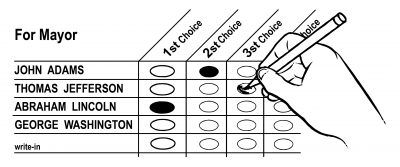

In RCV, a candidate must receive more than 50 percent of the first-preference vote to win outright.

If no candidate receives a majority, the candidate with the least amount of first-preference votes is eliminated from the ballot. Voters whose first-pick candidate is eliminated will now have their second-preference choices be counted as their first-preference choices.

This method repeats until one candidate gains the majority vote.

Michael Meehan, a senior advisor to Voter Choice for Massachusetts, the campaign that spearheaded the push to put RCV on the 2020 ballot, said this form of voting will mean a move away from political polarization and complacency.

“People on the left and the right settle,” Meehan said. “If you rank-choice your vote, you would not have to pick between the lesser of two evils.”

Kristina Mensik, assistant director of Common Cause Massachusetts, a nonpartisan organization advocating for electoral reform, said RCV would shift politicians’ attention from competition to policy.

“I think that the byproduct of that is you have candidates who focus on the actual policy preferences of their voters,” Mensik said. “Which hopefully means more effective policymakers and then ultimately a greater faith in our democratic process and hopefully more participation.”

Paul Craney, a spokesperson for Massachusetts Fiscal Alliance, a nonpartisan nonprofit promoting economic responsibility, is an opponent of RCV. He said such a system is too complex.

“You’re putting a very high amount of pressure on the voter to make all these complicated decisions when they go to vote,” Craney said, “and the last thing you really want to do is make it too hard for the voters.”

But Craney said he does not believe RCV should be eliminated across the board.

“It works well for Cambridge because they’ve done it for such a long time. People there are used to it,” Craney said. “But to mandate it across the state, it’s going to create a tremendous confusion, especially early on.”

If the initiative passes, Massachusetts would become the second U.S. state to adopt the system for the election of all state executive and legislative officials — after Maine, which implemented this in 2018.

If RCV does not receive enough support in the November election, the plurality of the current voting system will remain intact.

Other states such as Utah, Virginia, Kansas and California have also demonstrated increased support for this method of voting, Houghton wrote.

“Massachusetts has always been a leader, but they could truly set the standard for other states,” Houghton wrote. “If Massachusettans starts to use ranked choice voting, it’ll be a sign to other states that they can implement voting reforms that give their voters greater voice and greater choices.”

Andy Anderson • Jul 20, 2020 at 10:55 am

Re Paul Craney’s comment “You’re putting a very high amount of pressure on the voter to make all these complicated decisions when they go to vote”, the facts indicate the opposite. Ranking is a natural process for people, we do it all of the time when grocery shopping, etc.

Surveys of the electorate where RCV is being used for the first time, such as the state of Maine and the cities of Minneapolis and Santa Fe, demonstrate that the majority of voters like Ranked Choice Voting and don’t find it “hard” (see https://www.fairvote.org ). It’s simply a matter of educating them about their new capability, that voting can now be more than just pick one and they can rank some or all of the candidates on the ballot. And the initiative requires that “the state secretary shall conduct a voter education campaign to familiarize voters with ranked-choice voting.” I expect that non-profit organizations that engage in voter education will also be active, such as the League of Women Voters, another supporter of ranked choice voting.

Ideally voters become familiar with all of the candidates on the ballot before they even make their first choice, and after that it’s just repeating the process with the remainder — not at all “confusing”. It’s also important to realize that even if a voter does choose just one candidate, Ranked Choice Voting is still to their benefit — their vote continues in every round of voting as long as that candidate has not been eliminated, possibly to the final round and helping determine the winner.

You can read the full text of the initiative here: https://voterchoice2020.org/ballot-text/