Boston, Massachusetts is known best for its host of iconic attractions such as landmark sites like the Paul Revere House and the Freedom Trail, as well as its all-star sports teams including the notable Red Sox and New England Patriots. There’s a plethora of reasons for people to visit, fall in love and settle down in the great city — but soaring rent and living costs certainly don’t fit this picture-perfect image.

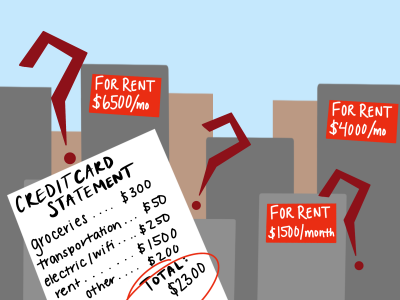

The Zumper National Rent report’s most recent analysis on Nov. 22, 2022, concluded that Boston and San Francisco are now tied for the most expensive rents, falling just shortly behind New York. While this is an issue that, years ago, mainly would have impacted new graduates looking for jobs in the city, the gravity of the situation is now being felt by college students in the surrounding area who are looking to get the most for their dollar’s worth.

College tuition alone is expensive, as the annual fee for Boston University students’ attendance is estimated at an astonishing $82,760 for the 2022/2023 academic year.

When considering the challenge that comes with moving out of your childhood home, many students opt for University provided housing and dining options. This quick selection on the BU student link seems most convenient, despite the costly outlines, but in recent years more and more students seem to be branching out to other off-campus housing options. Still, the main question at hand remains: which is the better option for struggling students?

On the surface, the argument infers one place to live is better than the other, but that sentiment seems to ignore the reality of the situation.

In the past five years, the cost of board at Boston University has increased by 2.7% for nearly all residences. Despite the escalation in price, most dormitories do not come equipped with kitchens, making a dining hall subscription a mandatory cost. Further, other buildings, such as Warren Towers, are not privy to built-in air conditioning units to get students through the warmer months, and thus, the price of a fan must also be factored into the total living cost.

Conversely, moving off campus doesn’t seem to hold a much greater fate, with skyrocketing rents and housing shortages limiting options. The Zumper reports detailed that current Massachusetts zoning laws tend to favor single-family homes, driving median apartment rent costs up to luxury prices.

The central issue to the overarching problem is how divided the argument has become.

Many see students who choose to live off-campus as the reason for increasing board fees within the University due to the loss of student residence charges. As of the fall of 2021, an average of 37% of all undergraduate students lived off-campus, and while the numbers have not been run recently, it is thought that the total percentage has increased.

The “studentification” as observed by surrounding landlords, has been used to argue that the influx of students moving to off-campus housing locations, such as Allston, have been the cause behind the spiking rent costs.

In light of the poor living conditions found in some dorms, or the increasing housing shortage across campus, some students remain forcibly loyal to institution housing due to scholarships.

Whether the money is coming from BU, or another outside organization, students who have their board covered are unable to move off-campus, unless they can afford a pricey out-of-pocket housing fee. Even in this scenario, a range of hidden residence charges still hurt students’ wallets such as appliance rental, laundry load charges, on-campus insurance and dining plans.

It seems that all in all, students really can’t win. While it has become a societal norm for college kids to leave their institution with mounting debt, the day-to-day cost of just existing within this major city is slowly becoming unattainable.

The crisis extends far beyond housing — bi-weekly grocery trips have been hit by inflated prices, mandatory textbooks soar in cost, MBTA fares grow annually —students are being sucked dry.

Perhaps the issue lies not where students choose to live, but rather in the basic principle of supply and demand. If we do not tackle the housing crisis from its roots in Boston’s long and growing history of gentrification and capitalist enterprises, living in a region that is rich in history, fine arts and opportunity will soon be impossible.

Written by Opinion Editor Analise Bruno.