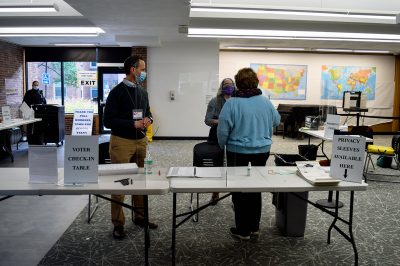

A coalition of voters’ rights advocacy groups helped fill all poll worker positions in Massachusetts Tuesday, following concerns the pandemic would exacerbate poll worker shortages typically prevalent in election years.

More than 566 poll workers assisted voters at Boston’s 255 voting precincts, according to an Election Department press release. These workers offered help in English, Spanish and Chinese, among other languages heavily spoken in the city, such as Vietnamese, Haitian Creole and Cape Verdean Creole.

Kristina Mensik, assistant director of Common Cause Massachusetts, said poll workers ensure voters have a positive experience. This could, in turn, determine whether residents continue to vote in the future.

“Voting is a habit,” Mensik said. “You are more likely to participate if you have a good experience at the polls.”

Poll workers ensure voters receive the correct ballots and that these ballots are fed properly into the ballot-reading machine, Mensik said.

Advocates noticed a “severe” shortage of poll workers during presidential primaries this spring in states such as Wisconsin and Georgia, Mensik said. Poll workers tend to be older, meaning they are in a higher-risk group for COVID-19 and could not safely volunteer.

“In response to that challenge,” Mensik said, “a number of groups really coalesced around that task of adequately staffing the polls.”

But filling a dearth of poll workers is not a challenge unique to 2020. In 2016, nearly 65 percent of jurisdictions that responded to a U.S. Election Assistance Commission survey reported it was “very” or “somewhat” difficult to find enough poll workers for the general election.

Shortages on Election Day could leave many polling places closed across the country, Mensik said, or cause a “whole slate of problems,” including lengthy lines at polling stations and failure to process ballots on time.

Alex Psilakis, policy and communications manager for MassVOTE, which partnered with Common Cause on poll-worker Utah recruitment, said these problems would have disproportionately harmed voters in communities of color and lower-income neighborhoods.

Boston-area advocacy organizations regularly send volunteers to protect voters’ rights at the polls, where Psilakis said they watch for voter intimidation, unfair ID requirements and language access issues.

But Mensik said the organization realized this summer the mission wouldn’t be possible without an adequate number of poll workers. In the context of the pandemic, election officials also found themselves rushing to implement changes to the process within a “very short” window of time.

To alleviate these issues, Common Cause recruited and trained about 200 poll workers, Mensik said, adding she feels many people also decided to volunteer as poll workers on their own.

“By September, we had some folks telling us, ‘Honestly, don’t send us any more names,’ because they had seen such a surge,” Mensik said.

Massachusetts waived this year its requirement that poll workers can serve only in the municipality they are registered to vote in, Mensik said. This allowed municipalities with a surplus of workers to send help to areas in need of more.

Psilakis said poll workers are trained to deal with confrontational voters, but that what is considered “confrontational” has become murkier as societal attitudes evolved over recent years.

“Four to eight years ago, a confrontational voter would be somebody that wears a shirt that has a specific party on it or a specific candidate,” Psilakis said, “because you’re not supposed to wear any campaign-related materials inside a polling place.”

This year, poll workers sanitized polling stations and distributed personal protection equipment to voters, Psilakis said. The City also provided poll workers with masks, face shields, gloves, hand sanitizer and disinfectant, according to the Election Department press release.

Mensik said people should start seeing working at the polls as part of their “civic hygiene,” a term she recalls hearing from a leading elections advocate in Boston.

“In my experience,” Mensik said, “it’s really hard to work at the polls and then walk away and not be a little bit more invested in the outcome of the election that you just helped facilitate.”

Working at the polls is an opportunity to learn about the way elections work and to better understand the importance of making them accessible, she added.

Despite the Commonwealth’s success in meeting this year’s demand for poll workers, however, Psilakis said shortages may continue to pose a problem in the future.

“The sad fact is that it takes literally a pandemic to really get people motivated and energized,” Psilakis said. “[We’re] trying to encourage folks and tell them, ‘Maybe keep coming every year, because these issues are at stake.’”