In the windowsill, a flash of fabric catches your eye. You’ve been needing a new sweater, and cold weather is settling in fast, bringing a scramble to find insulating clothing lest you catch a cold during the pandemic. The sweater is made of cheap fabric, but that’s to be expected at Primark. The price is affordable, so as a college student, it’s a steal.

Knowing that laborers for fast fashion brands such as Primark are often mistreated and underpaid, and knowing fast fashion is unsustainable, would you still buy that sweater? Herein lies the moral dilemma. Fast fashion, defined as the use of cheap materials and labor to quickly mass-produce trendy clothing, is just one of consumerism’s many problems.

If you were a conscious consumer, you would recognize the negative impact of buying the sweater, probably not buy the sweater in favor of a more sustainable option and maybe boycott brands such as Primark altogether.

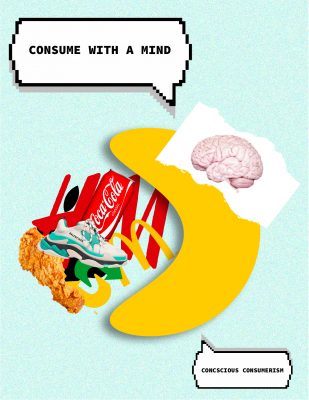

Conscious consumerism is a movement that promotes being aware of what you buy and financially supporting brands that align with your values whenever possible. The movement has been gaining momentum recently, especially in younger circles. It is often thought of as ethical consumerism because it also promotes boycotting unethical companies and finding ethical alternatives.

But “ethical consumerism” is a misnomer. The concept of conscious consumerism does not equate to ethical consumption, because it is not absolute. There is no ethical consumption under capitalism.

Therefore, just as living zero-waste is impossible, so, too, is being completely consequence-free with one’s purchases. And it’s not something to feel bad about.

Try as you might, it is incredibly difficult to align morality with reality. Though it is pertinent to support small businesses and shop as sustainably as you can, I, for one, still financially support companies that I don’t ethically agree with, such as Amazon.

The show “The Good Place” explains this dilemma well. In the third season’s 10th episode, “The Book of Dougs,” the characters examine two case studies: Douglass Wynegar from 1534 and Doug Ewing from 2009.

In the show, humans are sorted to a Good Place and a Bad Place based on a points system. Wynegar earned 145 points for giving his grandmother roses. Even though Ewing did the same for his grandmother 500 years later, he actually lost points.

“Why?” one of the characters, Michael, said. “Because he ordered the roses using a cell phone that was made in a sweatshop, the flowers were grown with toxic pesticides, picked by exploited migrant workers, delivered from thousands of miles away, which created a massive carbon footprint, and his money went to a billionaire racist CEO who sends his female employees pictures of his genitals.”

Michael went on to say the world gets more complicated every day, which makes it harder to be a good person. Indeed, in our modern, capitalistic society, every action has negative consequences — intended or unintended. We are all unwittingly contributing to and enabling unethical practices, just like poor Doug.

Talk about overwhelming. The thought of trying to stem the consequences of your purchases from all different fronts — groceries, takeout, necessities, clothing, medication, makeup and so on — is enough to deter you from even trying. It seems futile, doesn’t it? Plus, it’s sobering to realize that being able to switch to more sustainable products is a privilege in itself.

But this is exactly why conscious consumerism cannot be equated with ethical consumption. There is no way one person can do all that, and they shouldn’t be expected to. The most important aspect of conscious consumerism is being aware of your consumer footprint.

Separating conscious and ethical consumption is useful because it doesn’t create a binary between good and bad. This also eliminates the narrative that the average individual should take on the burden of capitalism’s effects. Rather, the responsibility to actualize change lies on mass corporations and billionaires.

In fact, the flexibility of conscious consumerism allows it to be more inclusive. You don’t have to reach a threshold of sacrifice to be considered a conscious consumer. Regardless of socio-economic status or access to sustainable brands, everyone can contribute by doing the best they can to be aware and educate their peers.

We can do our research and vote with our wallet when possible, but we can also cut ourselves some slack. We shouldn’t beat ourselves up if we don’t manage to change our entire lifestyle overnight or if we can’t afford to buy high-end, sustainable and ethical products.

Lastly, while our individual choices do make a difference, we should also remember to apply pressure to large corporations that actively benefit from unsavory business models and the officials who have the power to change that. Send companies emails and letters through the postal service. Show up at town halls and get involved with legislation and protests when you can.